By Alexis Voisard, MA Student in English, 2022-23 Rare Books Graduate Assistant

Working with the rare book collection this year has been a delightful experience in my graduate program. I’ve done deep research dives into the Ohioana collection to uncover diverse perspectives crafting historical narratives about Athens and the Travel collection to find illustrations and images to share on the @AldenLibrary Instagram.

My latest deep dive has led me to the Edmund Blunden Collection, the largest personal library we have in the rare book collection. With such a large collection, I’ve roamed the shelves to observe the different genres and topics he collected, as well as archival records about how the collection was acquired. Both sites of information have helped me discover answers to questions I’ve had about rare book collectors like Edmund Blunden. What can we learn about a collector from the books they collect? How do collectors engage with their books? What do collectors leave behind in their books?

I invite you to check out the exhibit highlighting a few of the remarkable women authors that Blunden collected, a context that narrows the answers to these questions in unique ways that connect to evidence from archival information documenting Blunden’s collecting processes and interests. See these featured books in person on the 5th floor of Alden Library in a display case in the Dean’s Suite. It will be on view through the end of the spring semester. Continue reading to learn more about some of the women in the Blunden Collection.

Fanny Burney & the Writing Process

Blunden collected several works by Madame Ol’ Arblay, better known by her maiden name, Fanny Burney, including Evelina (1911). Blunden likely apreciated her writing for her keen observations of British culture and society. She was involved in royal social circles when she was presented to Queen Charlotte and King George II in 1785. Her journals from the time reflect an ear for gossip. She published Evelina anonymously at age 26, and with the book reportedly taking London by storm, her fame bears resemblance to the fictional Lady Whistledown of Bridgerton, a Netflix depiction of royal courting culture. Burney’s diary entries and letters are well represented in the Blunden Collection.

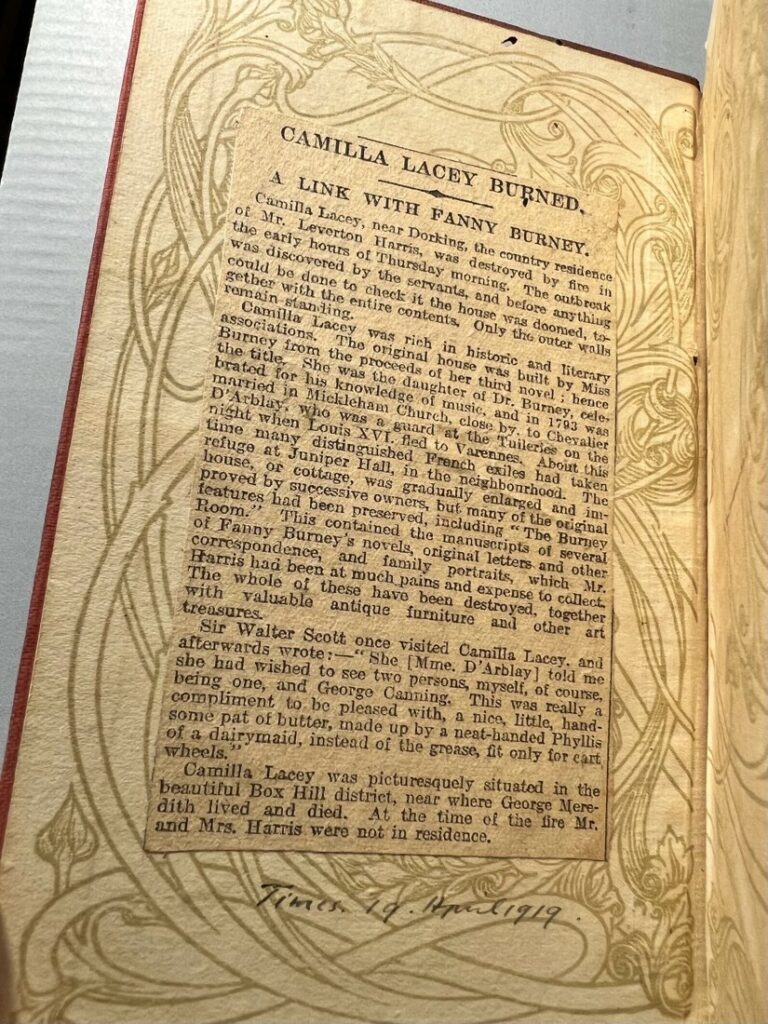

Blunden liked to attach relevant newspaper clippings in his books that related to authors and events taking place in the books he collected. In one of his copies of Evelina, he glued a newspaper clipping to the inside cover from The Times, dated April 19, 1919, titled “Camilla Lacey Burned: A Link with Fanny Burney,” which tells of the history of Burney’s influence on a house that burned down, including the Burney Room, which held manuscripts of several Burney novels, original letters, and family portraits, sadly all destroyed in the fire.

From The Early Diary of Frances Burney, 1768-1778, readers can learn more about her writing process with Evelina and what royal court life was like. She certainly downplayed her success as a writer in her diary entries, including this entry about sharing early manuscript drafts of Evelina:

“[while I was taking leave, I was so much penetrated by my dear father’s kind parting embrace,] that in the fullness of my heart [I could not forbear telling him, that I had sent a manuscript to Mr. Lowndes; earnestly, however, beseeching him never to divulge it, nor to demand a sight of such trash as I could scribble…but when I told my dear father, I never [wished or] intended, [that even] he [himself] should see my essay, he forbore to ask me its name, or make any enquireies [sic]. I believe he is not sorry to be saved the giving me the pain of his criticism. He made no sort of objection to my having my own way in total secrecy and silence to all the world.”

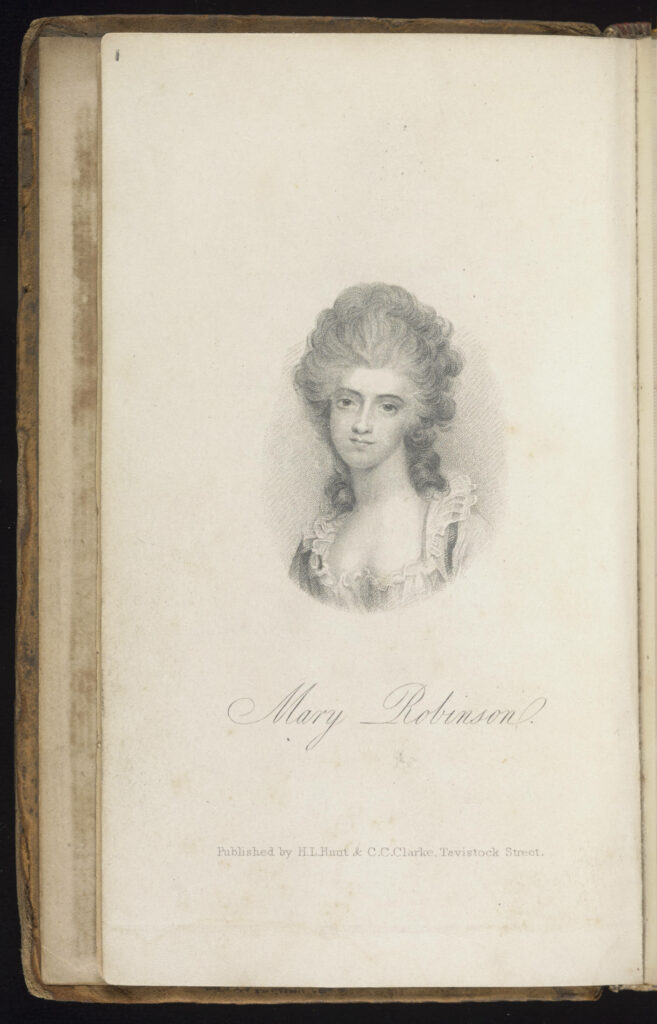

Mary Robinson & Life in England

From Mary Robinson’s works we can observe the kinds of writing that Blunden collected to learn more about British life in the 18th and 19th centuries. Mrs. Robinson herself was quite the character in British history and had unique experiences and connections with British royalty and theatre. She completed a wide range of writing projects, including 6 novels, 2 plays, a feminist treatise, as well as an incomplete autobiographical manuscript at the time of her death. These writings provided a necessary source of income since her husband, Thomas Robinson, was in prison for debt after living beyond their means in London. She was also a Shakespeare actor. Her 1799 performance as Perdita in David Garrick’s adaptation of Shakespeare’s The Winter Tale captured the attention of the future King George IV and led to a short affair that received public attention. This passage from her memoir describes her reaction to receiving this attention after her performance:

“I then experienced, for the first time in my life, a gratification which language could not utter. I heard one of the most distinguished geniuses of the age honour me with partial approbation: a new sensation seemed to awake in my bosom: I felt that emulation which the soul delights to encourage, where the attainment of fame will be pleasing to an esteemed object. I had till that period known no impulse beyond that of friendship; I had been an example of conjugal fidelity; but I had never known the perils to which the feeling heart is subjected in an union of regard wholly uninfluenced by the affections of the soul.”

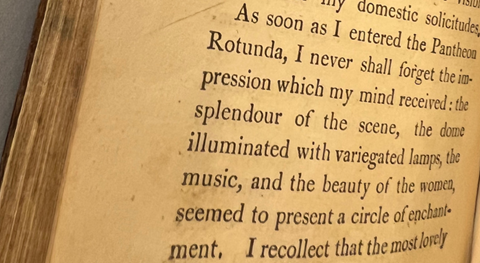

Blunden appreciated collecting books that shared interesting perspectives about British life, and Robinson’s connections to the Royal family and cultural influences made her writing a perfect fit. Blunden collected all four volumes of Memoirs of the Late Mrs. Robinson (1801) that originate from Robinson’s incomplete autobiographical manuscript and included several annotations illustrating how he engaged with Robinson’s writing. For example, when Robinson describes a connection to one of her homes with a celebrity named Mr. Thomas Worlidge, Blunden recognizes the latter with a note at the bottom of the page, “a collection of his works is shown at Peterborough Museum.” Blunden also marks several passages of interest with a brief pencil stroke; one of which is a rich description of Robinson’s encounter with the Pantheon Rotunda:

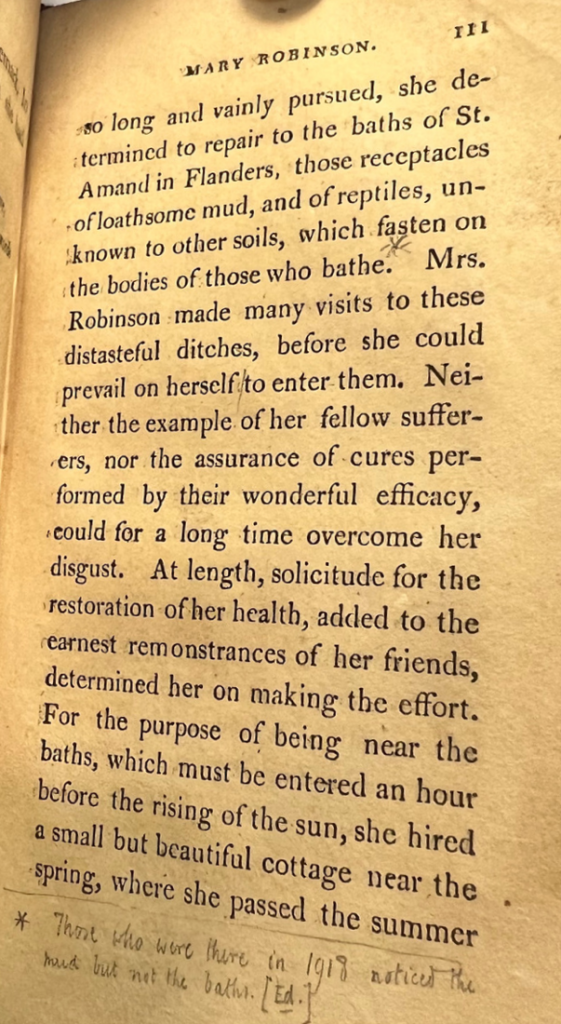

In another passage where Robinson reflects on theatre performing seasons with the late Mr. John Henderson, Blunden wrote: “Henderson was among the numerous company who wrote a poem to the “beauteous Robinson.” Blunden also finds locations that he personally visited during his service in World War I, including a sobering note about the baths of St. Amand in Flanders, reflecting “those who were there in 1918 noticed the mud but not the baths.”

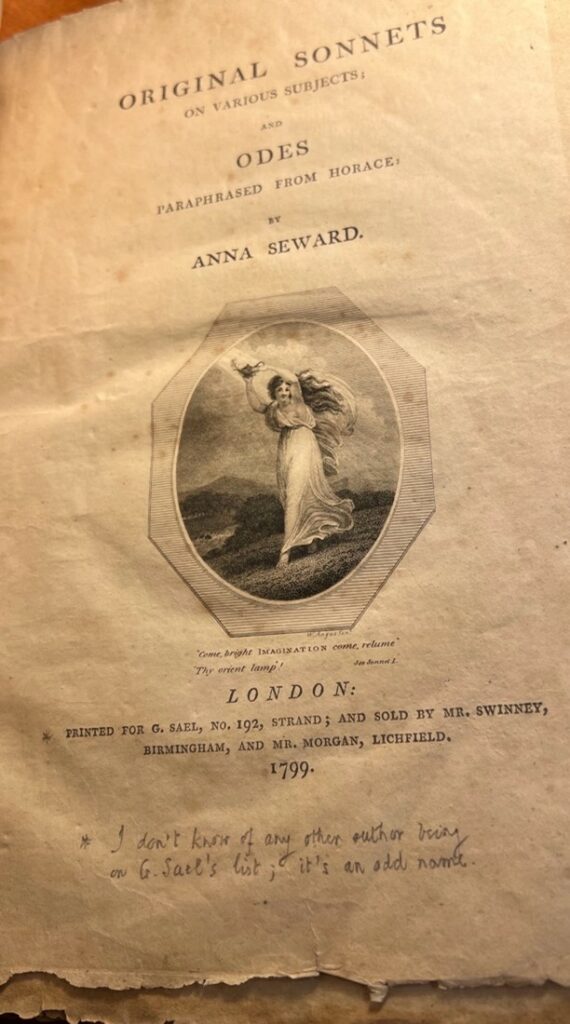

Anna Seward & Literary Critique

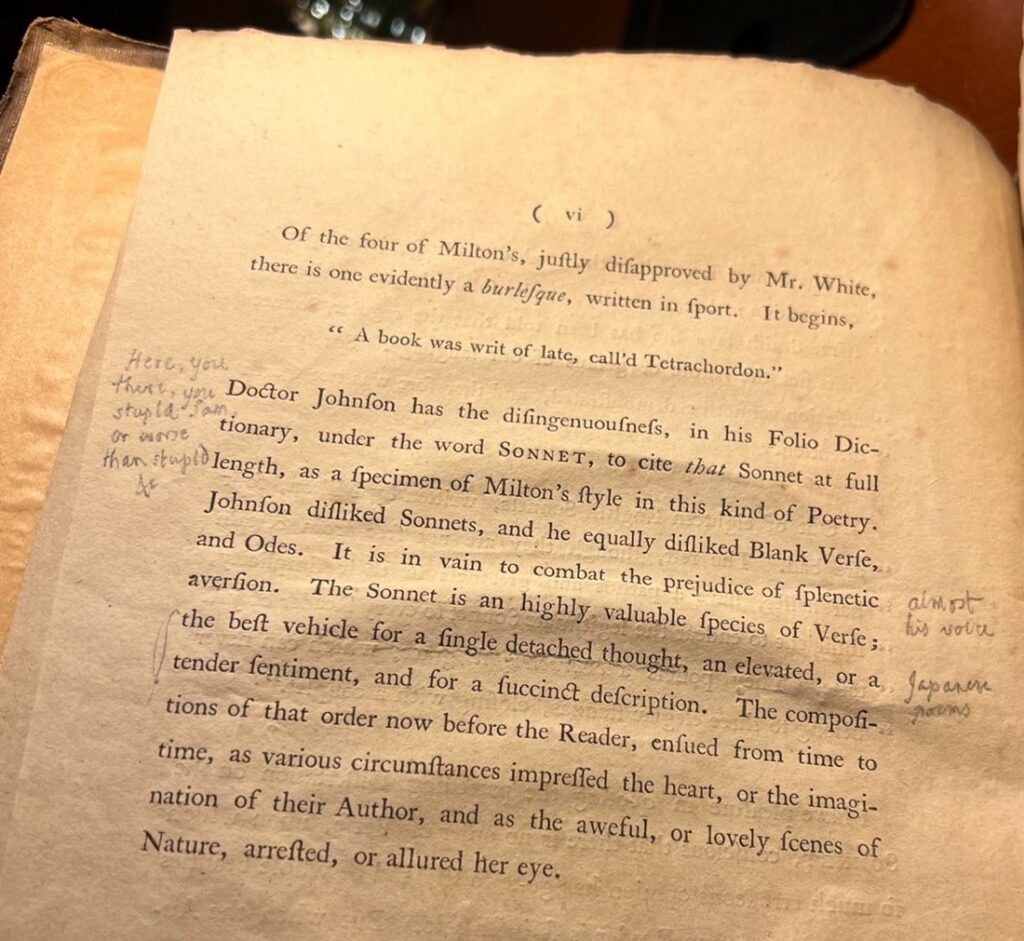

Blunden loved to mark his books with notes and reactions to the text. One of my favorite books to browse for these additions is Anna Seward’s Original Sonnets on Various Subjects (1799). There are a wide range of marginalia that represent the kinds of notes Blunden left in the margins. Blunden notes on the title page, “I don’t know of any other author being on G. Sael’s list; it’s an odd name,” a note referring to the publisher, with G. Sael appearing to be new to Blunden’s collection.

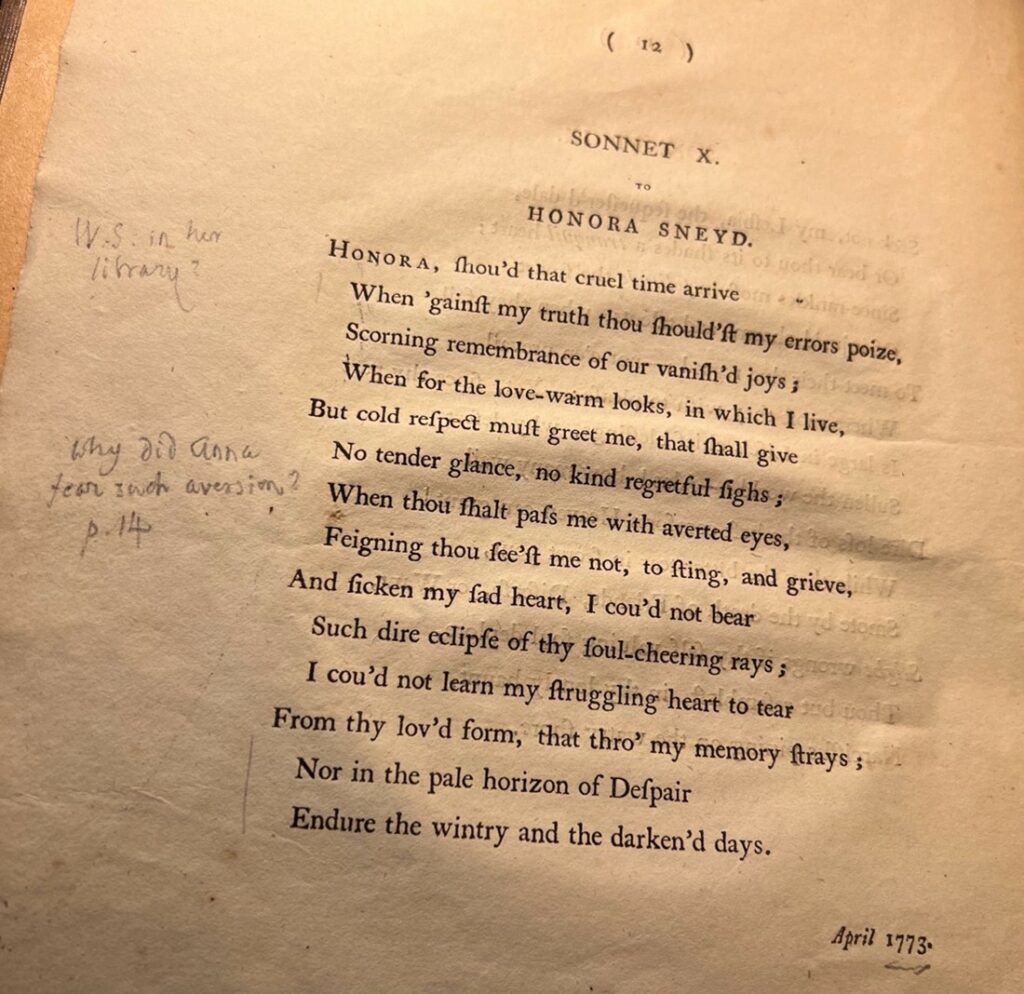

A poet and critic himself, Blunden was not afraid to write down his thoughts while engaging with poetry. One comment stands out on page 6 where Blunden writes “Here, you there, you stupid Sam, or worse than stupid” in reaction to a passage that discusses Doctor Johnson’s dislike of sonnets and blank verse poetry. He also comments, “Japanese poems,” a connection that reminds us of Blunden’s interest in Japanese literature and time spent teaching in Japan. He also writes questions that arise from reading poetry, such as when he asks, “Why did Anna fear such aversion?” This question in particular reflects current research about Anna’s possible connections with queer identity, where this sonnet evokes feelings of forbidden love toward her foster sister Honora Sneyd. Read more about modern, scholarly conversations about Seward’s writing and connections with queer relations in a 2012 article (*note that an Ohio University login is required for access) in Gender Forum.

Mary Russell Mitford & Nature Writing

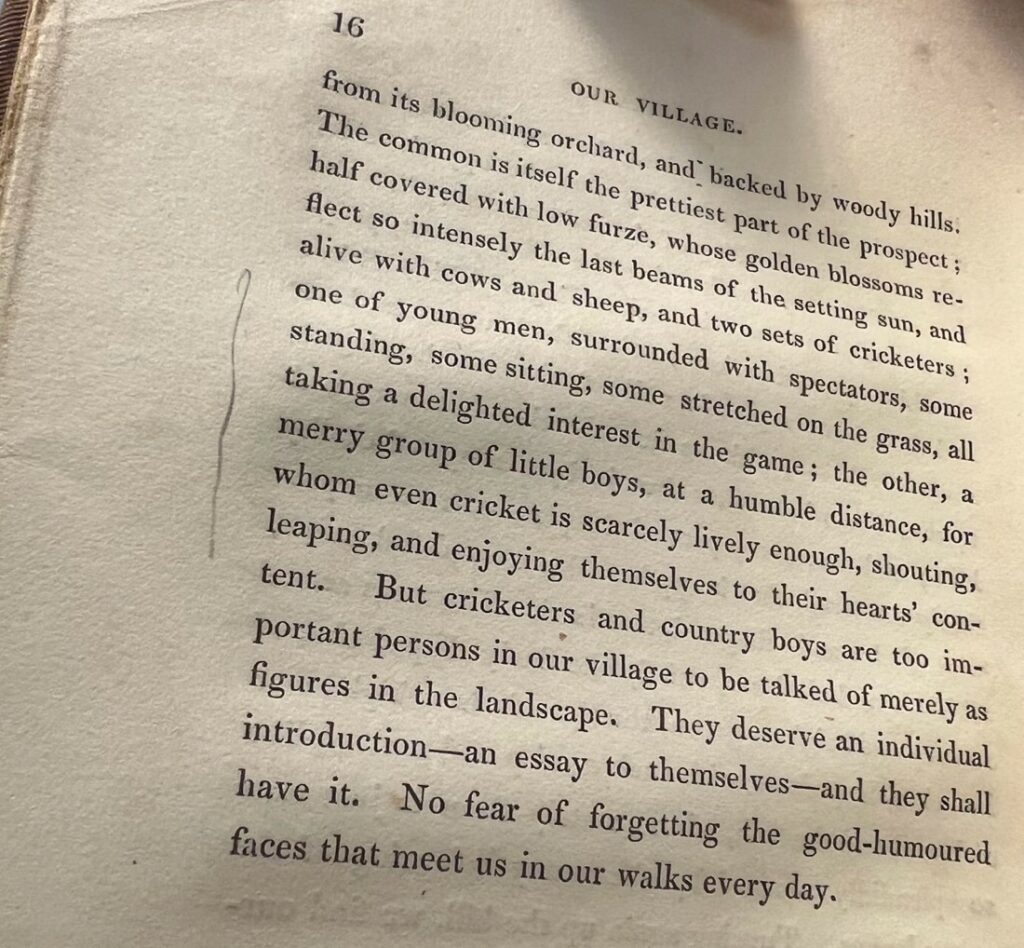

Similar to his engagement with Seward’s poetry, Blunden shared an interest in nature writing with Mary Russell Mitford. In her poetry and volume of Our Village (1832), her literary sketches paint rich details about life in the British countryside, a setting that Blunden himself appreciated deeply in his nature writing. Blunden marked several passages with pencil, including one indicating his interest in cricket, the topic of another collecting area for Blunden:

Mary Augusta Ward & World War I

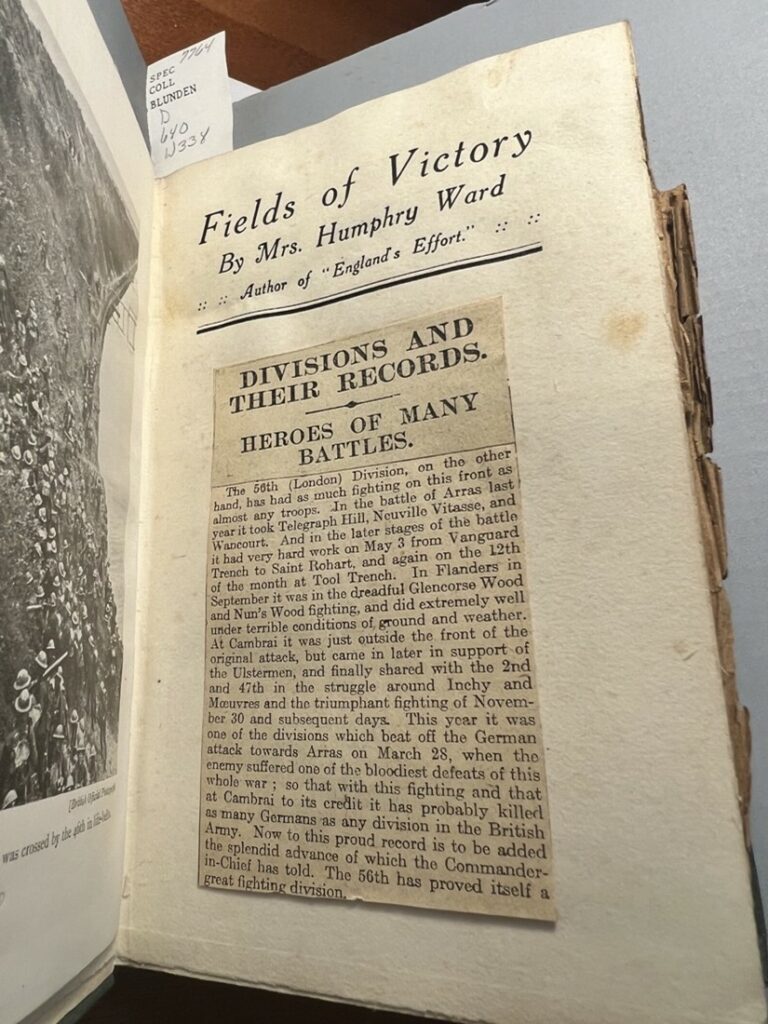

Blunden has a large collection of books written by Mary Augusta Ward, who wrote under her husband’s name, Mrs. Humphry Ward. Ward was born in 1851 and raised by her father Matthew Arnold, a noteworthy poet himself. Blunden collected some of her best-selling novels, including Lady Rose’s Daughter (1903) and The Marriage of William Ashe (1905) popular with both British and American readers. Ward lost popularity with young readers for her anti-suffrage positionality, but she regained popularity with her writing influenced by World War I, especially in one of her final writing projects, Fields of Victory (1919). During World War I, Ward met with former President Theodore Roosevelt who had asked her to write about what was happening in Britain during the war for an American audience. To enrich her writing, she visited factories, the British fleet, and the same trenches that Blunden experienced as a soldier for the British Army. Ward’s primary research earned her the title of becoming one of the first female British war correspondents, and led to several publications, including a number of articles and three books. Fields of Victory concludes a trilogy that focuses on the role the British Armies played in France during the last year of the war.

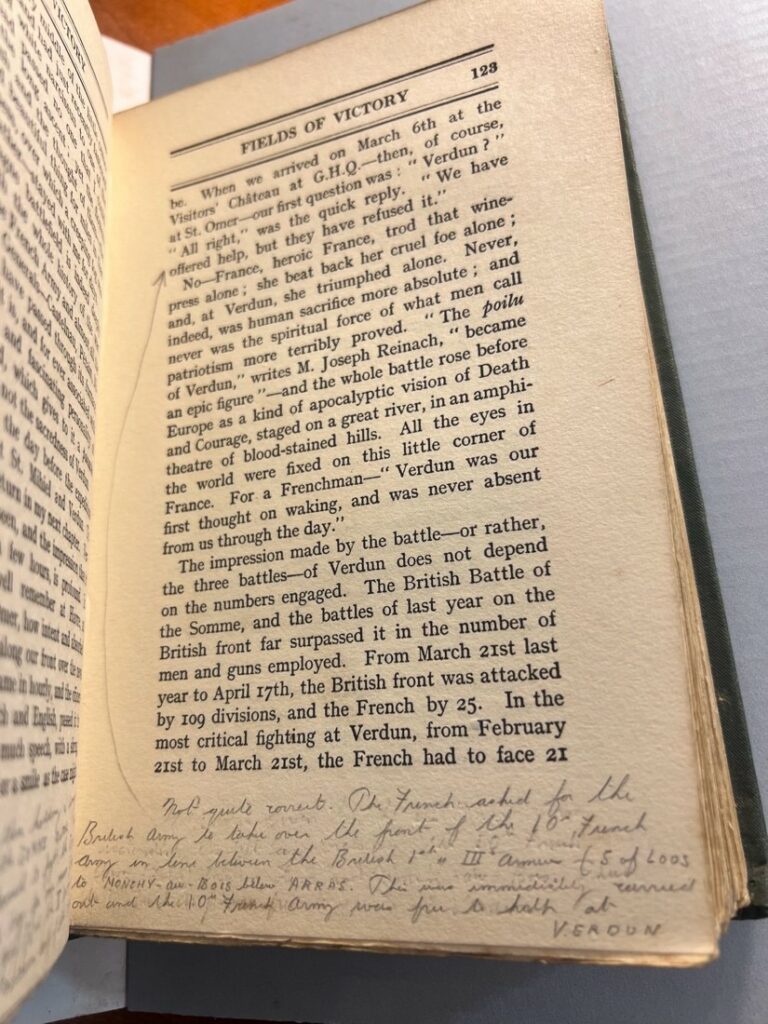

Fields of Victory has many interactive elements thanks to Ward and Blunden’s contributions. Ward included a fold-out map of the various battlefields, propaganda honoring fallen veterans, and a chart detailing the scale of casualties, prisoners, and artillery from 1916 to 1918. Knowing Blunden’s authority as a veteran himself, we pay particular attention to the clues he left behind to illustrate how he engaged with Ward’s writing. He inserted all kinds of marginalia and attached several newspaper clippings to select pages. Below are their headlines, only one retains its date:

- “Divisions and Their Records: Heroes of Many Battles”

- “From Paris to Devastation”

- “British Army’s Duty ‘Nobly Done.’ Sir D. Haig on the Allied Advance” September 4, 1918

- “British Feat of Arms. Hindenburg Line Smashed. Heroism of British Armies.”

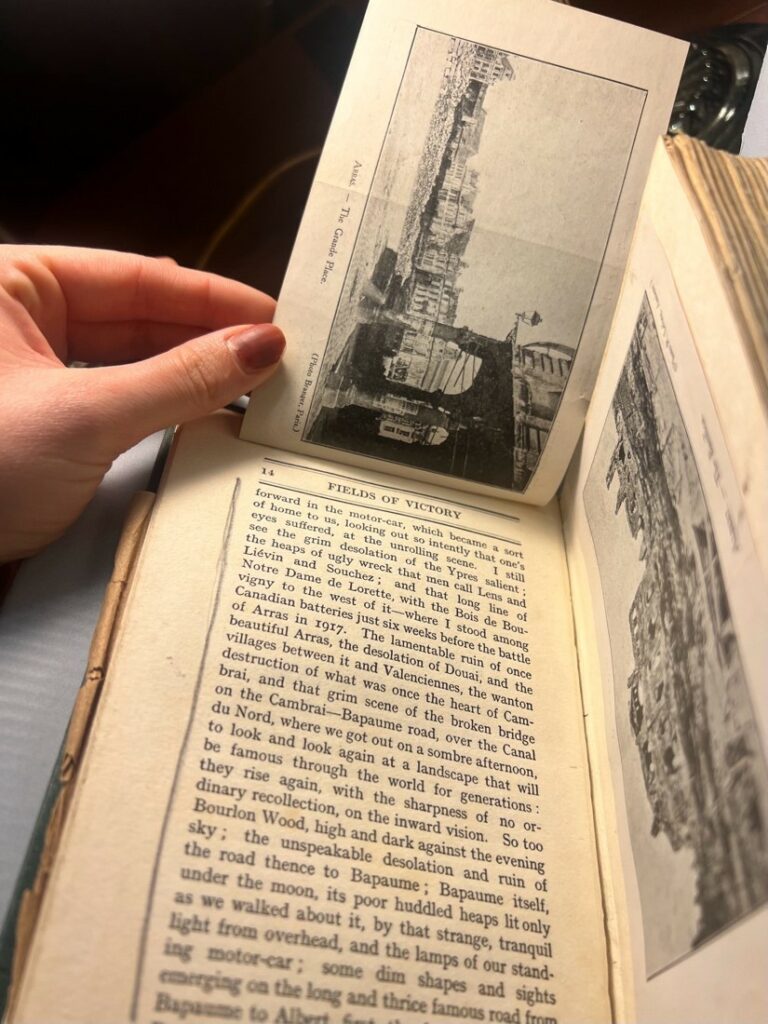

There are also several printed photos taped to pages where specific battles and locations are mentioned. These photographic additions provide a visual complement to the text. The images include:

- Arras – The Grand Palace and the Petite Place, showing the Belfry, and a Cemetery

- Albert – The Basilica

- Lens – The Mairie quarter and ruins of the church

Most noteworthy in Fields of Victory are Blunden’s written contributions to the text. Many passages are emphasized with pencil annotations, some with comments affirming or fact-checking Ward’s writing. Blunden writes “Very true” in response to Ward’s observation: “No one who has not seen with his or her own eyes the situation in Northern France, can, it seems to me, realize its effects on the national feeling of the country.” In another passage where Ward describes a negotiation of help being offered to the French from the British, Blunden adds his own thoughts beginning with the words, “not quite correct…”:

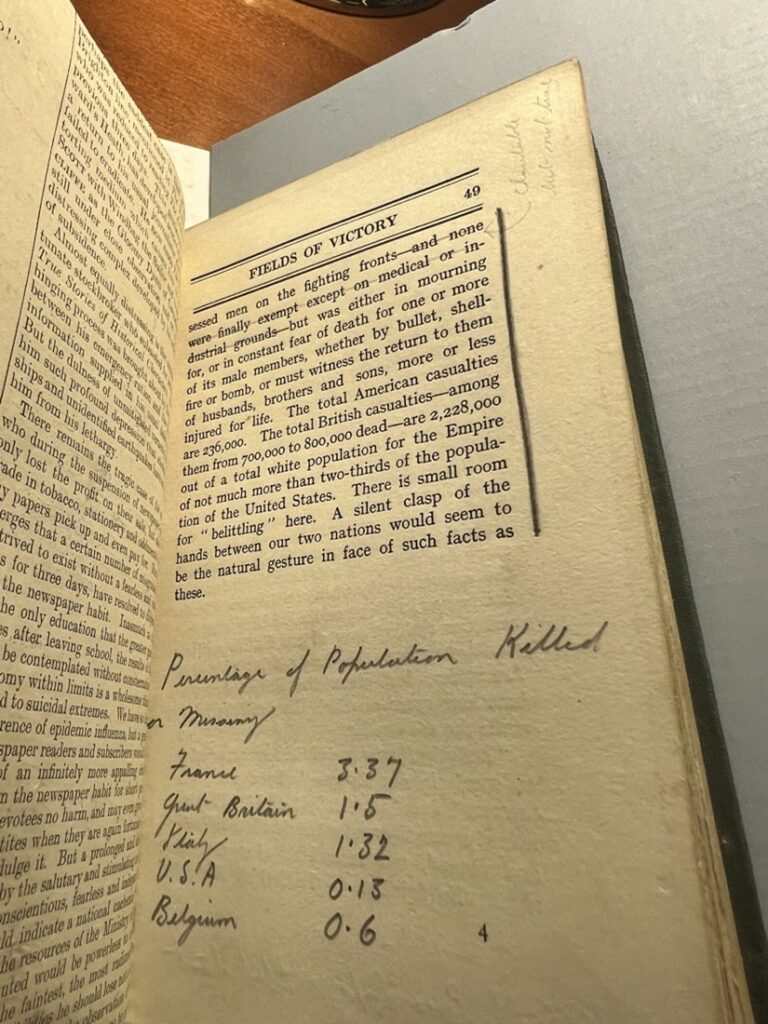

Ward also describes American and British causalities in numbers. Here, Blunden adds his own written chart about the percentage of national populations killed or missing from several countries, including France, Great Britain, Italy, U.S.A., and Belgium.

Blunden’s annotations and insertions make this book an invaluable contribution to his collection. It reads like a scrapbook that illustrates how he engaged with a text, written based on first-hand experience by a woman, in ways that reflect on very intimate details of his own experiences as a WWI solider and veteran.

Taken together, readers can learn a lot about Blunden’s collecting interests from the few but noteworthy women authors he collected. The women featured in this post were chosen for their great literary contributions and for the significant number of books that Blunden collected from each. I encourage you to read some of Blunden’s own literary contributions, like his nature poetry or his World War I nonfiction to discover inspiration in his writings from the woman authors he collected.

Alexis Voisard is the 2022-2023 Rare Books Graduate Assistant at the Mahn Center for Archives and Special Collections. She is currently researching Appalachian women’s digital writing to pursue an M.A. in English with a concentration in Rhetoric and Composition and a Graduate Certificate in Women’s Gender, and Sexuality Studies.