By GEOL 4900 students: Emily Dietz, Alexis Hunter, Lorena Jevnikar, Peter Rhynard, Kaycee Scott, and Jada Townsend

During the fall 2023 semester, students in GEOL 4900 Visual Communication in the Geological Sciences taught by professor Eva Lyon, worked with university archivist Bill Kimok and rare book librarian Miriam Intrator to include geology related materials from Mahn Center collections in an exhibit the class curated in Clippinger Hall. The exhibit is spread across display cases on the 2nd and 3rd floors of Clippinger and will be on view through summer 2024. Clippinger is open 7am-7pm, and students taking a class in the building can swipe in anytime.

In this post, students from the class who selected Mahn Center items, explain the exhibit sections they curated and their decision making processes for what to include.

Back row: Jada Townsend, Kaycee Scott, Peter Rhynard, Lorena Jevnikar. Front Row: Emily Dietz, Alexis Hunter. Photo courtesy of GEOL 4900 students.

Invertebrate Paleontology Case

Lorena Jevnikar (Senior, Geology major)

I wanted to highlight the invertebrate fossil collection housed in Clippinger Laboratories to showcase the diversity of invertebrate animals that have lived, and still live on this planet. I chose the specimens based on preservation quality and recognizability for viewers with varying levels of education on the subject. Over 50 specimens are currently on display. I arranged the specimens based on their Phylum, which is the next highest level of taxonomy after Kingdom. The phyla (plural of phylum) represented in the case include Porifera (sponges), Brachiopoda, Bryozoa, Cnidaria (e.g., corals and anemones), Mollusca (e.g., snails and squids), Echinodermata (e.g., sea stars), and Arthropoda (e.g., trilobites and horseshoe crabs). Each phylum has a wide variety of specimens on display for viewers to see the complexity of organisms belonging to the same group. We’re including a general description of each phylum and an identification sheet listing each specimen.

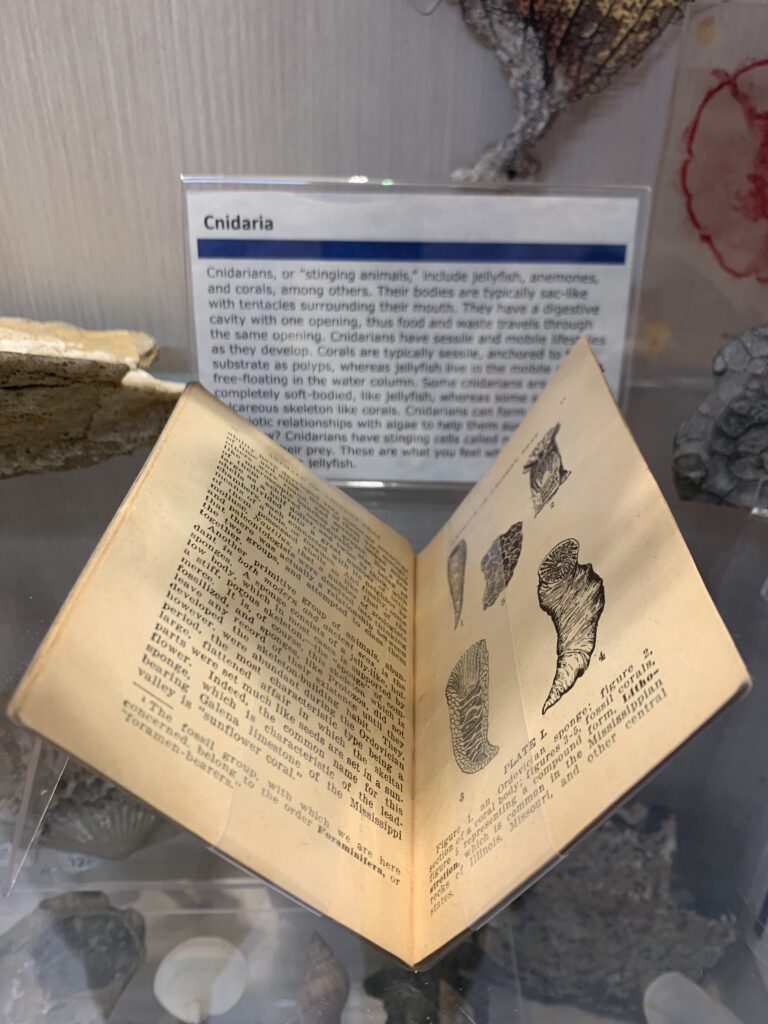

As we built this case, I wanted to incorporate different mediums to provide different learning materials for the audience. We used one book from the Mahn Center, specifically from the Rare Books Collection. I chose Animals of Ancient Seas, which was published in 1922.

Animals of Ancient Seas includes illustrations and information on the different phyla represented in the display. The book is open to a page about corals with written information as well as illustrations of corals. I loved the illustrations and thought it would be a great addition to the case. I displayed the book next to the coral specimens that the drawings are made from. It is wonderful to have this book see the light of day and be viewed by individuals who are also passionate about the subject. Thank you to Miriam Intrator for installing the book and allowing it to be part of our display.

Kaycee Scott (Junior, Production Design major, Paleontology minor)

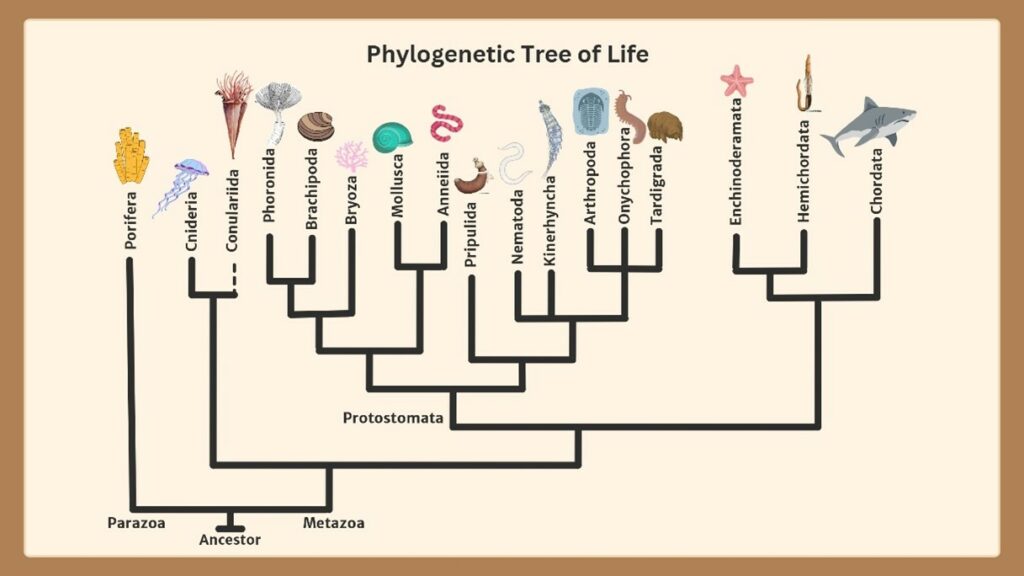

Lorena and I decided to emphasize the importance of Invertebrate Paleontology by providing a visual to convey the connections between various species. This phylogenetic tree shows the evolutionary connections between phyla. Using a number of published examples of different phylogenetic trees, particularly one that was based on invertebrate paleontology, I created the figure seen above – it is also now on display alongside examples of most of these phyla in our case. I was also inspired by a few illustrations in multiple books from the University Archives. Several books displayed their own versions of both the geologic time scales, and the phylogenetic tree of life. I was able to see how the interpretations of the geologic and palaeontologic records changed over time.

For the design, I used the sites Picsart and Canva to create the tree, as well as create the individual images of the animals. Lorena and I then picked dark grays, cream, and tan for the background and titles since it matched the colors of many fossil specimens. It also allowed for the colors of the examples to pop more for people to see. Now as the audience looks at the case, they can also see how each phylum is connected.

Ohio and Athens Geology Case

Emily Dietz (Junior, Geology and Meteorology double-major)

When starting to generate ideas for the display cases, our group wanted to dedicate two to Ohio due to the rich natural history of both the state and the Athens area. I took on the case that would feature the non-Athens area of Ohio, such as the northern part of the state, where ice sheets impacted the Ohio landscape. Ohio geology is something that I knew a little about but never took the time to dive into research until now. I wanted to express how geologically interesting Ohio is, so I started with the northern part of the state and worked my way south. Northwest Ohio and Lake Erie were shaped by continental ice sheets that advanced and retreated over millennia, creating the landscape we see today. To exemplify this Ice Age history, I chose to include a sample of mammoth hair from our collections; these massive mammals were common in Ohio until around 12,000 years ago.

Much of Ohio’s geology is not dominated by the actions of glaciers. As such, I also incorporated specimens like flint (which was used to make spear points by Indigenous peoples), a replica of the state fossil (a Trilobite known as Isotelus), and rocks utilized in the construction of canals, which varied by region based on the geology of the area where the canal was built.

I felt that all of these elements were important to include in this display case because they show not just the landscape, but also how life has used this land from ancient times to the present. These elements lead to a rich history of our state that I was very fortunate to be able to focus on and I was able to grow a better appreciation for what I see around me every day. Although I didn’t use any materials from the University Libraries’ Collections, I drew inspiration from our visit to the Mahn Center. Work continues: Future work on this display may lead to the incorporation of Ohio Geology texts from the Collections.

Peter Rhynard (Junior, Biology major, Geology Minor)

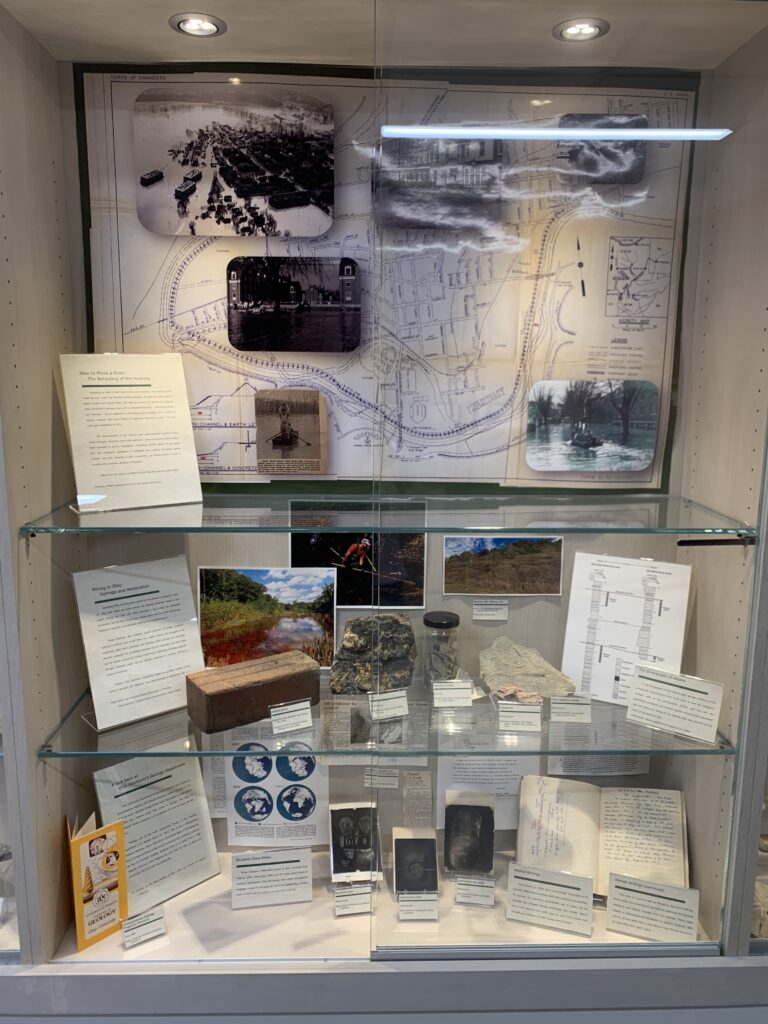

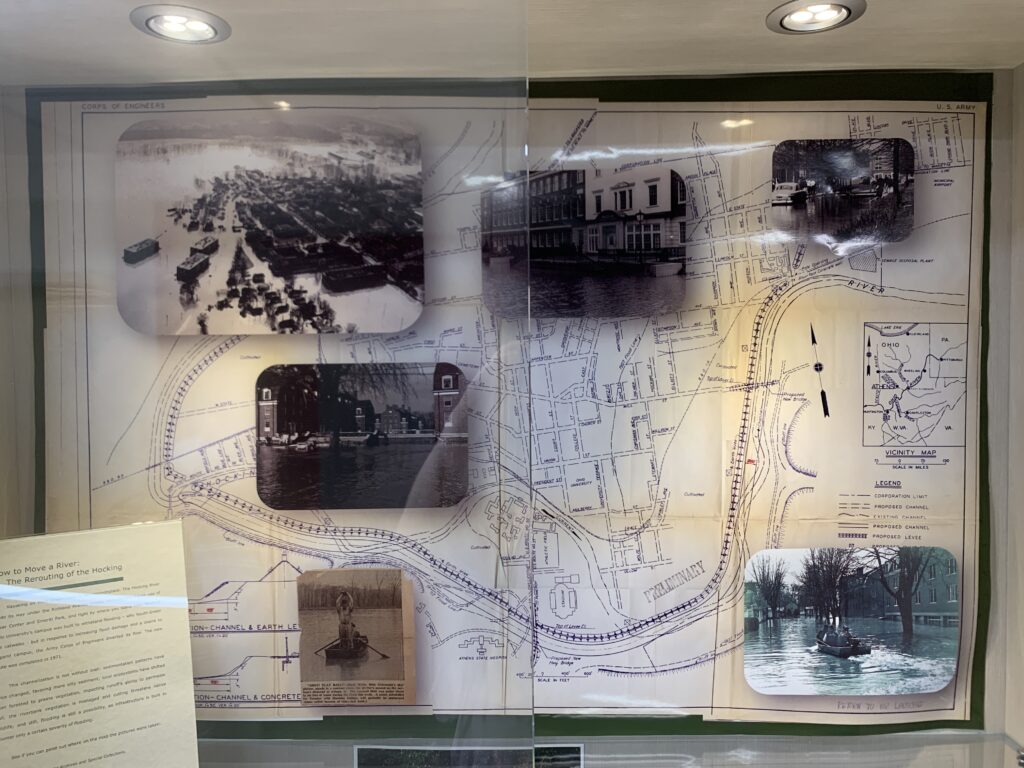

Studying geology is in many ways learning the story of how we got to the present. In this case, I wanted to tell some part of that story, to enrich the audience’s understanding of what formed southeast Ohio and give them a stronger appreciation for their place. Out of countless potential topics, I chose to focus on a few in particular: mining, because of its integral role in cultural development and its broad environmental impacts; the Hocking River channelization project, because of the proximity of the project to campus; the stratigraphy underlying the Athens area, to highlight our history in deep time; and some profiles of former faculty, to present the impact of Ohio University Geologists in the greater scientific community.

The Mahn Center provided many of the materials used in my research and presentation. One of the major components of the case is a large graphic that uses a channelization schematic and photographs of a flooded OU campus. I hope folks will walk away and consider just how much Athens has changed in the recent past (imagine kayaking through campus to get to class!).

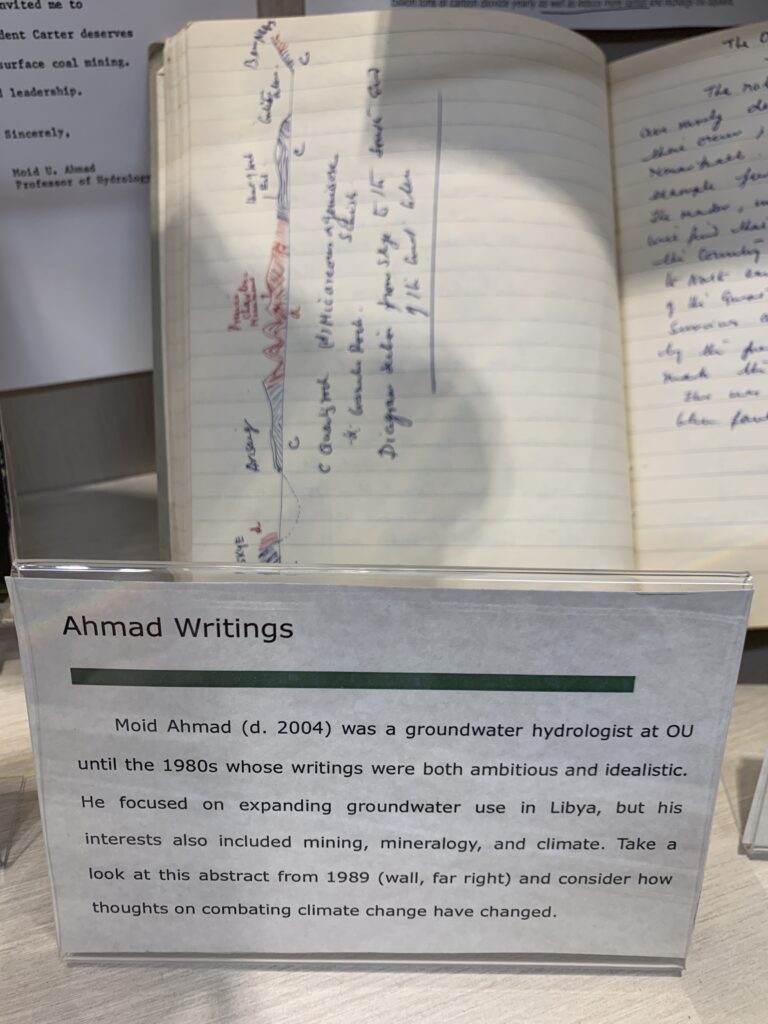

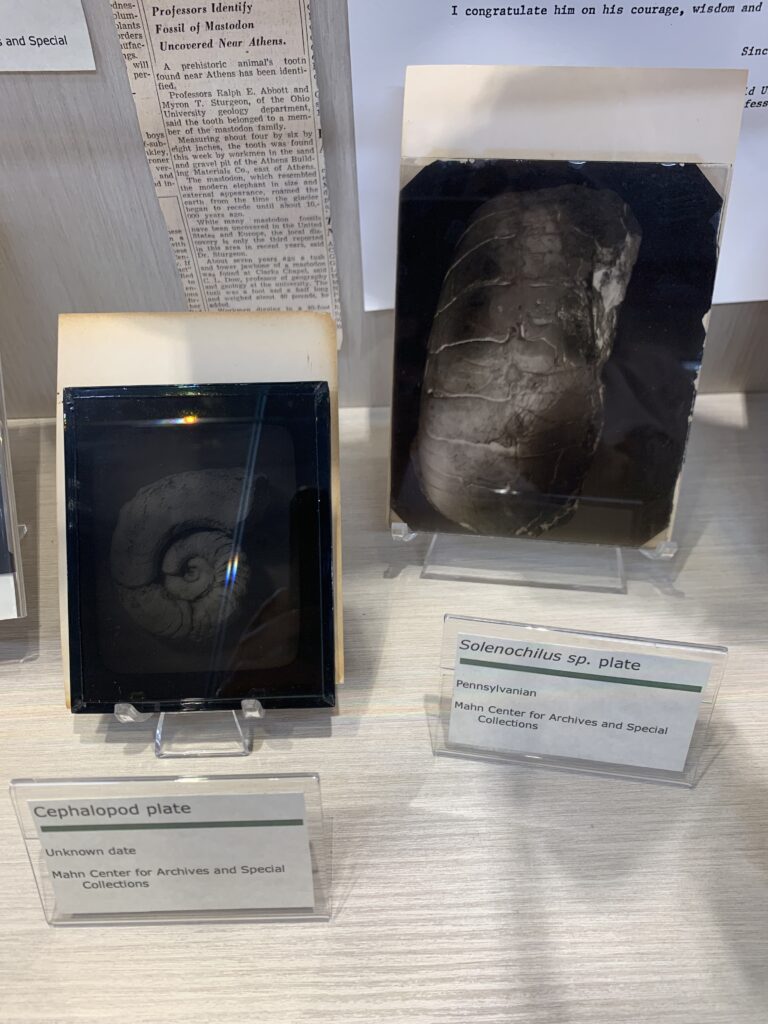

Similarly, in exhibiting work by past faculty, I wanted to give the audience a stronger sense of the work that’s been done in our department. Supercontinents, extinct animals, and climate change are all topics which have been studied here over the decades. Through the Mahn Center I was able to obtain writings, journals, glass plate photographs, and newspaper clippings which illustrate both breadth and monumentality.

Because of the number of materials, much of what I found in the archives was unable to fit in the display. As such, the next step for this case is expanding to a digital display to make more notable photographs, documents, and ephemera widely accessible.

Geology of Everyday Things Case

Jada Townsend and Alexis Hunter (Sophomores, Geology Majors)

“Geology of Everyday Things” was selected as a theme for the case outside our Intro Geology lab room. For this case, we chose to focus on a common question in intro Geology lab: Why should I care about rocks?” Our goal was to explain the different types of rocks and minerals that can be found in your day-to-day objects. Cell phones, computers, musical instruments, and oil paints are a few examples we used to draw the audience into our case.

We decided the best way to showcase our project would be to place it in the display connected to the Introductory Geology Laboratory room in Clippinger. This site is treated as a partial wall; students are able to see through the glass from the lab into the hallway, and vice versa (photo below).

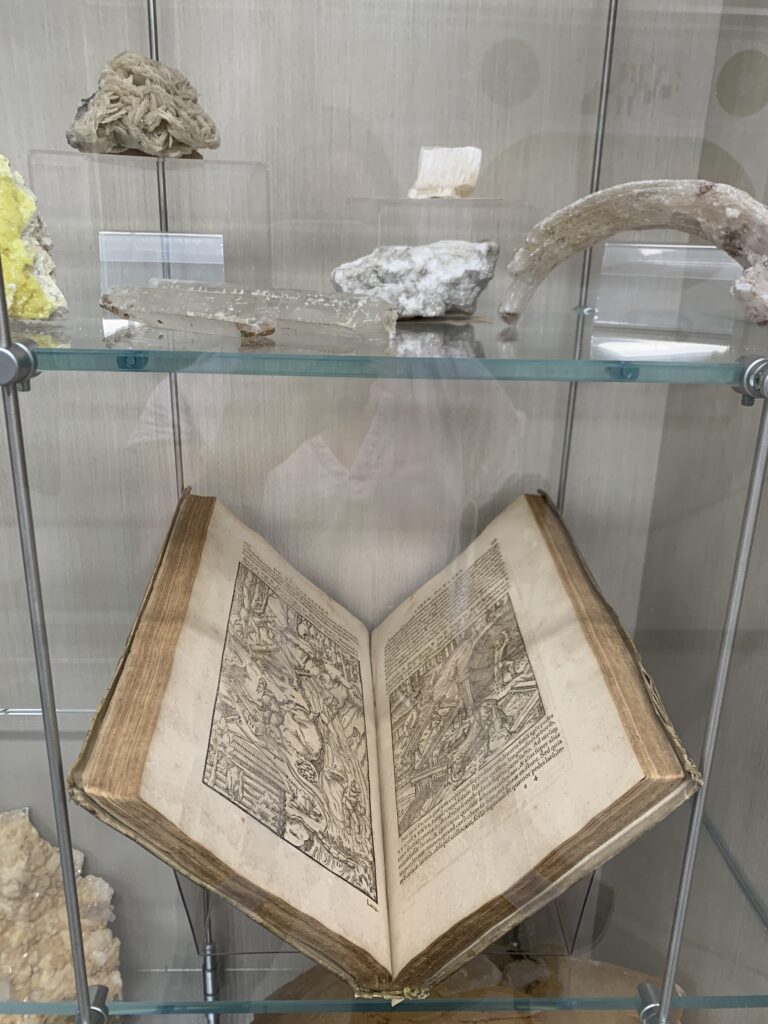

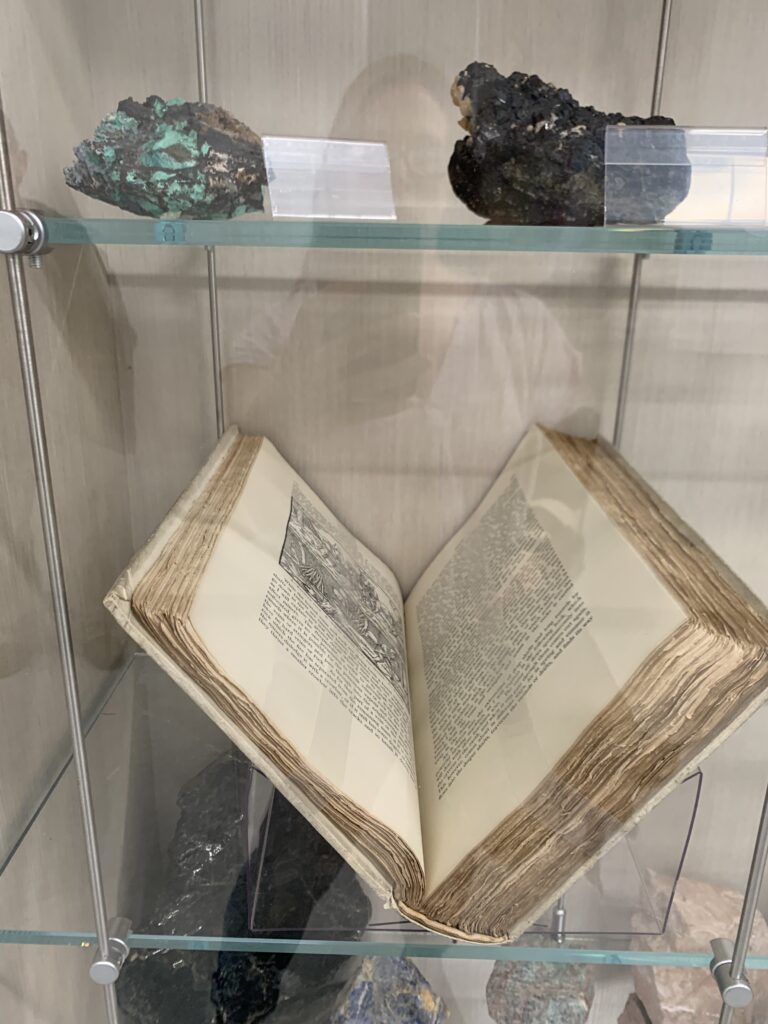

Georgius Agricola’s De Re Metallica, first published in 1556, stands as a magnum opus in the history of mining and metallurgy. Originally written in Latin, the text encapsulates the scientific knowledge and practical wisdom of the Renaissance era, providing comprehensive insight into mining, mineralogy, and metallurgy. Agricola’s work laid the foundation for systematic study in these fields. Its impact was profound, serving as the authoritative reference text for centuries and influencing the practices of metallurgists worldwide. De Re Metallica serves the role of a bridge between medieval alchemy and modern scientific approaches, contributing to the scientific revolution and shaping the future of extractive industries.

Translating Agricola’s monumental work posed a challenging task because the text contains specialized terminology and descriptions of processes that may not have had direct equivalents in English. Translating such technical content requires linguistic expertise but also a deep understanding of the subject matter. The translation into English by later United States President Herbert Hoover and geologist and later First Lady Lou Henry Hoover in 1912 marked a pivotal moment in making this knowledge accessible to a broader audience. The Hoovers’ translation not only preserved the technical precision of the original, but also reflected their commitment to historical accuracy. This translation, along with subsequent editions, became a cornerstone in the study of mining history. The 1956 edition, with its accessibility and enduring impact, further solidified De Re Metallica as a timeless resource. In the interplay of languages and editions, De Re Metallica stands as a testament to the resilience of knowledge across time, connecting the Renaissance brilliance of Agricola to scholars well into the 20th century and beyond.

De Re Metallica provided context into mining, and the process of refining minerals into materials that we can use. We thought that this relic of a book was a great example of how these ideals and practices apply even 500 years later.

The Archives and Special Collections of Ohio University went further to tell us the story of the Geology Department. With a glimpse into the university’s prestigious past, our class was given a new light and passion, adding to the history and knowledge of the Geological Sciences Department