By Hunter Humphreys, English Pre-Law, 2023, Written as part of English 4940: Research Apprenticeship, Spring 2023

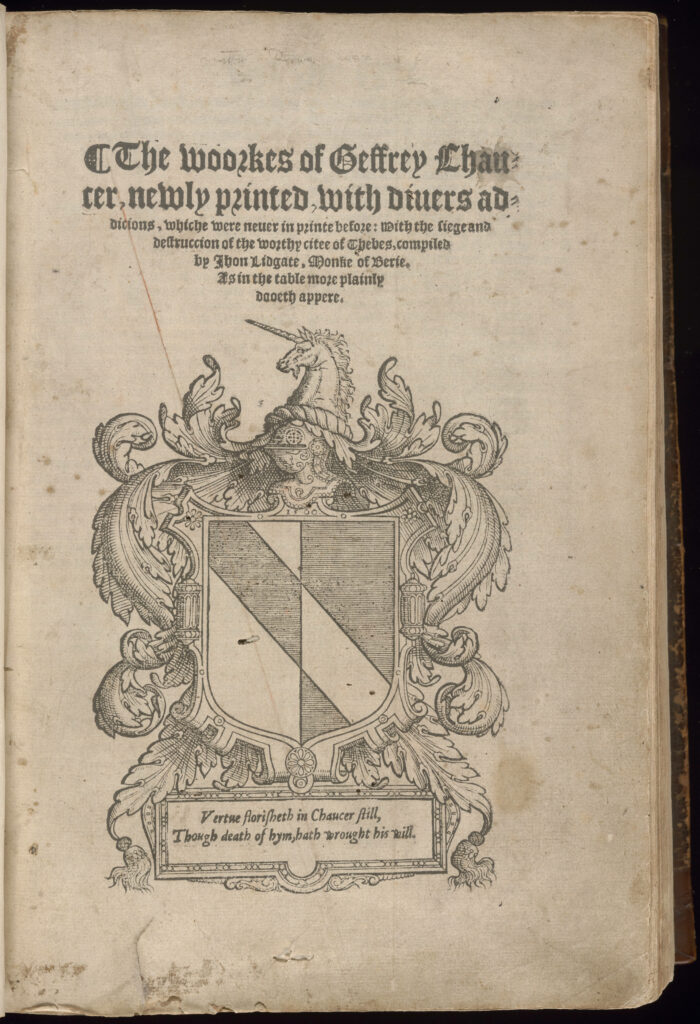

Having the opportunity to study in the Libraries’ Mahn Center has been a dream come true, and certainly a memorable experience during my career as an undergraduate student. For about a semester and a half, I was given the opportunity to research and study the rare book collection’s copy of the 1561 edition of the Woorkes of Geffrey Chaucer. Despite the author’s significance and the age of the book, not many people have sought to dig deeper into the book’s history, or the notes contained within. All of these factors piqued my interest and helped me look past the unassuming leather cover and damaged pages. While the goal of my studies has always been to uncover the secrets contained within the covers of this book, I also hope that others can find my work useful in their own research or as a valuable resource for their own exploration into this book.

How My Project Started

My research into this book began as a project for Professor Joe McLaughlin’s English 3490 History of Books and Printing during the fall 2022 semester. During the first half of the class, students learned about bookmaking and printing processes, and interacted with manuscripts, books, and other printed materials from the rare book collection. This was when I was first introduced to the 1561 Woorkes of Geffrey Chaucer. I noticed how well it had been preserved for its age and the handwritten notes found throughout the margins of the book. Later that same semester, the class was assigned a project that allowed me to revisit the book and begin researching and writing a report about it. The questions that I sought to answer were the following:

- What was the purpose of all the handwritten additions and notes?

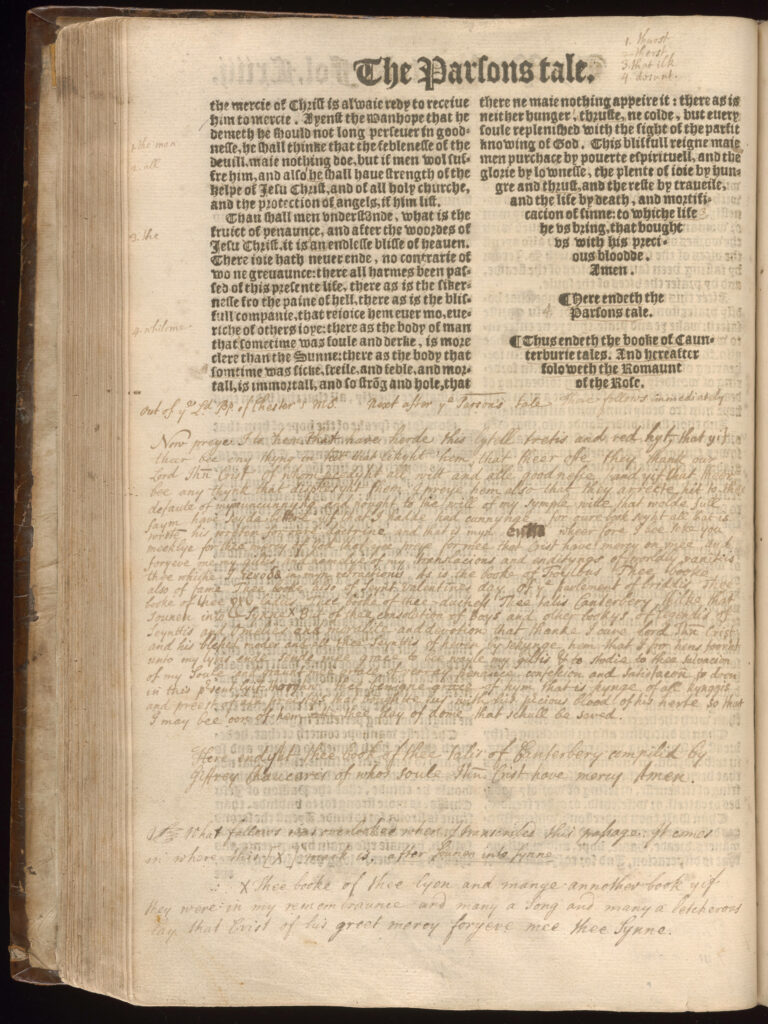

- Why is there so much handwriting at the end of The Canterbury Tales in particular?

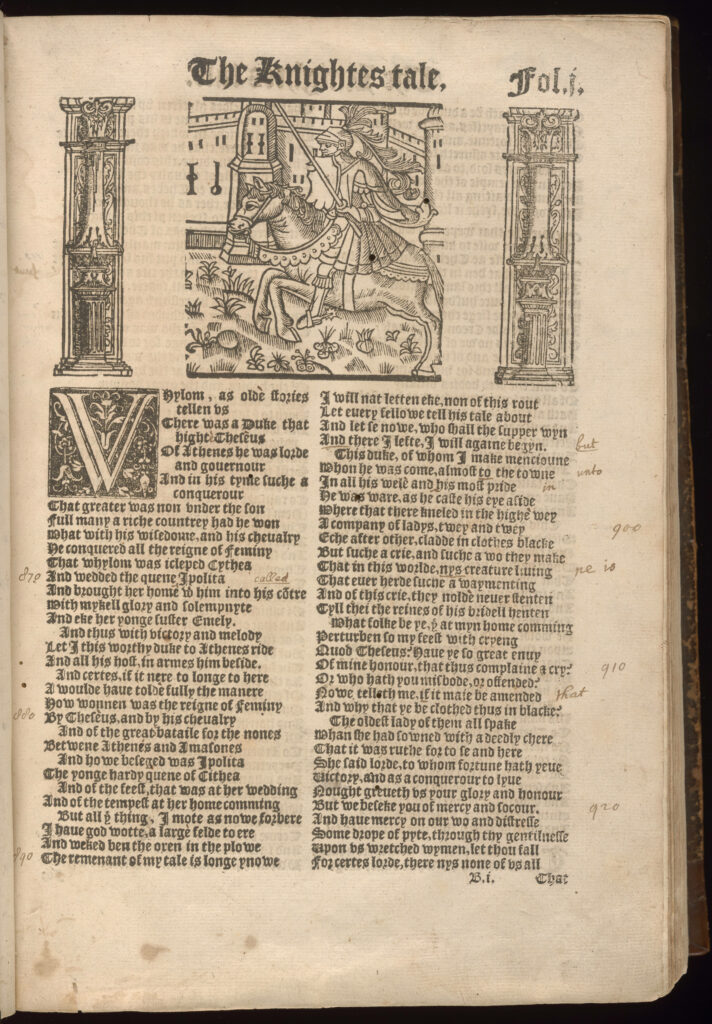

- Why was there only one woodcut for The Knight’s Tale?

- Who was William Leigh and did he write the older set of notes?

Many of these questions and a few more remained unanswered during my initial semester working with the book. However, I was fortunately given the opportunity to conduct further research and create a digital exhibit as part of an English 4940: Research Apprenticeship, an independent study course I took during spring 2023.

One major question that I was able to answer before the end of the fall semester emergred from the full title of the book: The Woorkes of Geffrey Chaucer, newly printed, with divers addicions, whiche were never in printe before: with the siege and destruccion of the worthy citee of Thebes, compiled by Jhon Lidgate, monke of Berie.

Translating from the Old English, I wanted to know, who was Jhon Lidgate [John Lydgate], the Monk[e] of Berie, and what was his relationship to this book? I learned that Lydgate was educated and worked through the Church, and wrote various poems and other works during his lifetime. He was heavily inspired by Chaucer and even knew the famous poet’s son and granddaughter, whom he was commissioned to write for. While he reached some degree of fame during his life, unlike his hero, Lydgate would never receive the same posthumous fame that Chaucer would.

Another question I was able to answer early in my research was why a previous owner included a long, handwritten addition at the end of The Canterbury Tales. This addition is known as The Retraction, and was common amongst writers around Chaucer’s time. The Retraction was included at the end of a work to serve as an apology to the reader and to God for the crude, offensive, or sometimes blasphemous content within a work. I do not know why such a custom was omitted in the 1561 edition.

I was also able to identify the purpose of the older handwritten notes. A separate individual who owned the book wrote later that the handwritten notes made by an earlier hand were for the creation of a newer edition of The Canterbury Tales, and also lists the various manuscripts and their owners and/or authors that were mentioned in later notes. One such individual was John Urry, who will be further discussed shortly.

Researching & Creating an Exhibit

At the start of the spring 2023 semester, I was greeted by interesting news. The Libraries’ Digital Initiatives Unit was working to completely digitize the 1561 Woorkes of Geffrey Chaucer. This meant that I would be unable to study the physical book for a few weeks. However, I was able to arrange a meeting with Erin Wilson, Digital Imaging Specialist & Lab Manager, who allowed me to visit the lab. She provided a demonstration of how they capture images and ensure that the images were clear before compiling and uploading them. Seeing their work, I was glad that the library could add this work to their Digital Archives so that students or other academics could view it and use the images for any research, or just to be appreciated by members of the general public who would come across it. My research yielded one other 1561 Chaucer, but it was not exactly the same as the one we have (the primary difference is in the number of woodcut illustrations included).

During this time without the book, I focused on research for my digital exhibit: A Brief Look at the 1561 Woorkes of Geffrey Chaucer. I looked for information regarding the Stationers’ Company, an English guild that had been in operation since about the 14th century and was given the position by the Crown to be the leading authority on printing and publishing in London. Most of my information came from two books, The Stationers’ Company, A History, 1403-1959 by Cyprian Blagden and Some Aspects and Problems of London Publishing Between 1550 and 1650 by W.W. Greg. Both helped me understand the roles of two individuals whose names were printed in the 1561 Chaucer: John Kingston and John Wight. The former was the printer of the 1561 edition, while John Wight was the individual who was allowed to sell the book.

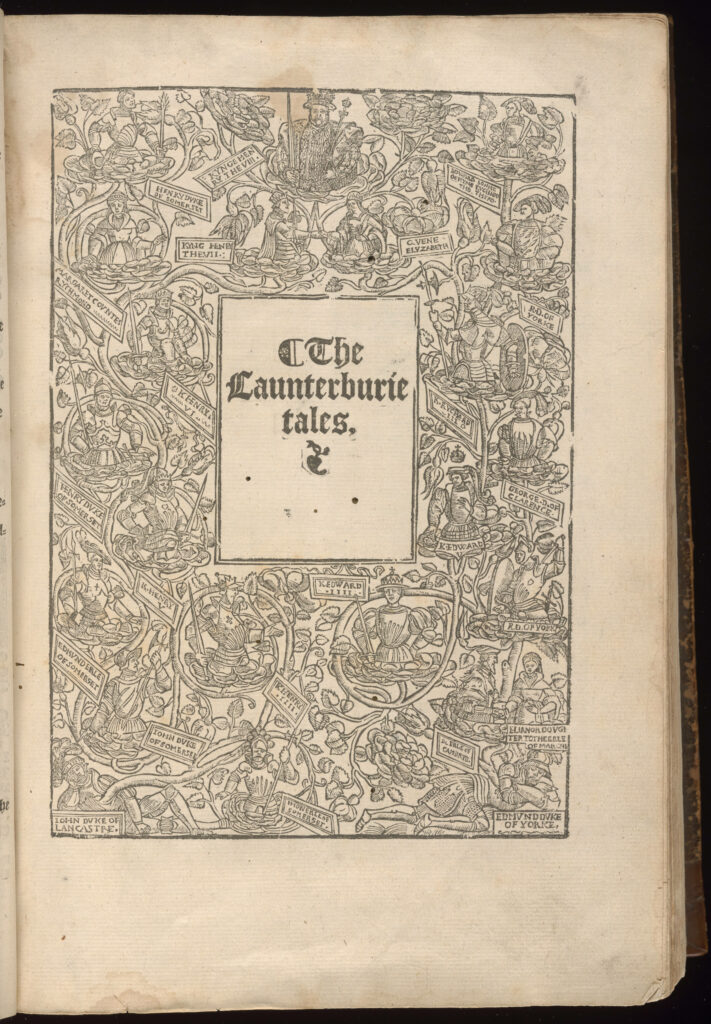

Finally, after a few weeks, I was able to see the book from anywhere online, and I was impressed by the clear, high-quality images that Digital Initiatives captured. Soon after, I discovered that John Stow was the individual who compiled the 1561 edition. This revelation was a turning point in my research, and I was now able to find more information regarding what made his edition different from any Chaucer edition or Lydgate collection before. Most of my research was done online, with a few exceptions. Prior to spring break, Dr. Mary Kate Hurley from the English department suggested that I read Megan Cook’s The Poet and the Antiquaries, Chaucerian Scholarship and the Rise of Literary History, 1532-1635, and it proved to be an invaluable resource. From this book, I discovered the origin behind the woodcut of the Lancaster and York royal family trees that join to form the Tudor line and that preface The Canterbury Tales.

Another piece of important information within Cook’s book was about John Urry. His edition of the Works of Geoffrey Chaucer was printed and published in 1721. His name being included in the handwritten notes of the 1561 Chaucer meant that the notes were written sometime possibly during the second half of the 18th century or early 19th century.

![Marginalia on the bottom of a page of "The Frankelein's [Franklin's] Tale" that includes the handwritten note: 'N.B. [Nota Bene] wherever I make such a stroke as ‒ after a word, it is a correction after Mr. Chomley M.S. the rest are Mr. Urry's'"](https://sites.ohio.edu/library-archives-blog/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/cropspeccoll_3691_full-1024x322.jpg)

Cook’s work was certainly the best resource that I used in compiling my exhibit, as it explained many of the decisions that John Stow made in his 1561 edition.

During my time researching the 1561 Woorkes of Geffrey Chaucer, I had the opportunity to meet with various faculty members from both the library and the English Department. As part of ENG 4940, I worked closely with Professor McLaughlin and Miriam Intrator, who works in Special Collections at Alden Library. They assisted me in brainstorming topics and with general knowledge about books and bookmaking during the 15th, 16th, and 17th centuries, as well as providing technical assistance for the creation of my exhibit.

Dr. Beth Quitslund of the English Department met with me twice in order to answer questions I had about the Stationers’ Company and printing and publishing practices around the 15th and 16th centuries. During our first meeting for the ENG 3490 project, Dr. Quitslund was more than happy to answer my questions and provided excellent insight into the Company’s practices around 1561. I was fortunate to have the opportunity to meet again to discuss my progress and the roles of John Stow, The Retraction, and other references included in the marginalia. While these meetings may not have produced the answers to all of my questions, Dr. Quitslund pointed me in the right direction and left me with more topics to research.

Late into the semester, I met with Dr. Hurley, who requested a meeting to see the book for herself and to offer her assistance. Her insights and knowledge of pre-1561 writings and manuscripts gave me useful clarification regarding the handwritten notes and earlier Chaucerian works. I can say for certain that my research, and final digital exhibit, would not be as complete without the assistance of these individuals and their willingness to guide me throughout my research.

Continue Your Exploration

- The digital exhibit: A Brief Look at the 1561 Woorkes of Geffrey Chaucer

- Fully digitized 1561 Woorkes of Geffrey Chaucer

- Other Chaucer related materials available in the Digital Archives

- Suggested further reading: