By Jessica Licker, Master’s in Literary History, ’24, Rare Books Graduate Assistant

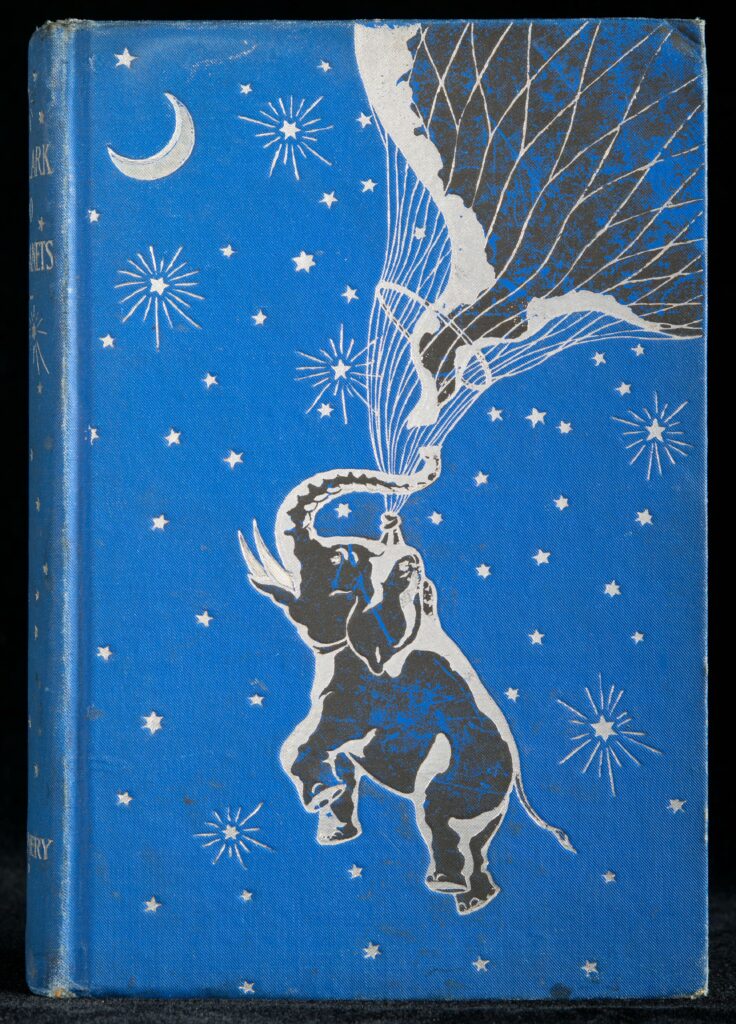

When I first started conceptualizing this exhibit, I was spoiled for choice of topics. I was quickly taken with the Juvenile Literature Collection, and the whimsy of some of the 19th and 20th century children’s book bindings, but I wasn’t sure where to take that interest. What got me started on the idea of researching the 1893 World’s Fair was pulling, for an introductory lesson on 19th century publishers’ bindings, a copy of On a Lark to the Planets by Frances Trego Montgomery. If you see the exhibit in person, you might notice that On a Lark to the Planets is not among the books showcased, and that’s because it is in no way related to the World’s Fair (regardless, I do highly recommend taking a look at it, as it is rather beautiful).

It was the cover illustration of On a Lark to the Planets that sent me down a rabbit hole of curiosity. The silver-stamped elephant and hot air balloon on the cover snagged on the edges of my childhood fascination with the World’s Fairs, and reminded me of the unfortunate fate of Topsy the elephant and the “War of the Currents” between Thomas Edison and Nikola Tesla. Edison’s General Electric lost the contract for electrifying the 1893 World’s Fair to Tesla’s Westinghouse and the Fair was a spectacular “City of Light” featuring a Great Hall of Electricity where Tesla’s alternating current power was on display.

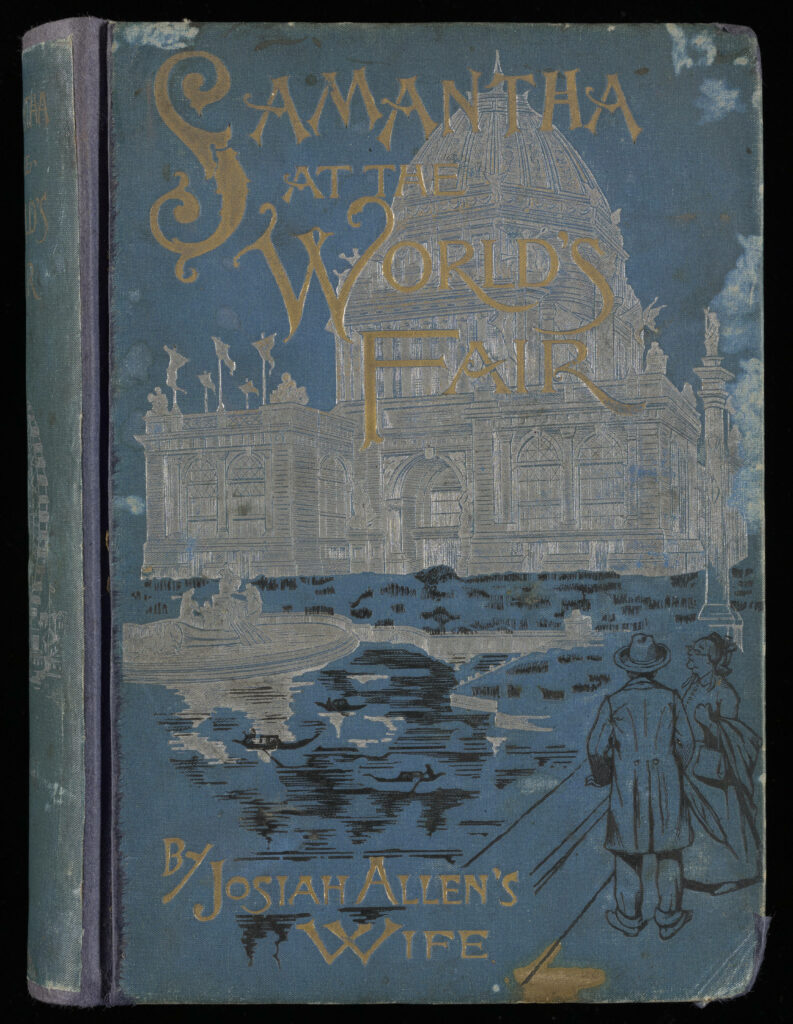

The World’s Fair theme finally, serendipitously, solidified into a starting point when I pulled the book Samantha at the World’s Fair by Josiah Allen’s Wife (a pen-name used for the Samantha series by the satirical author Marietta Holley). The palladium-stamped Ferris wheel on its cover and the story told in dialect was full of useful, funny, and informative content that was invaluable in helping me begin to understand the fervor for all things Christopher Columbus in the United States in 1893. After finding Samantha at the World’s Fair, I did a keyword search in the libraries’ ALICE catalog for different combinations of the terms “1893,” “World’s Fair,” “Columbian Exposition,” and “Chicago,” trying to cover common key words used in texts about the event and the different names the event went by. I found more materials in the rare book collection than I could ever have hoped to use for this project. Over a few days spent skimming the contents of books, I narrowed my resources down to:

- Samantha at the World’s Fair

- The World’s Fair Book for Boys and Girls: Being the Adventures of Harry and Philip with their Tutor, Mr. Douglas, at the World’s Columbian Exposition

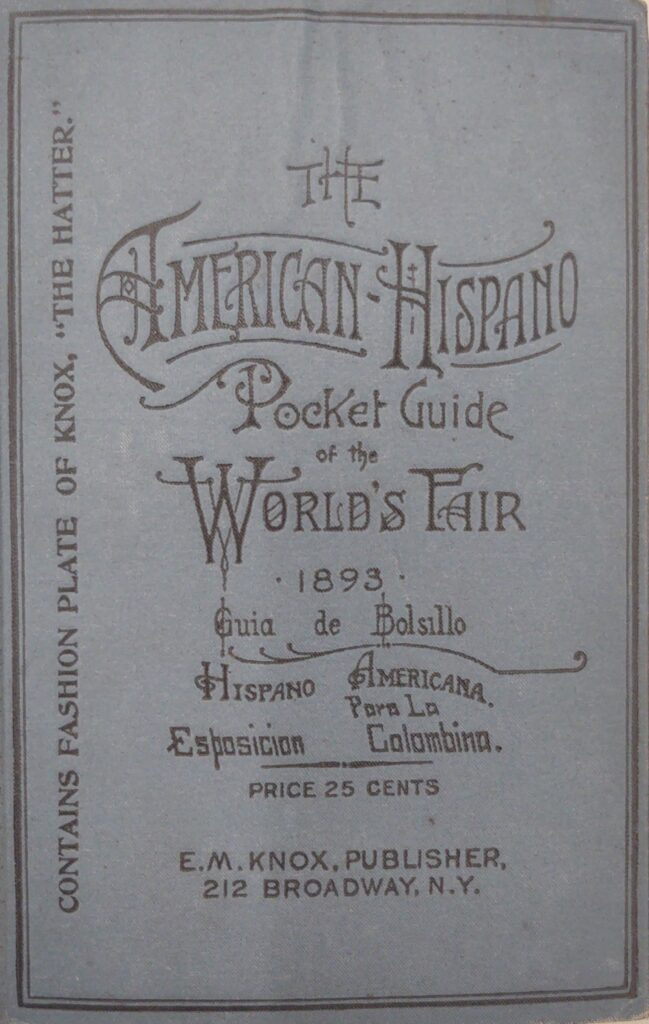

- The American-Hispano Pocket Guide of the World’s Fair 1893

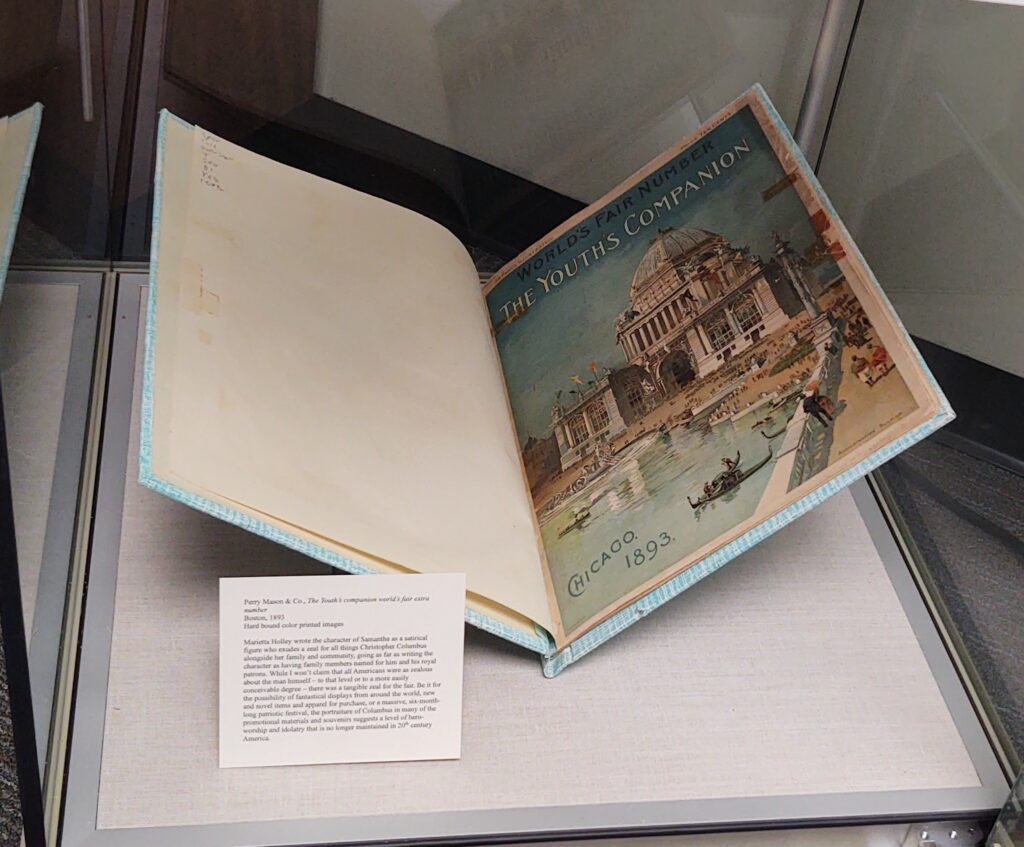

- The Youth’s Companion World’s Fair Extra Number

- Gems of the World’s Fair: Over Two Hundred Photographic Views

- Gems of the World’s Fair and Midway Plaisance: The World’s Fair in Picture and Story

I also sought out more recently written sources to provide a retrospective/reflective history of the 1893 World’s Fair. A few excerpts from Stanley Applebaum’s The Chicago World’s Fair of 1893: A Photographic Record are used in the explanatory text accompanying the materials on display in the exhibit. The biographies Marietta Holley by Jane Curry (1996) and Marietta Holley: Life with “Josiah Allen’s Wife” by Kate H. Winter (1984) were also valuable in helping me situate Samantha at the World’s Fair in its author’s life and situate my research within the cultural values and zeitgeist of the era. Biographical information is also featured within the explanatory text beside the exhibit materials. To allow for more flexibility with where and when I could sort through the information offered in the historic sources, I sought out digitized versions of the books I used for this project as I found them, though I wasn’t able to find digital copies of all the books.

As I was writing the short introduction to the exhibit, I recognized a gap in how I was presenting the information and in the books and excerpts I had chosen to exhibit. Underlying my research and writing processes was the understanding of the inequities of the World’s Fair, in which the BIPOC international and Indigenous American representatives at the Fair were not provided adequate accommodations and were treated as spectacle rather than as people. This dehumanizing reality ended, very tragically, in fatality for many as Chicago’s extreme weather conditions set in between the beginning of the Fair on May 1st and its end on October 31st of 1893. However, in my first iteration of selecting what pages displayed books would be opened to, or what covers would be displayed, I realized how few of the items directly discussed or depicted the atrocities beyond subtext, and how little space was afforded to those so devastatingly harmed. Going back through the other items in the rare book collection, I added Gems of the World’s Fair and Midway Plaisance: The World’s Fair in Picture and Story for the photograph of two people that the book describes as the “Representatives of the Dahomian Cannibals.”

In this photographic record, only passing mention is given to the discomfort felt by and inadequate accommodations given to the international representatives who were displayed as novelty in the ethnological expositions, better known today as human zoos.

The caption associated with the image on the left is the extent of that acknowledgment. It states that the individuals pictured have “begun to adapt themselves to their American surroundings” through the clothes and other fabric materials they donned for warmth. The editors note that, once cold weather arrived in October, however, they “lost interest in everything except desire to return to their native country.”

Though there are surely more examples directly discussing the inadequate accommodations provided for the representatives of countries from more temperate climates for the sake of a stereotyped aesthetic authenticity, this was the most egregious example I found to be documented and readily available within the rare book collection.

One source I wasn’t able to dedicate as much space in the exhibit as I wanted to was The American-Hispano Pocket Guide of the World’s Fair 1893. It’s a wealth of knowledge as a travel guide, mainly focused on West-bound travelers coming into America from a transatlantic voyage, and it gives fantastic insight into the minute details of travel, finances, and social expectations for the era. In bisected, bilingual pages (English and Spanish), it lists minutia down to the smallest detail like what to expect from taxi fares, depending on the number of people and suitcases you have, and branches off into sharing hotel and restaurant recommendations near the docks, and providing resources along the route West-bound visitors would likely take to Chicago. The book was published by E.M. Knox, better known as “Knox the Hatter,” and includes a glimpse into the fashions being worn in 1893 through a collection of illustrated fashion plates detailing the different styles of hats available for purchase.

1893 was not the first time a Western colonial power hosted an attempt at a global exposition. The 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago did differ from the 1851 World’s Fair in London’s Hyde Park, which is often credited as the first World’s Fair, in that its function was not to showcase exclusively the spoils of Great Britain as a colonial power, but to showcase the global progress that had been made since Columbus’s 1492 voyage. This is not to say that the 1893 World’s Fair didn’t celebrate colonialism. It’s official name as the World’s Columbian Exposition and the timing of the event to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Columbus’s 1492 journey to the Americas in search of a Midwest passage intentionally celebrated the outcomes of the colonization of the Americas and the subsequent role of America as an imperial power. The focus on globalization and the underlying current of globalization as an achievement by and for the benefit of Western countries is what underwrote the 1893 World’s Fair. Beyond that, it is very American to view our World’s Fair as the first and best, against all opposing fact.

Please visit the physical exhibit during spring and summer 2024 in the Dean of the Libraries’ suite on the 5th floor of Alden Library.