By Jessica Licker, Digital Literacy Librarian, Athens County Public Libraries, Master’s in Literary History, ’24, Rare Books Graduate Assistant, 2023-2024

At the end of the fall 2023 semester I began searching the Mahn Center rare book collection for anything related to fiber crafting. I was interested in experimenting with historic knitting or sewing patterns through the rare books as part of my graduate assistantship. My research over the course of that experience last academic year has now culminated with an exhibit, which will be on view on the 3rd floor of Alden Library through the end of spring semester 2025.

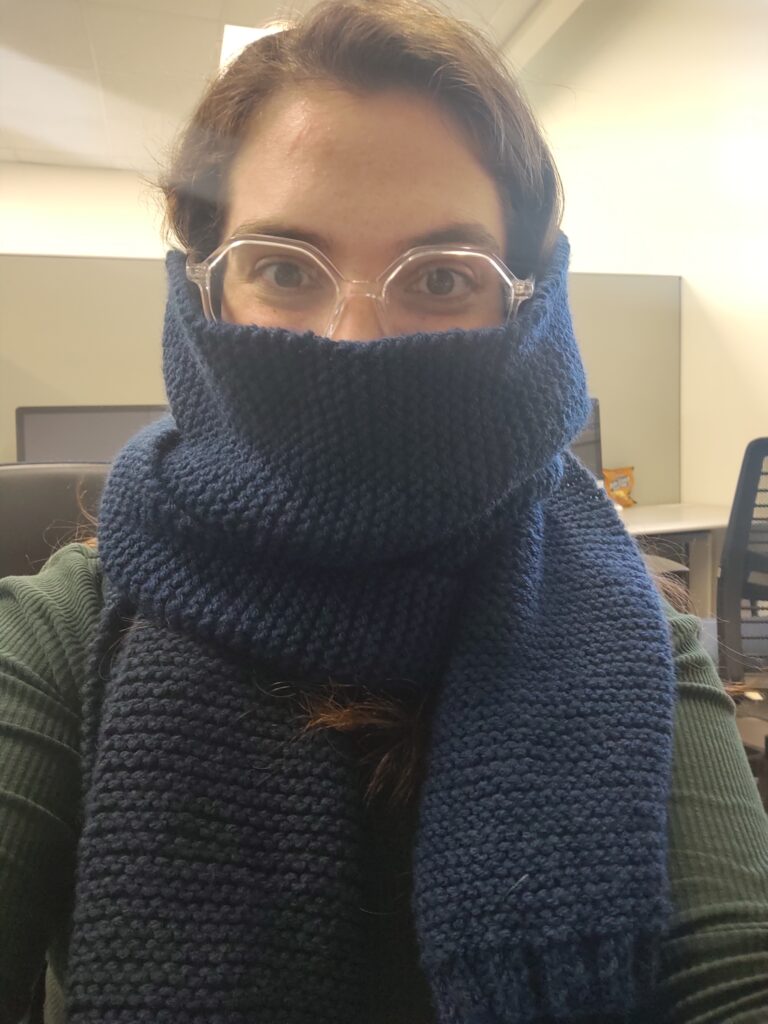

The exhibit features the results of my knitting and sewing experiments, everything from hats and scarves to a pillow cover, alongside the books that inspired me (listed below).

Narrowing down the selection to the 19th and 20th century instructional manuals and pattern books, the books I started this project with are as follows:

- The ladies’ hand book of fancy and ornamental work, comprising directions and patterns for working in applique, bead work, braiding, canvas work, knitting, netting, tatting, worsted work, quilting, patchwork, etc. compiled from the best authorities by Miss Florence Hartley (1859)

For full text: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/loc.ark:/13960/t8df7d324 (HathiTrust) - The ladies’ self instructor in millinery and mantua making, embroidery and applique, canvas-work, knitting, netting, and crochet-work (1853)

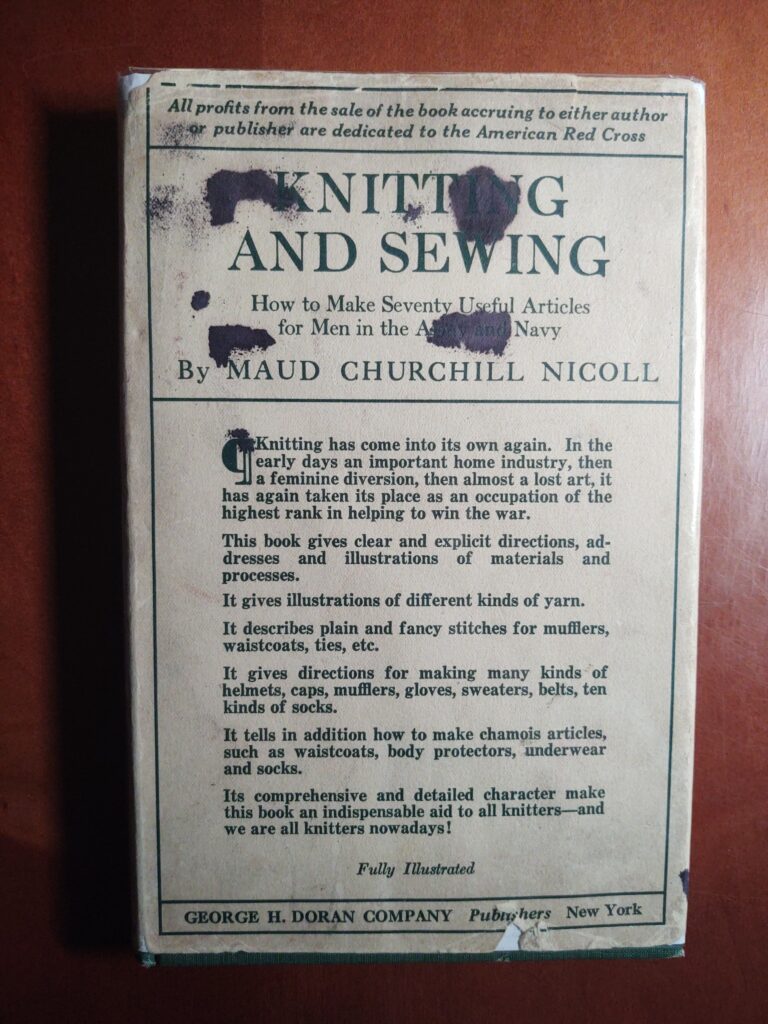

For full text: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=caia.ark:/13960/t1pg2sx3x&seq=9 (HathiTrust) - Knitting and sewing : how to make seventy useful articles for men in the army and navy by Maud Churchill Nicoll (1918)

For full text: https://www.loc.gov/item/18017769/ (Library of Congress) - The Art of Modern Lace-making (1896)

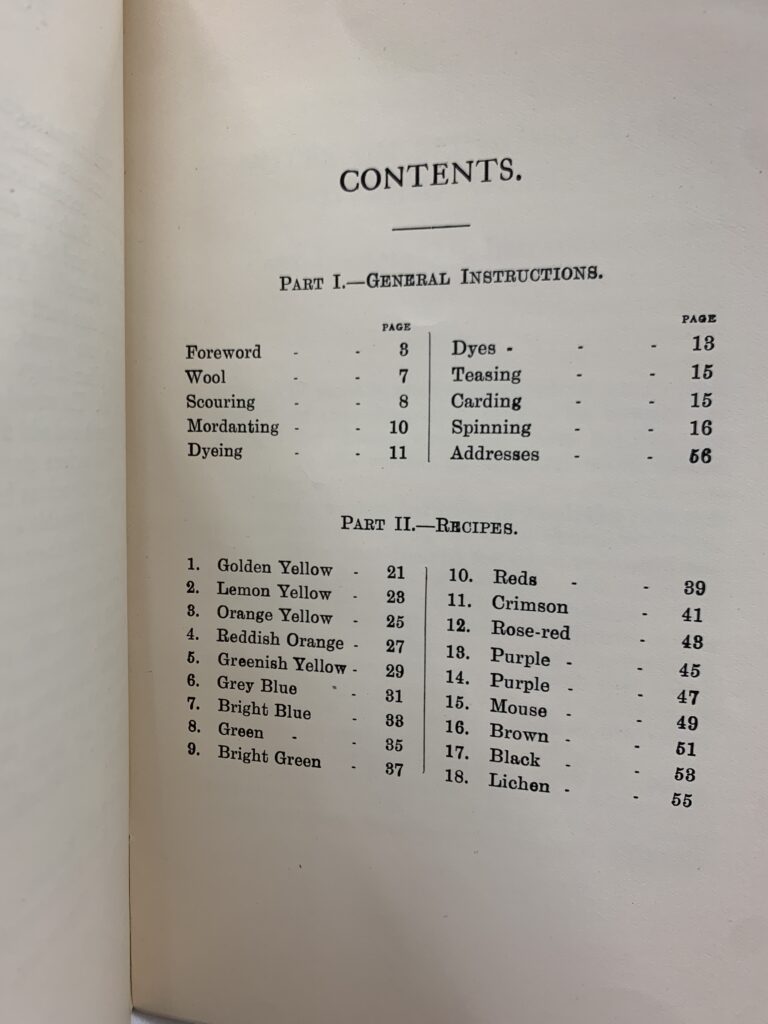

For full text: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/22325/22325-h/22325-h.htm (Project Gutenberg, 1891 edition) - Notes on Spinning and Dyeing Wool by May Holding (1922)

Full text not available online.

Knitting and Sewing: How to Make Seventy Useful Articles for Men in the Army and Navy by Maud Churchill Nicoll (1918)

There is a surprising diversity of techniques and materials present in the small selection of texts in the Mahn Center’s collection. I originally had lofty goals of learning a new skill or two and attempting to make a pattern from each book, all the while chronicling my progress. I have succeeded, at the very least, on the last account, photographing the making of each project and keeping notes about my progress, successes, failures, and mistakes along the way. I started with the knit scarf pattern from Knitting and Sewing: How to Make Seventy Useful Articles for Men in the Army and Navy by Maud Churchill Nicoll (1918), and this text ended up being my primary guide and inspiration.

Maud Nicoll

In the book’s introduction, the author’s husband (Delancy Nicoll) notes that the book is the product of his wife Maud’s time convalescing in London. After joining a YWCA nursing program in 1914 and heading to Europe for service in July of 1915, she was hit by a car, barely surviving. She became an incomplete paraplegic after the accident and dedicated herself to knitting and sewing for the troops, with friends from the front lines sharing what they needed most and found most comfortable while visiting her back in London while on leave (v-vi). This short biography, as well as mention of her in a similarly short biographical entry about her husband, is all the information I’ve been able to find about Maud Churchill Nicoll. However, her personality and convictions are evident in her dedication to the war effort and the comfort of front-line personnel, and in the meticulous detail she put into the instructional design of her patterns.

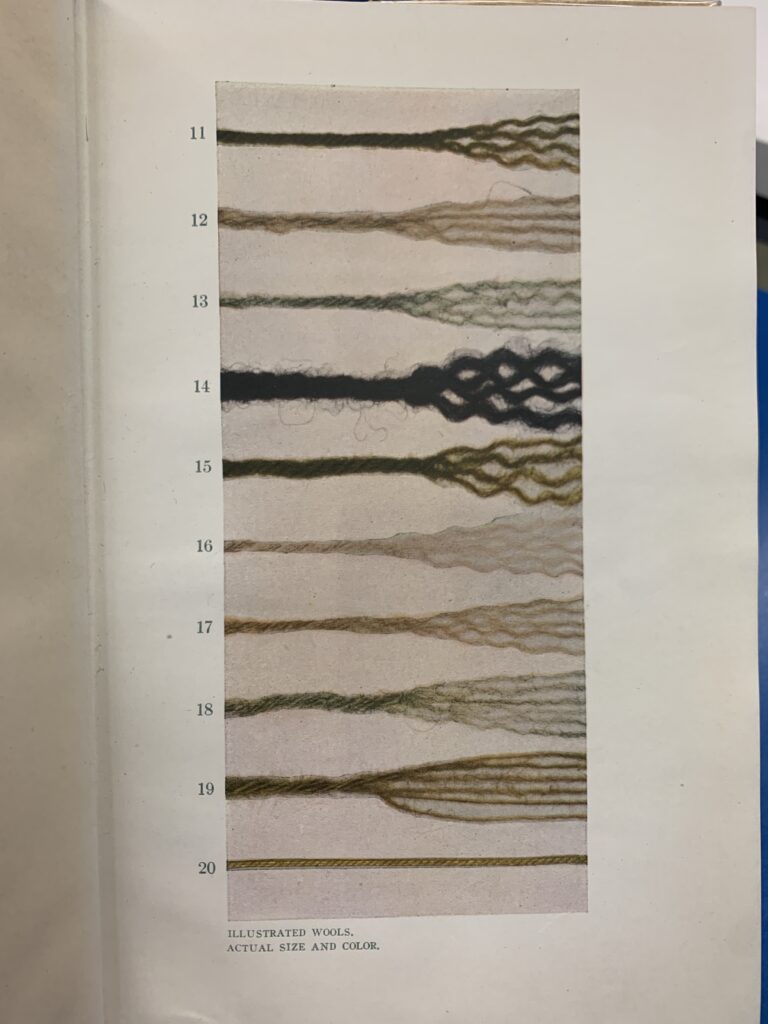

The utilitarian nature of the articles Nicoll designed, paired with their step-by-step instructions, measurement guides, stitch counts, and photographs of the finished products, made this pattern book very approachable. Despite the guidance and the warning from the author that some instructions would differ between the American and British sizing charts, material names, and technical vocabulary – and that she was writing with British terminology – it took me until my fourth pattern to question whether the UK uses a different standard for needle gauge sizing. They, alas, do, and my muffler suffered for that, coming out far larger than the pattern intended it to – though still quite cozy – as I made it with needles that were two sizes too large.

There were a few patterns I was interested in, in the other books, that I didn’t try initially because the recommended needles were noted as half sizes that just weren’t accessible to me, and for some of which I couldn’t find a modern equivalent. Since different patterns in Maud Churchill Nicoll’s book kept my interest, I stuck with her patterns as I continued the project. I conceded historically accurate fiber content for the sake of budget, making the scarf and muffler patterns with acrylic yarn in the pattern-recommended military color schemes. But, as I chose more patterns from the book, I began to give up on the vestiges of aesthetic historical accuracy that I’d been holding onto.

What I Made & How I Made It

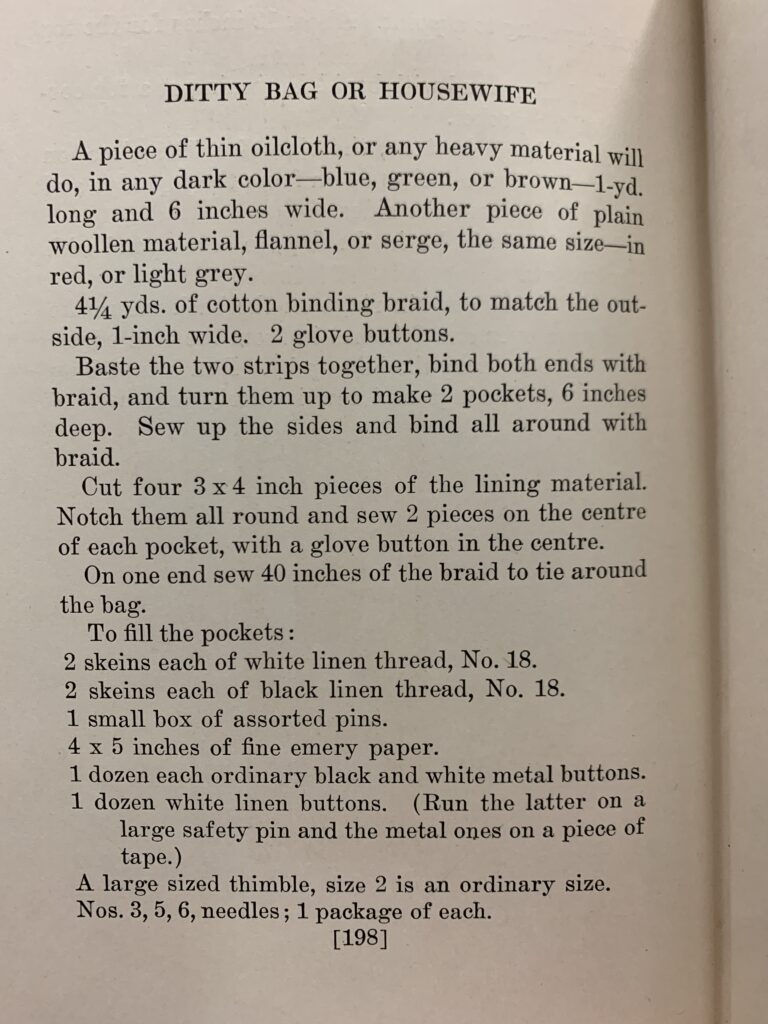

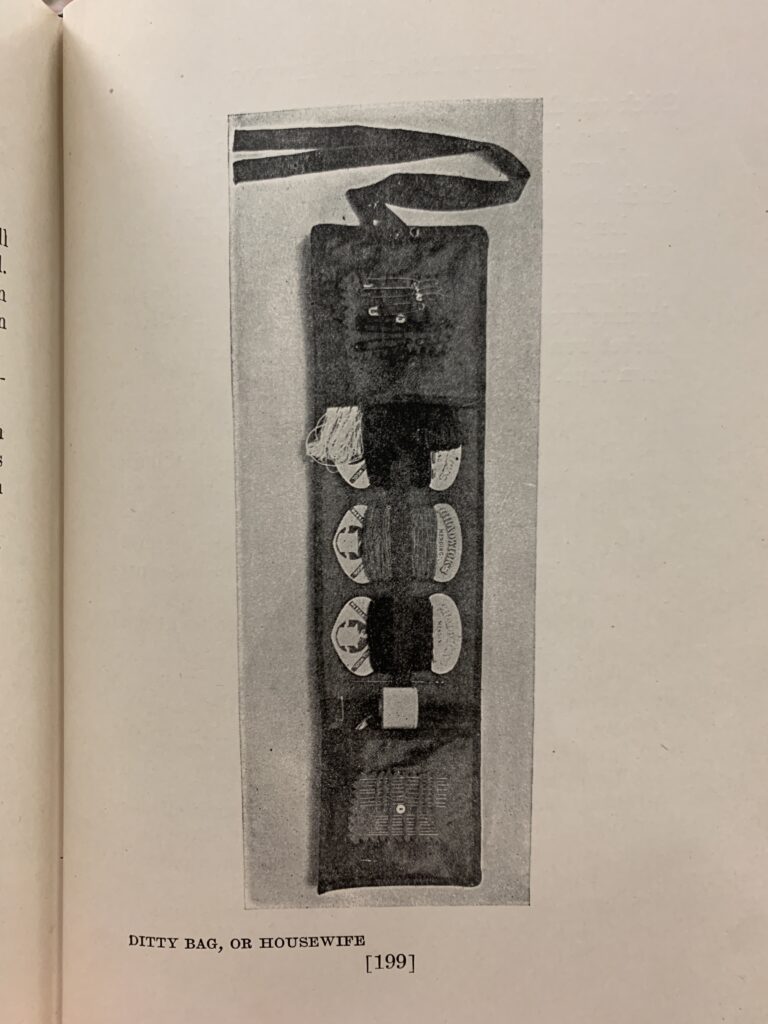

The ditty bag (old sailing term for the bags sailors used to store their tools and personal items)/Housewife (portable sewing kit) pattern called for oilcloth and flannel.

Modern oilcloth is made with PVC, as opposed to historical methods that often-included heavy metals and turpentine, mixed into linseed oil. Modern oilcloth, as available to me at Joann Fabrics, was outside my budget, not available in the colors the pattern recommended (solid blue, green, or brown), and were – for the most part – very, very floral. For full transparency, I own some fabric of equivalent weights to the recommended oil cloth and flannel. However, I was fully resistant to making a Housewife patterned with orange slices on the outside and rainbow plaid on the inside. Instead, I chose uniformly thinner fabrics, using cotton canvas toile for the outside and unbleached cotton muslin for the lining fabric, and hand stitching with mercerized cotton thread.

Leaving behind the goal of aesthetic historical accuracy allowed me to customize the patterns to my own interests and experiment with materials, while still using pattern-contemporary construction methods and creating an end product I was happy with. I still followed the limited construction instructions, but where the Housewife pattern instructed me to baste together the shell and lining fabrics, I got to be creative with it, basting along the stripes printed on the toile.

For the latter patterns, I chose yarns that were accurate to the patterns’ weight requirements, and in some cases, yarns that were closer to the pattern recommended fiber contents, but instead of army and navy regulation khaki, blue, green, brown, and grey, I knit thumbless half mittens in sage green, wristlets in a gradient reminiscent of peacock feathers, and an air pillow cover in emerald green. The goal had become prioritizing historical adequacy in construction methods – as historical accuracy isn’t really possible when working with modern materials and tools – rather than attempting to maintain a militaristic color scheme for aesthetic accuracy.

My Research Process

In my research journal, I tracked the thought process that led to my acceptance of historical adequacy as the goal and tracked my questioning of contemporary construction methods as follows:

I’ve come to terms with the colors being fun, festive, and not historically accurate. The question is, should I compromise further in the materials and construction methods? The pattern calls for cotton twill tape. Joann’s, to my understanding, only has polyester twill tape in stock. That’s a compromise I am willing to make for the sake of color matching, if at all possible. Second is the construction method. The lockstitch sewing machine, meaning a sewing machine that uses an interlocking upper and lower thread to create its stitching, was invented in 1846. The home sewing machine came into being in the late 1880s, into the early 1890s, and electric sewing machines in 1899 (Singer). It wouldn’t be that anachronistic to use my 2023 Singer machine in this project, however, the pattern doesn’t mention a sewing machine at all. The phrasing used for attaching that step is:

“Baste the two strips together, bind both ends with braid, and turn them up to make 2 pockets, 6 inches deep. Sew up the sides and bind all around with braid.” (198).

So, it could go either way. Questions are:

Machine or hand sew?

If hand sewn, running stitch or back stitch, because it will be bound over with braid?

Do I bind on the braid with a slightly weaker, waxed cotton thread, or do I stick to the all-purpose polyester?

I decided to hand sew everything, with waxed cotton thread – and I was able to find cotton binding braid!

Such research rabbit holes were not uncommon in my creation process. Starting with the scarf pattern, the experience of making led me to continue with patterns from Knitting and Sewing instead of moving on to another book also led me to me research fiber trade routes, aniline dyes, and early 20th century legislation that impacted textile trade and material access. Nearly a month into the semester, I realized I had made the fatal mistake of thinking I could make the whole scarf pattern from a single skein of yarn. While I can make a scarf from one skein of yarn, this specific pattern for a scarf that measures ten inches wide, and six feet long is solidly not that type of scarf. The two skeins of yarn I used, while theoretically the same color, weren’t from the same dye lot.

At least to my perception of the final product, there’s a pretty distinct difference in color, bisecting the scarf. While sorting out my thoughts in my research journal, a few points of interest, as follows, came up as the frustration turned to curiosity:

While I’ve often heard the phrase “piecing is period” in reference to piecing scrap fabric, or offcuts to fit the needs of a sewing pattern, and I know that wool, silk, and other fibers were rationed during the first world war, which lead to the rising of hemlines in dresses and the simplifying of fashionable silhouettes, at that point of researching and still now, I haven’t been able to find any mention of a yarn shortage in the US or UK extent newspapers or magazines. In the introduction to Knitting and Sewing: How to Make Seventy Useful Articles for Men in the Army and Navy, there’s a discussion of disruption of trade routes and a conversion chart between British and American materials with the expectation that American readers wouldn’t be able to get British yarns. That issue was twofold, though, in that American fiber stores didn’t regularly stock international goods, across the nation, as they do now. So not only was there a possible fiber shortage – or at the very least a synthetic shortage due to maritime warfare impacting shipping – but Americans in port cities or major metropolitan areas were the ones to be likely to have access to British-made materials, a population which did not include most Americans. All of that was to say that it may be accurate to have distinct color variation between skeins of yarn used on a single project. That, and others probably made the exact same mistake I did.

I found tangentially related, but deeply interesting information on World War I dye shortages from the following website: https://americanhistory.si.edu/explore/stories/new-vogue-black-and-white-during-world-war-i-dye-shortages.

Knitting and sewing; how to make seventy useful articles for men in the army and navy was published September 16, 1918, after the November 1917 “Trading with the Enemy Act” (Shaw) that allowed American companies to steal patented manufacturing techniques and formulas, from companies in countries with whom the USA was at war, and use them to manufacture things on the home front. This included synthetic dyes for which Germany was the main manufacturer up until that point.

Future Plans

I plan to continue making patterns from Knitting and Sewing: How to Make Seventy Useful Articles for Men in the Army and Navy, and possibly try my hand at some techniques from other books. What follows is a list of the patterns I’m still interested in trying to make and some techniques I didn’t get to try, that I want to highlight:

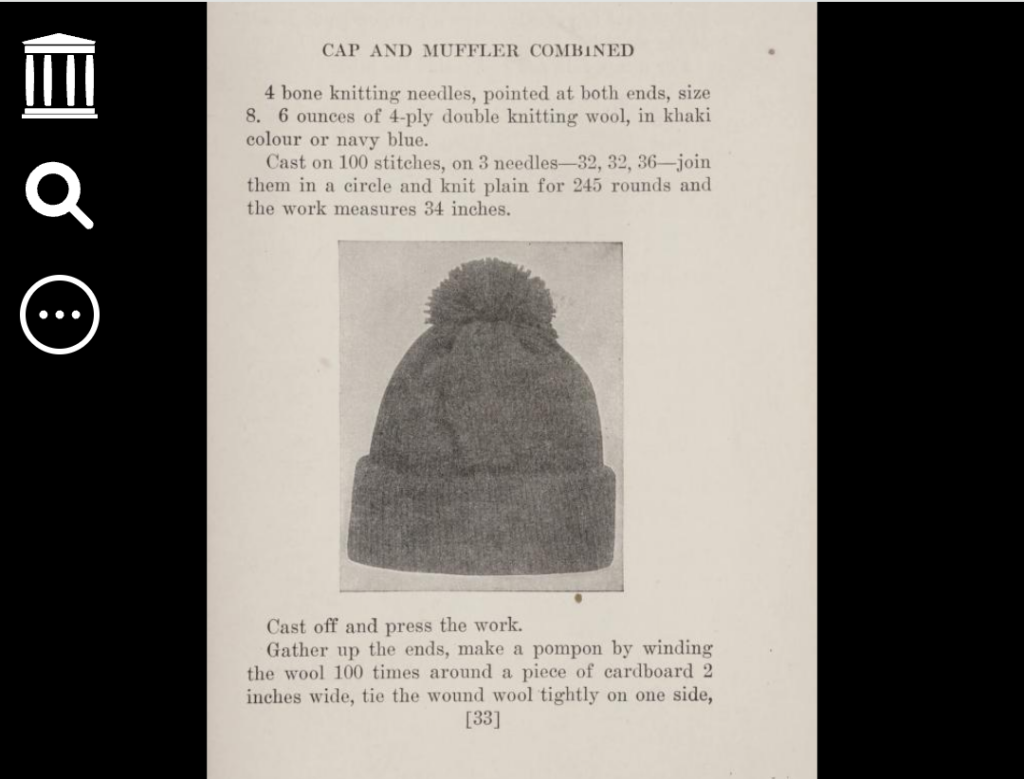

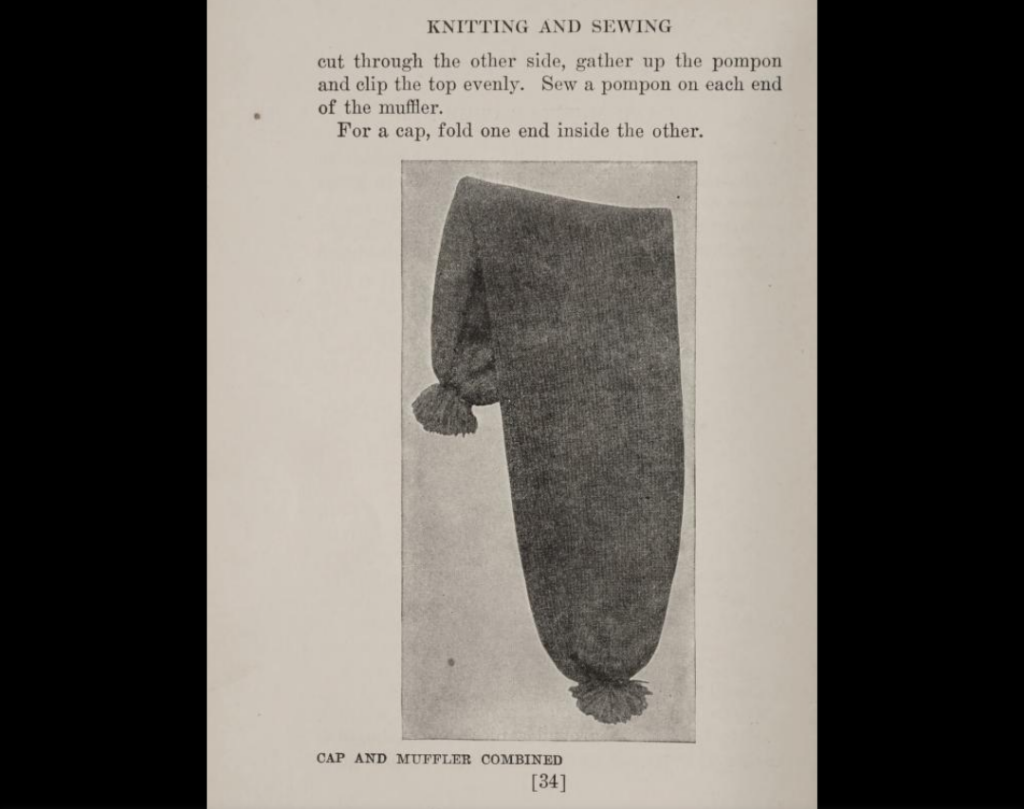

- “Skull Cap” from Knitting and Sewing: How to Make Seventy Useful Articles for Men in the Army and Navy (p. 32)

- “Knit muffler in cardigan stitch” from Knitting and Sewing: How to Make Seventy Useful Articles for Men in the Army and Navy (p. 40)

- “Knit muffler in diagonal stitch” from Knitting and Sewing: How to Make Seventy Useful Articles for Men in the Army and Navy (p. 41)

- “Plain Jersey (for 36-40-inch chest)” from Knitting and Sewing: How to Make Seventy Useful Articles for Men in the Army and Navy (p. 97-98)

This might be a bit too much to succeed in making, but I’m invested in the prospect of trying. - “Bed Socks” from Knitting and Sewing: How to Make Seventy Useful Articles for Men in the Army and Navy (p. 165-166)

- “Forecastle Book Bag” from Knitting and Sewing: How to Make Seventy Useful Articles for Men in the Army and Navy (p. 196-197)

- The darned net patterns/techniques from The Art of Modern Lace-Making (1896)

They seem like an accessible entry into historical lace-making practices. The advice above the example photo notes that the “points of the flounce are darned back and forth in selvedge effect; but they may be worked in button-hole stitch if preferred.” With the passing of time between the writing of the pattern and me as a twenty-first century reader, I don’t really know what that means beyond using thread to try to make the raw edge of the net resemble the finished, selvedge edge of woven fabric, and I can’t quite see clearly enough in the photo to know more detail than that. But that will make future experimentation more fun! - Dyeing wool, following the instructions from Notes on Spinning and Dyeing Wool.

- Modeling crochet lace patterns after the examples in The ladies’ hand book of fancy and ornamental work, comprising directions and patterns for working in applique, bead work, braiding, canvas work, knitting, netting, tatting, worsted work, quilting, patchwork, etc. (p. 102-110)

References

Singer, “History,” accessed October 9, 2024. https://www.singer.com.tr/en/corporate/history.