By Alex Rienerth, ’25, MA in Literary History, 2024-2025 Graduate Assistant in Rare Books

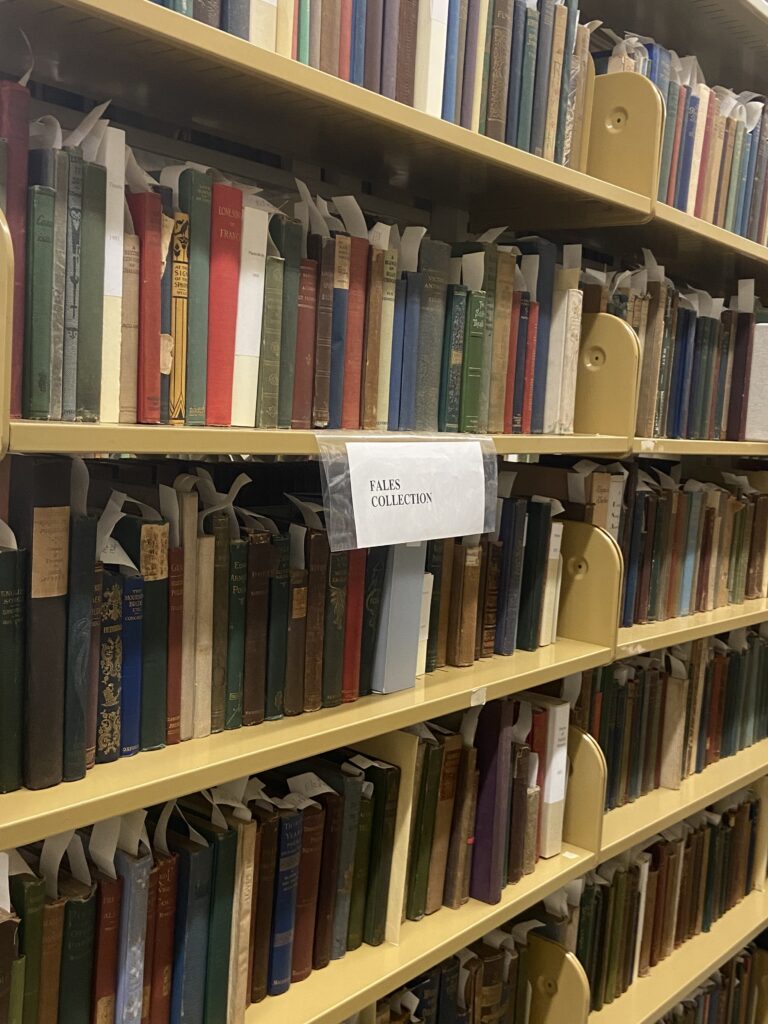

The Edward C. Fales collection was a bit of a mystery to me when I started working with it last semester. Many of the collections in rare books are extensively documented, including records from collectors that express their motivations and intentions (e.g. the Morgan Collection in the History of Chemistry), or otherwise have apparent commonalities among their individual holdings (e.g. Author Collections). Fales is a little more difficult to pin down: where did these books come from? Why are they organized this way?

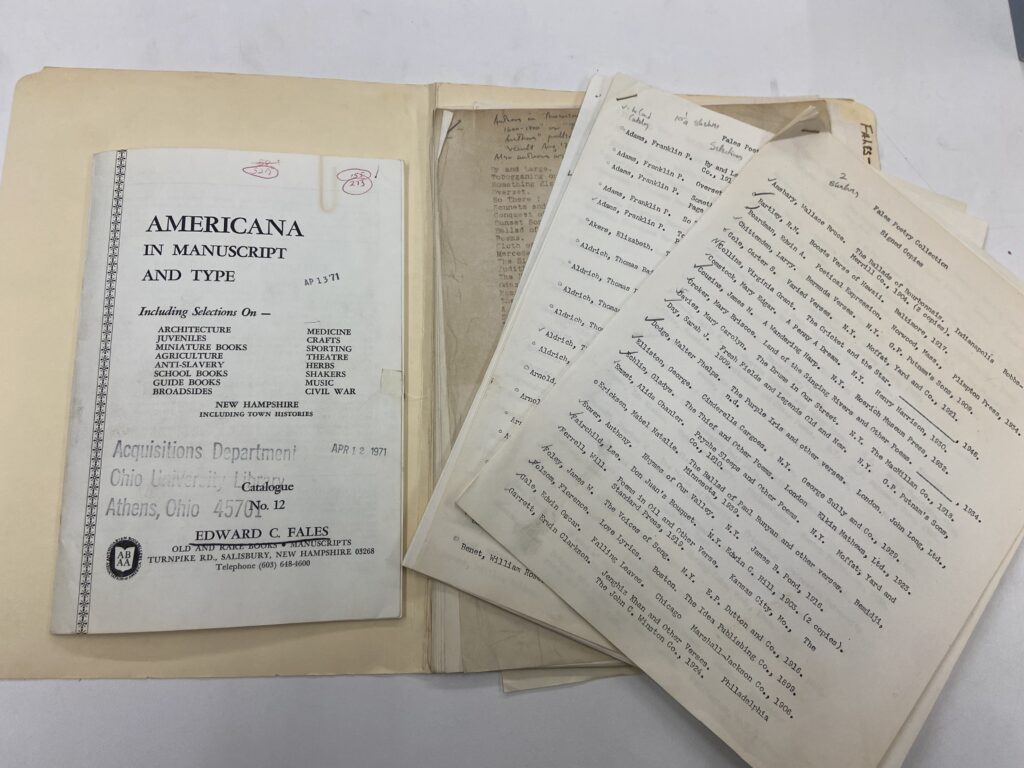

To start, Archives & Special Collections received the books for the Fales collection in fall 1971 from—you guessed it—Edward Fales, a rare book dealer from New Hampshire. There isn’t a lot of information on Fales, either online or in our records. According to the New Hampshire Historical society, of which he seems to have been an active member in his lifetime, Fales specialized in Shaker materials and spent at least 24 years in the book dealing business.

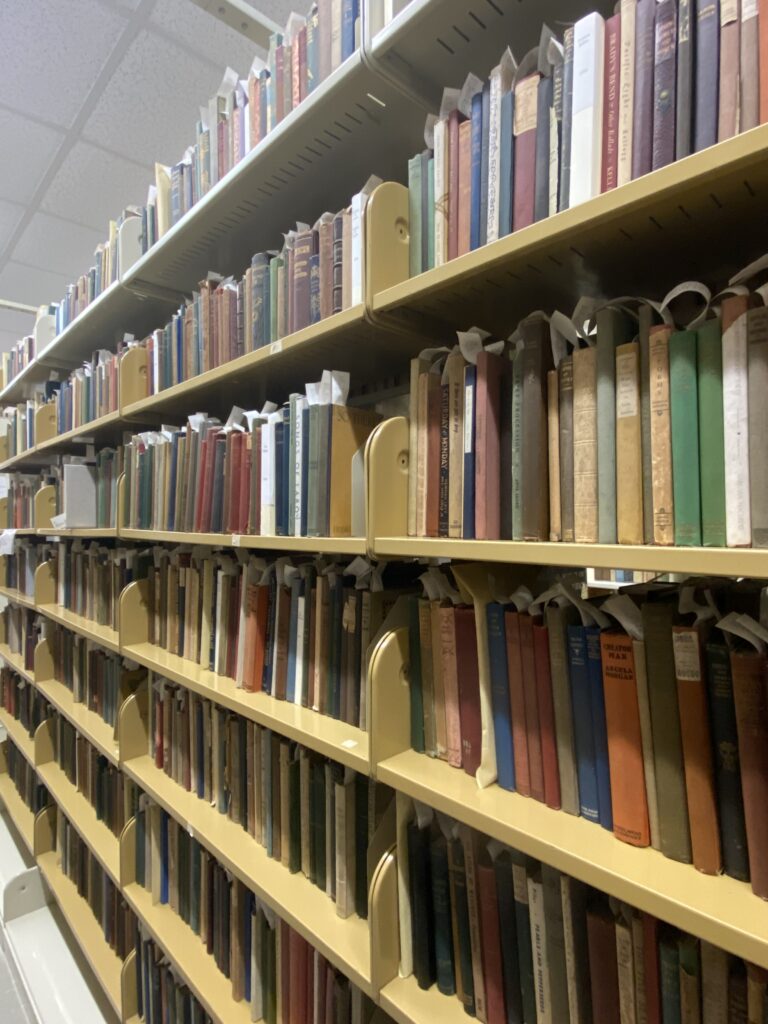

Otherwise, a lot of our clues for the bookseller come from the Fales file, detailing the libraries’ acquisition of the collection. The file includes a bookseller’s catalogue, three typed lists of books, and a series of letters between Edward Fales and a previous head of the library’s special collections, Richard W. Ryan. First, this kind of record-keeping helps keep track of invoices and ensure that we actually have all the books promised by the seller. For my purposes, though, this gives some context on how and why we acquired this collection. In one of his letters to Fales, Ryan notes the collections’ value to OHIO in its diversity (by this, I think he meant “sheer number”) of authors and for covering a period he felt rare books was lacking: American texts from 1840 to 1940. (This alone speaks to how much our rare books collection has changed since then!)

The booksellers’ catalogue, Americana in Manuscript and Type, bears the name and address of Fales’ business, and we find the description of our collection on its first page: a listing under the title “Poetry Collection” for “some 1300 volumes from the library of a collector of first editions covering a large variety of authors.” Notes in the margins indicate phone conversations between the writer (Ryan?) and the bookseller (Fales).

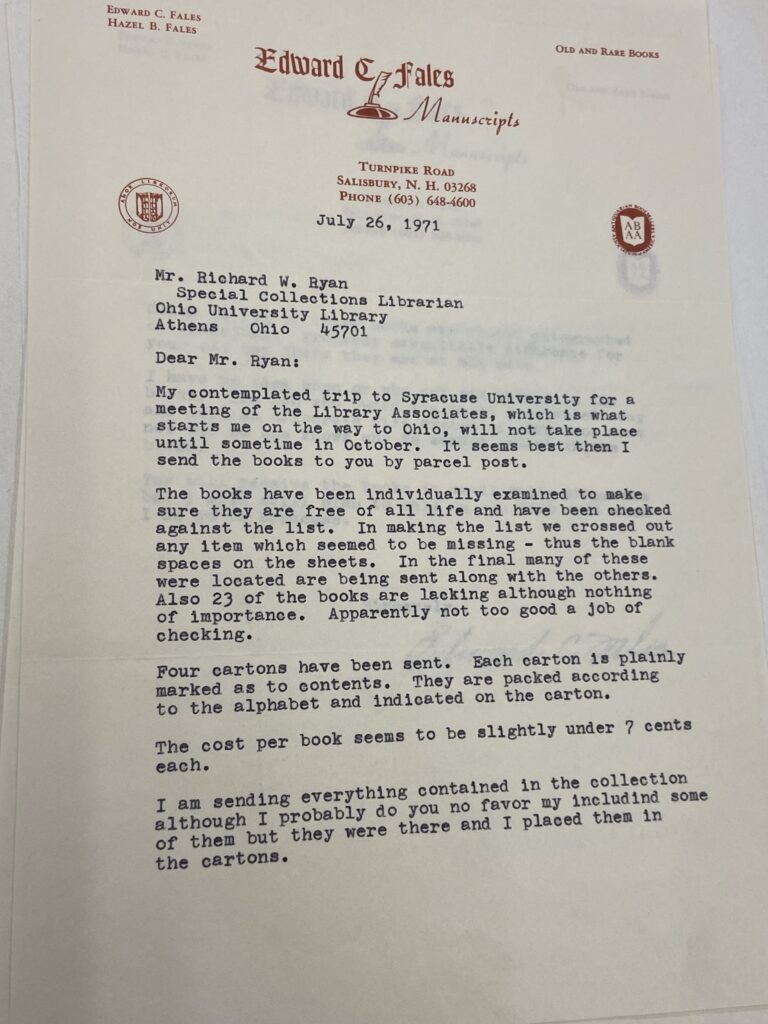

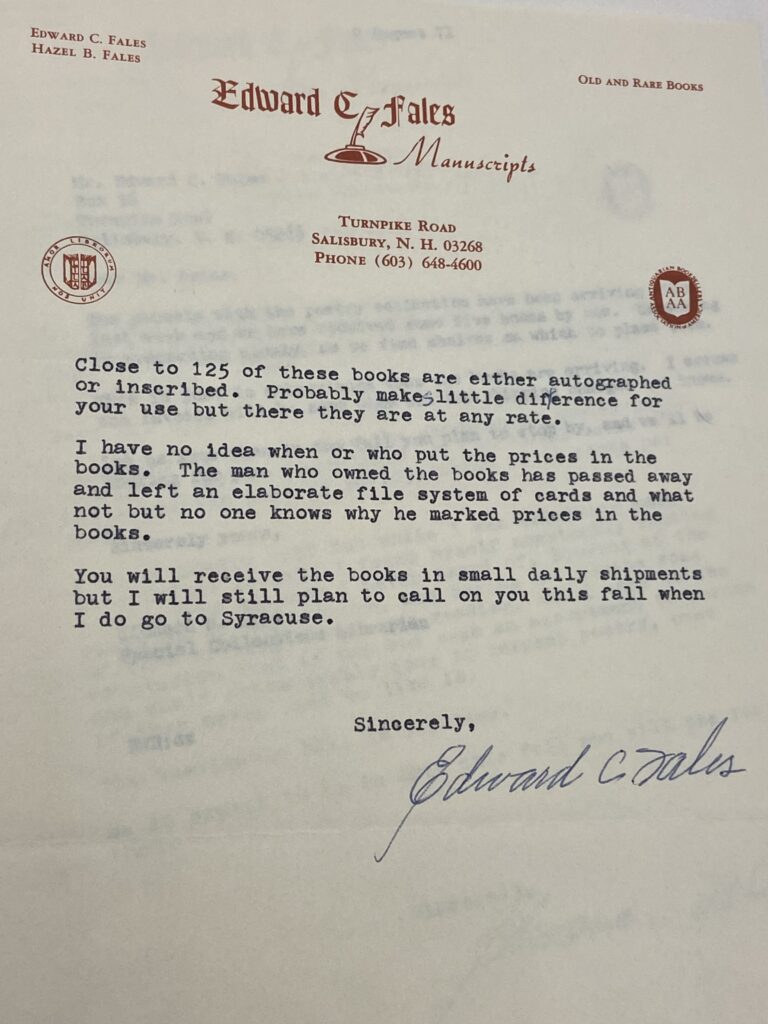

What interests me here is that, compared to the Edmund Blunden and Morgan collections, named directly after the people who curated and organized these holdings, the “Edward C. Fales Collection” is kind of a misnomer. Fales did acquire them, somehow, from the original curator, but was not the collector himself. As he explains in a letter: “[the original owner] has passed away and left an elaborate file system of cards and what not but no one knows why he marked prices in the books.” So, either he bought them directly from that original owner or received them (by purchase or otherwise) from whoever inherited these volumes.

When I read that there was “an elaborate file system of cards and what not,” what I’m guessing corresponds to some original organizational structure, I was pretty taken aback! I’m not going to pretend that access to this filing system would’ve magically communicated what the collector was thinking. More than likely, it would’ve been more confusing to me than for Fales. Still, having access to records like these helps us start to imagine what these books meant to their collector: the fact they had an “elaborate” system tells me there was some meaning they gave to these materials.

In the same letter, Fales writes that before sending them to OHIO, “the books have been individually examined to make sure they are free of all life and have been checked against the list.” Of course, he’s discussing a very necessary process of making sure no bugs or mold have gotten into the book, but it’s vague enough that there’s a bit of irony there; however attached the people who owned them before were to these books, their presence is more or less deliberately removed (save for library stickers), the penciled-in price on the cover, and the authorial inscriptions in many of our copies.

Despite the relative lack (or loss) of context for the Fales collection, we can still evaluate what we have and make some guesses on how to understand these materials as a composite whole.

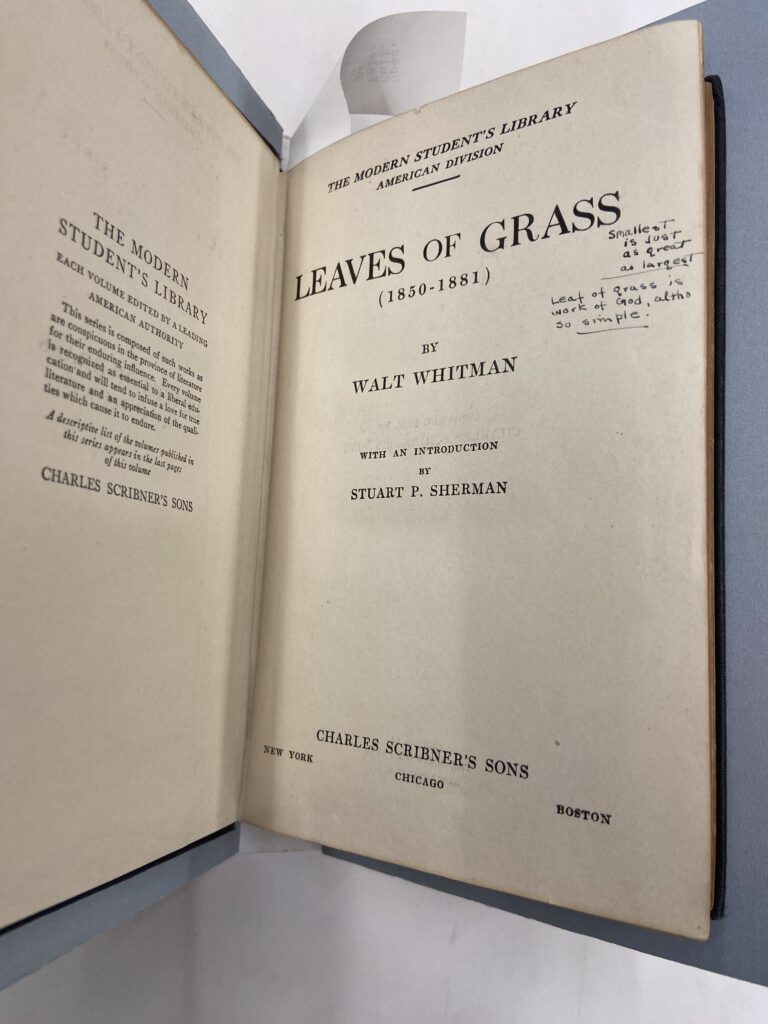

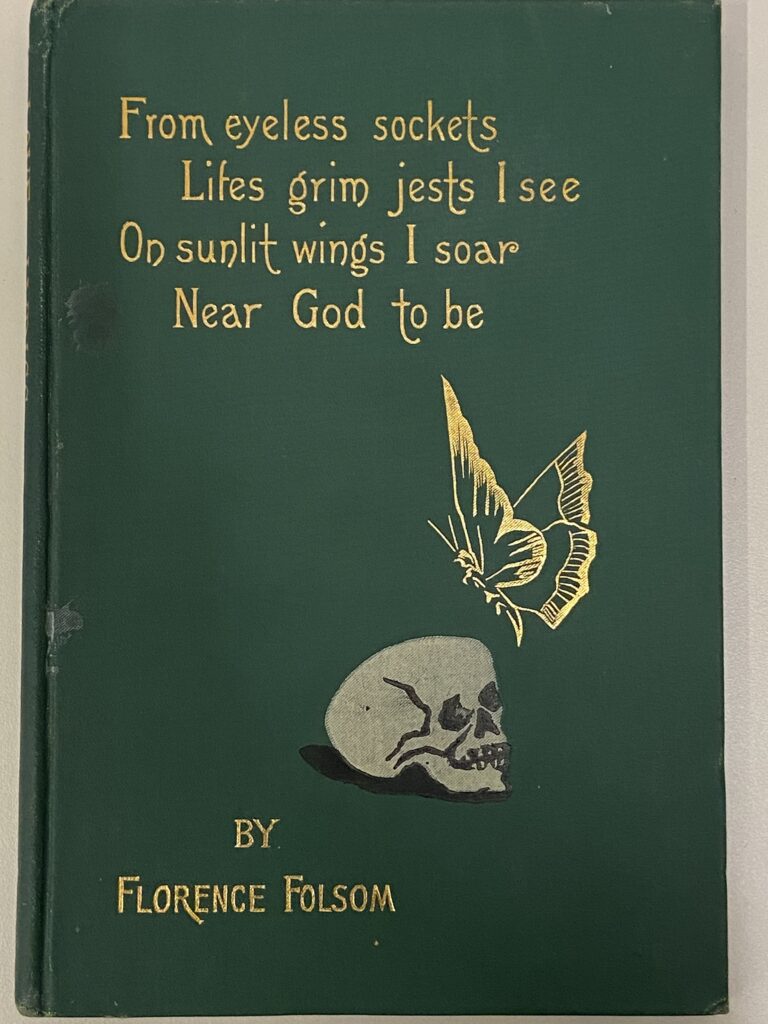

After browsing through the collection, Fales’ decision to advertise this group of books in a catalogue of Americana makes a lot of sense. The collection includes well-known American writers like Walt Whitman, but most of the books come from authors who aren’t as well known today. Still, it’s usually best to maintain some skepticism when trying to categorize a collection as one thing or totally representative of a place/time. For example, even as these rarer, lesser-known poets might provide perspectives we don’t always get from a history textbook (or a late-night Wikipedia deep dive) this is still a collection curated by someone (even if we don’t know who), then acquired by another person who made a decision to label these books (and sell them) as “Americana.” What does that imply?

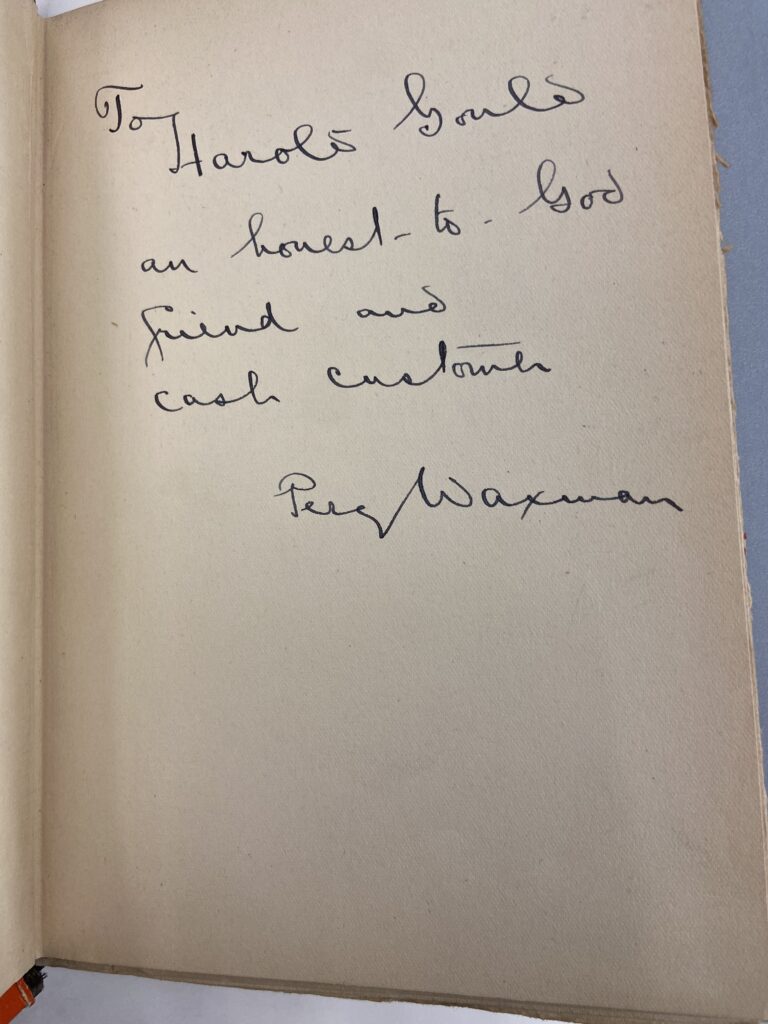

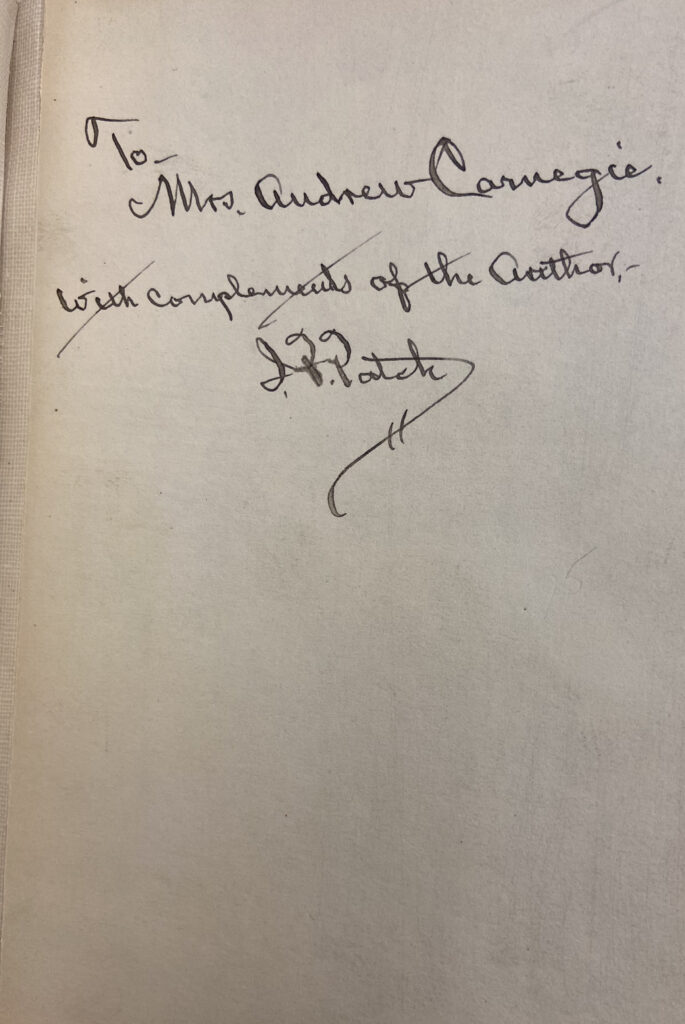

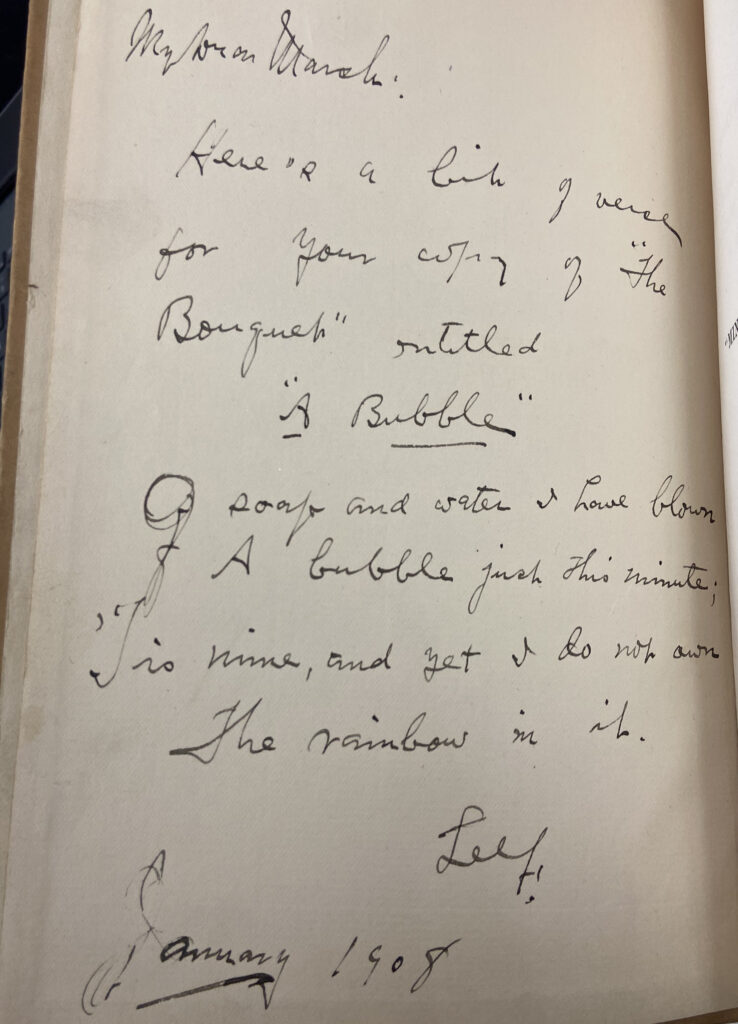

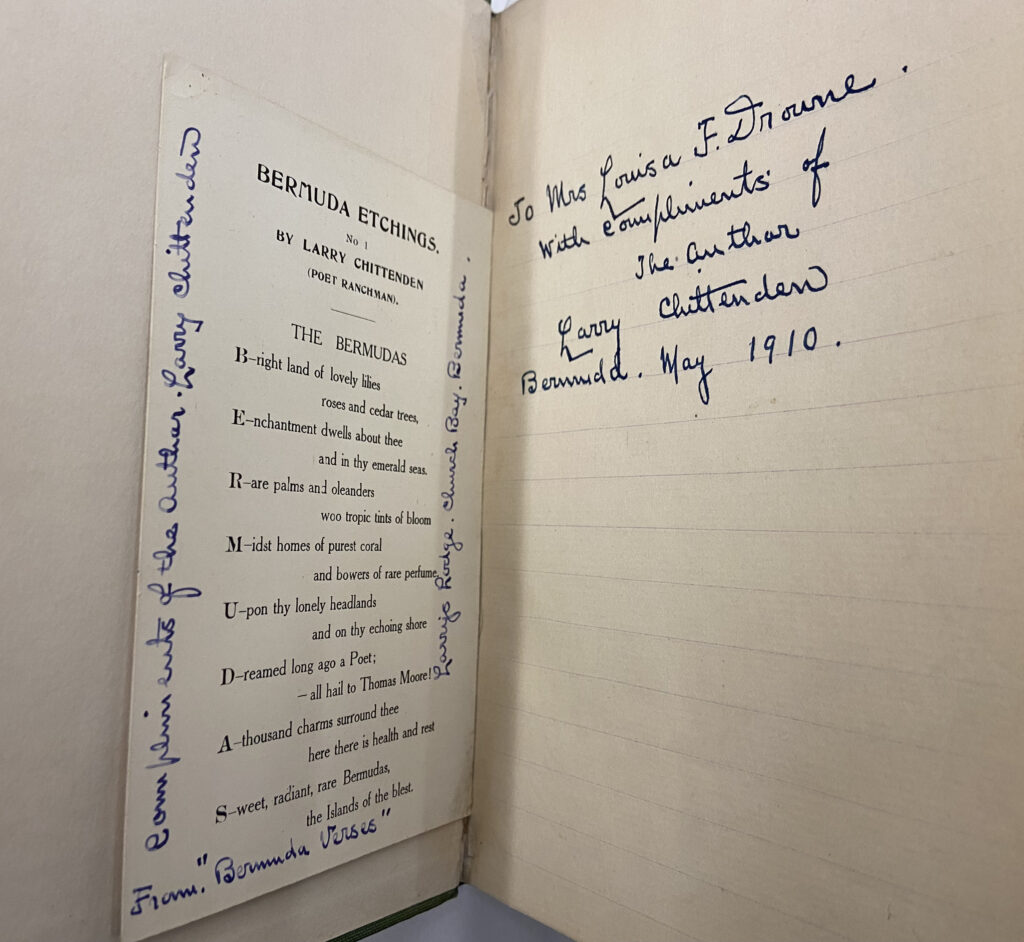

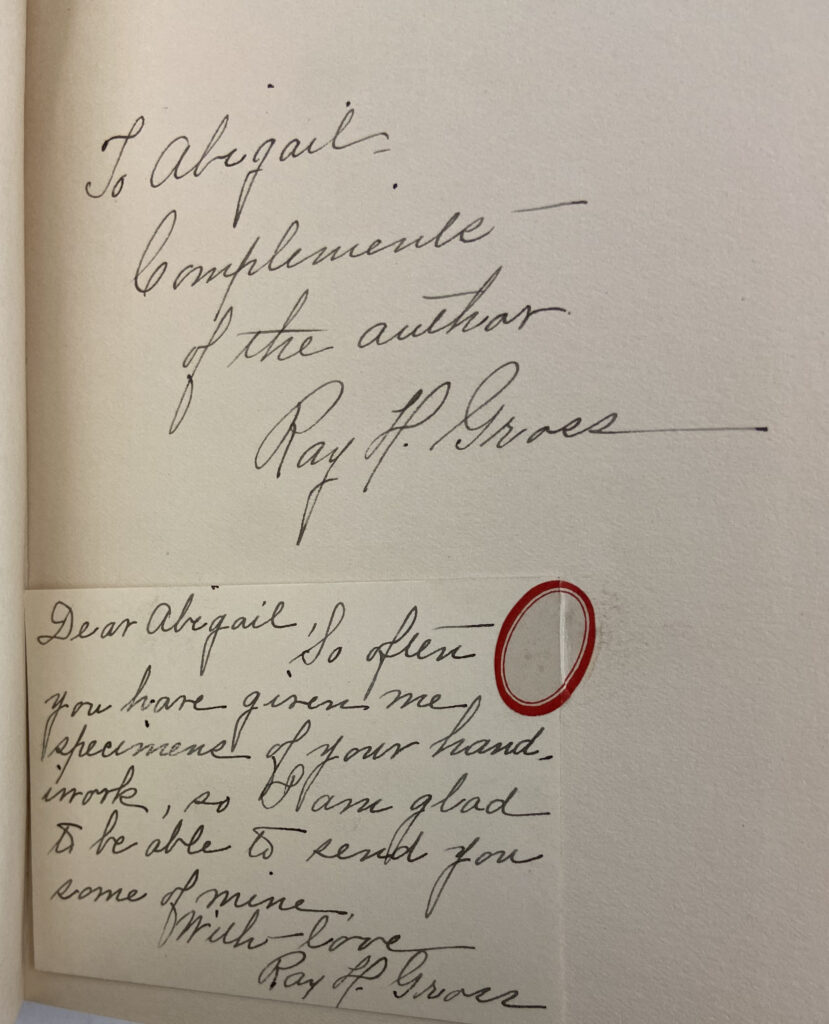

Reading poems from these authors, and, as a special (and relatively frequent!) feature of our collection, seeing some of the inscriptions to people in their social circles could broaden our sense of day-to-day life in the 19th and early 20th centuries, especially when we tend to feel distant from this time period. It’s always wise to remember that these authors don’t speak for everyone’s day-to-day across the times and spaces covered by these collections, but instead, we can think of the texts as pieces of a much larger/more complicated amalgamation of lived experiences in time. Basically, rather than a universal “Americana,” these volumes can serve as specific, personal pieces from people whose lives we otherwise may not have been aware of.

![Inscription inside Violet Rays by Olive Allen Robertson (“To Katherine Because of Memories Olive Allen Robertson ‘To have friends who are such because of the love and common interests which enrich our relationsips[sic] with life, and (???) life through mutual give and take Hartford Conn. 1906”](https://sites.ohio.edu/library-archives-blog/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/IMG_7582-768x1024.jpeg)

Since my work in the Fales Collection included checking the list of autographed copies found in the file against the books on the shelf, I got to see countless notes that told me something about the social lives of these authors. Granted, some of the copies are signed and numbered without any type of note—cool to see, regardless—but many include everything from thank you notes to patrons and business partners, holiday greetings to family members, expressions of admiration to politicians/public figures, and warm words to friends.

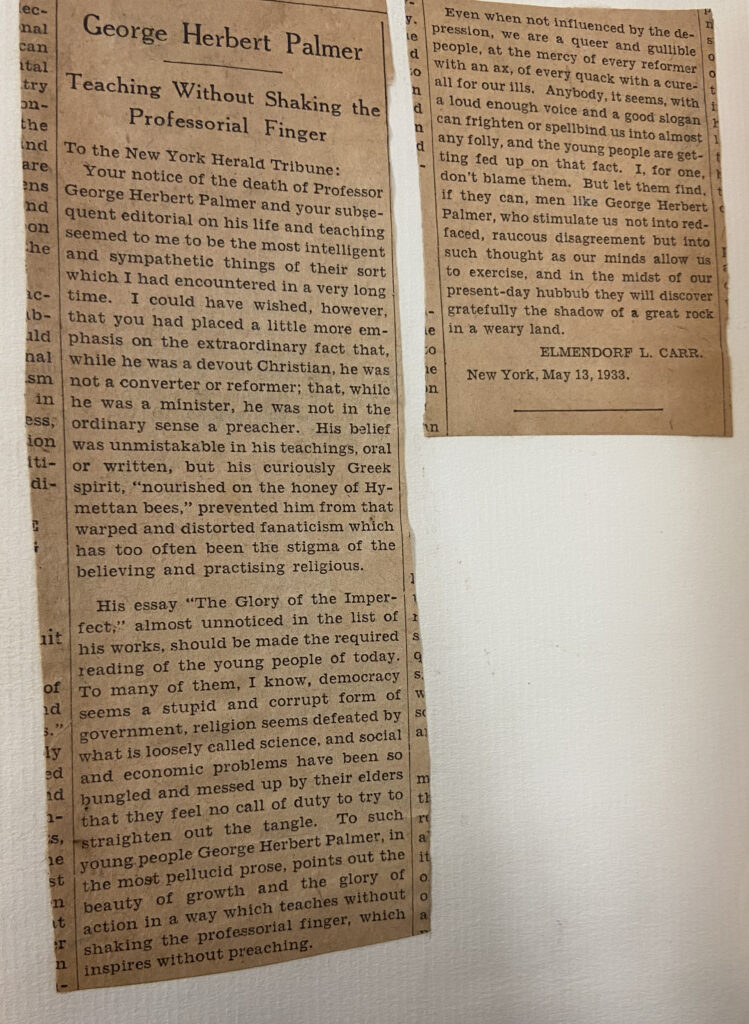

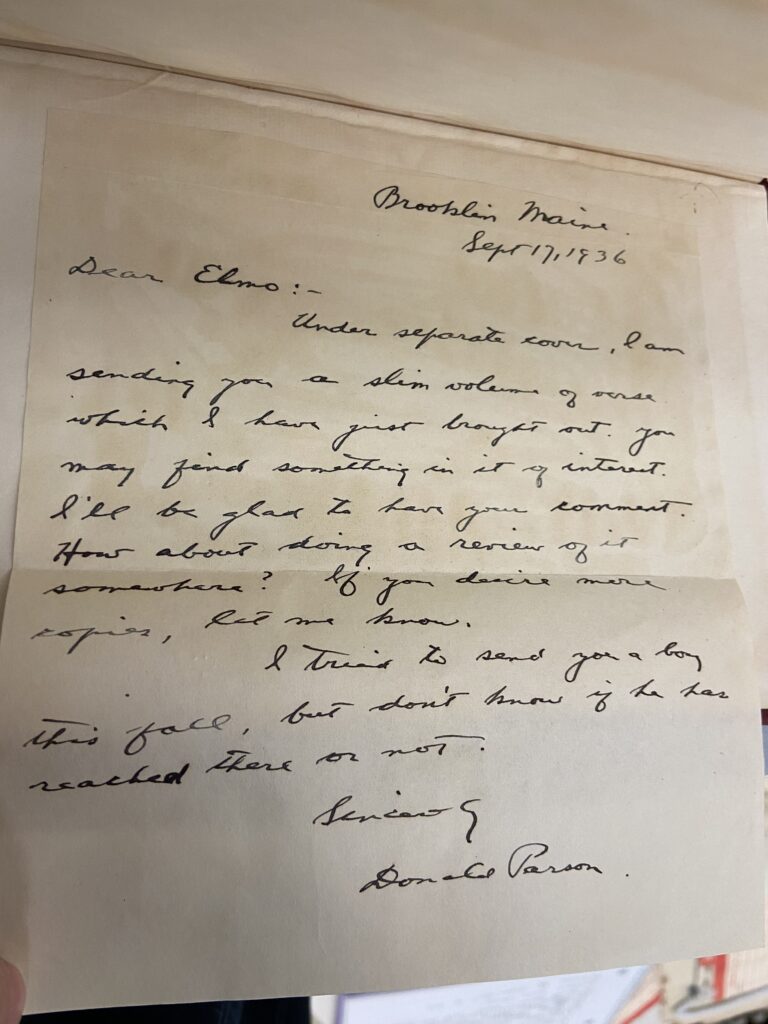

Some of the relationships were harder to discern, like in Donald Parson’s Glass Flowers which includes a letter from Parson asking E.L. Carr, a critic, to review his book—the review is even pasted into the book! It’s difficult to say whether they were friends before the review, became acquainted after the fact, or if the relationship was all business. Pasting a review in a book and keeping the author’s solicitation letter seems to me like keeping one’s receipt after a transaction, but then again, Parson refers to him as “Elmo” in his letter (but E.L. Carr in the inscription?).

![Review by Elmendorf L. Carr of Parson’s Glass Flowers pasted inside the front cover; it is a relatively positive review, despite Carr’s note that “[it] is not great poetry.” A little back-handed, huh?](https://sites.ohio.edu/library-archives-blog/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/IMG_7589-1024x887.jpeg)

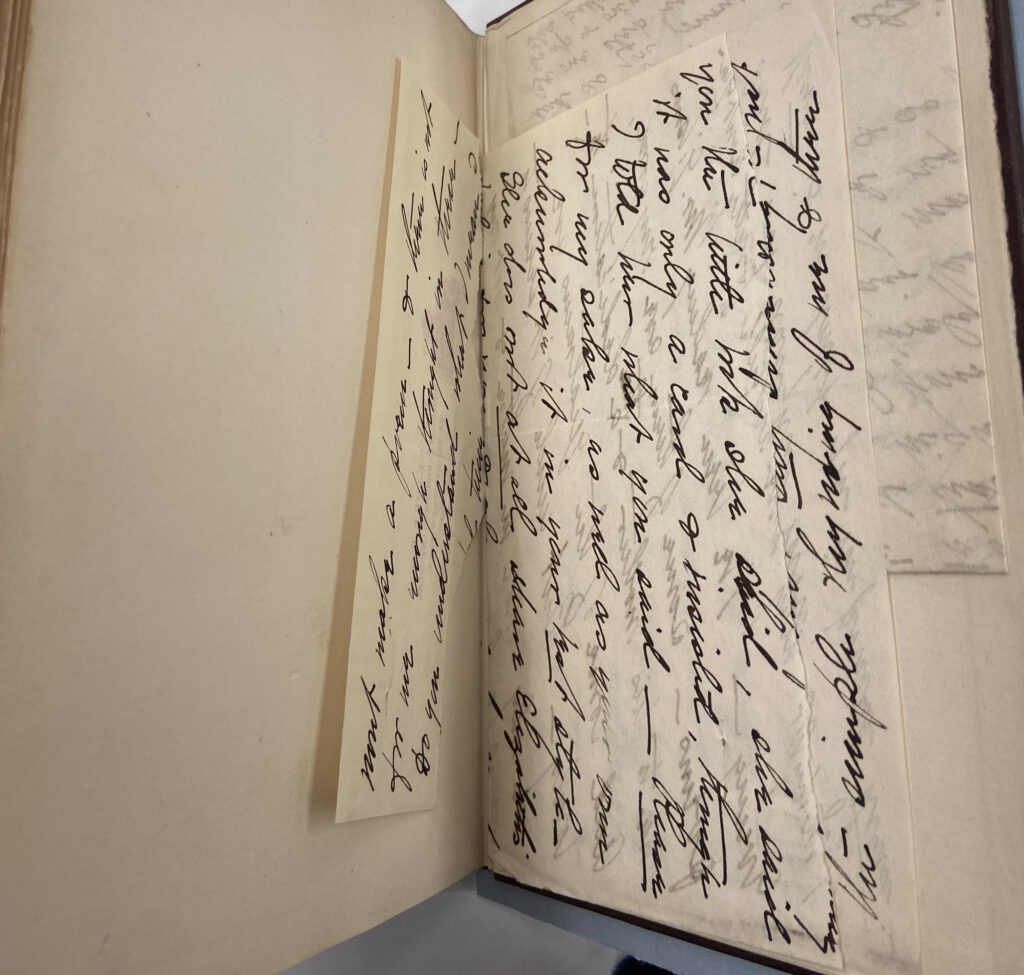

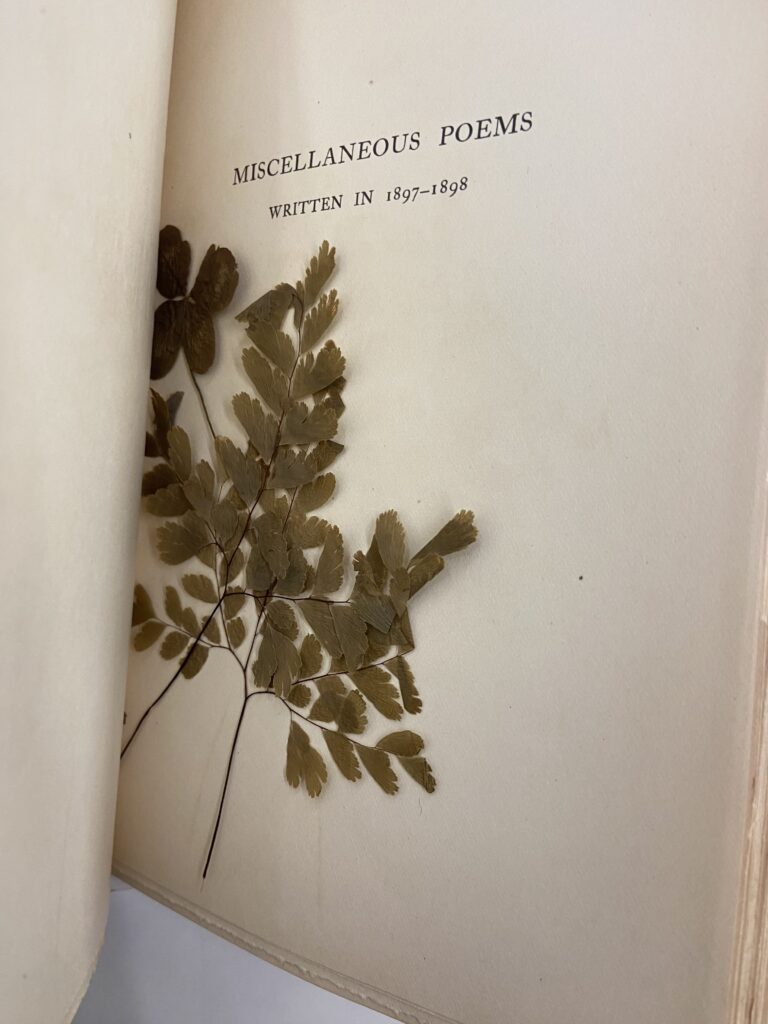

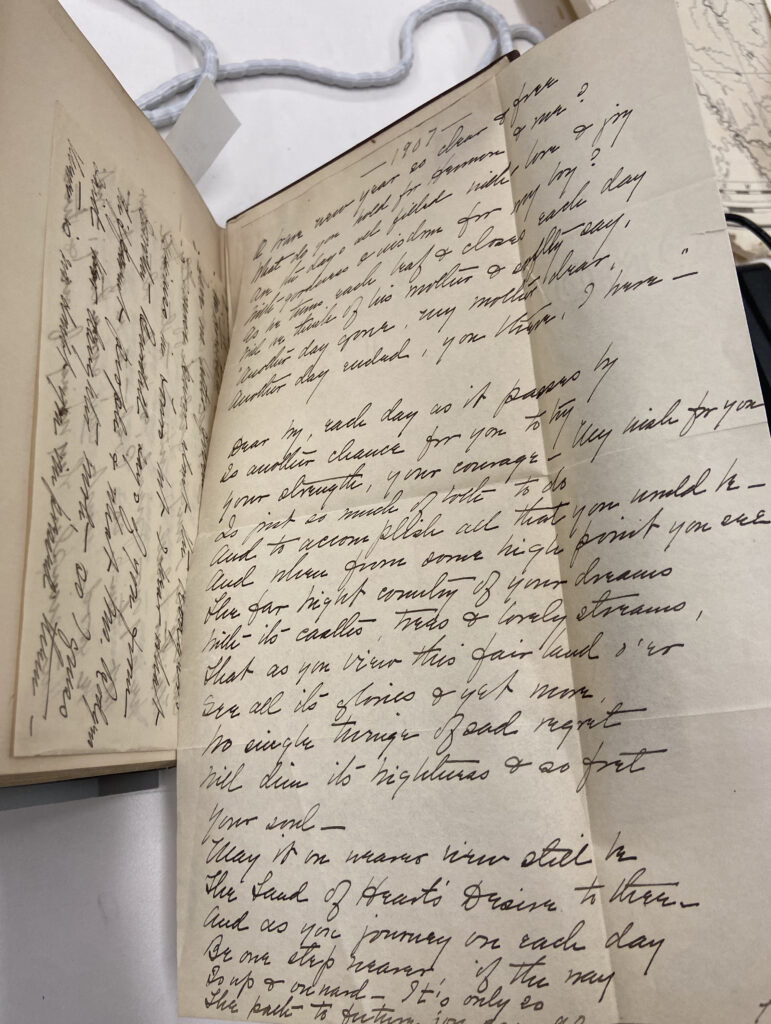

Thinking back to Fales making sure the copies were “free of life,” that wasn’t quite the case for Charles Gibson’s The Spirit of Love. I was drawn to the book by the gold-stamped flowers and gilded pages. Then, while paging through the book, I found pressed plants—an incredibly pleasant surprise! To add to this good luck, I found two letters along the back cover (likely sent to Herman Milton Hubbard Jr., one of the previous owners of the book, from his mother, Susan Platt Hubbard, an anti-suffrage activist…) one, tipped in (what seems to be a new years’ well-wishes note) and the other with some rather critical words concerning Gibson’s poetic abilities!

Thanks to the extensive work done by historians on The Gibson House Blog, it seems clear that Gibson had relationships with men, evidenced by a retrospective dive into his life and writing. I can’t help but wonder how this impacts, among many things, the left-over pressed plants in this volume and Platt Hubbard’s less-than-favorable view of his poetry (whether from not picking up the double-meaning in the coded language, or alternatively, picking up on it and not quite being pleased with it…though, maybe the poetry’s just bad. I’m not one to judge that). My questions and curiosities here are, frankly, endless.

I think it’s in the kind of rabbit holes you fall into where this collection shines the most as a cohesive unit. Many of these authors aren’t necessarily the ones we’ll be taught in an Introduction to American Literature course or even see re-posted in graphic form on someone’s Instagram story, but there are some real hidden gems here, and more than that, a collection of fascinating, rich, sometimes interconnected, and always complicated histories.