By Jadyn Carpenter, Communications Studies ’25, for JOUR 4130 Gender, Race, and Class in Journalism and Mass Media with Victoria LaPoe, Spring 2025

During the spring 2025 semester, the staff of the Mahn Center for Archives and Special Collections worked intensively with Victoria La Poe’s JOUR 4130 class, Gender, Race, and Class in Journalism and Mass Media. The students explored, selected, and researched materials from the collections, then worked in small groups to prepare presentations. The students had the option to then expand their research into a blog post like this one for their final project.

Civil Rights Coverage

Papers from the Ohio University Presidential archives and published student newspaper reports indicate that Ohio University’s 15th President, Vernon R. Alden (1962-1969), promoted the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, supporting Black rights and equality at Ohio University and beyond. Alden met with Black activists, spoke to the injustices facing Black students, and used his platform in his attempts to educate and uplift those around him. This understanding is illustrated very well by The Post which was the campus’s major student newspaper throughout Alden’s term as OU’s president.

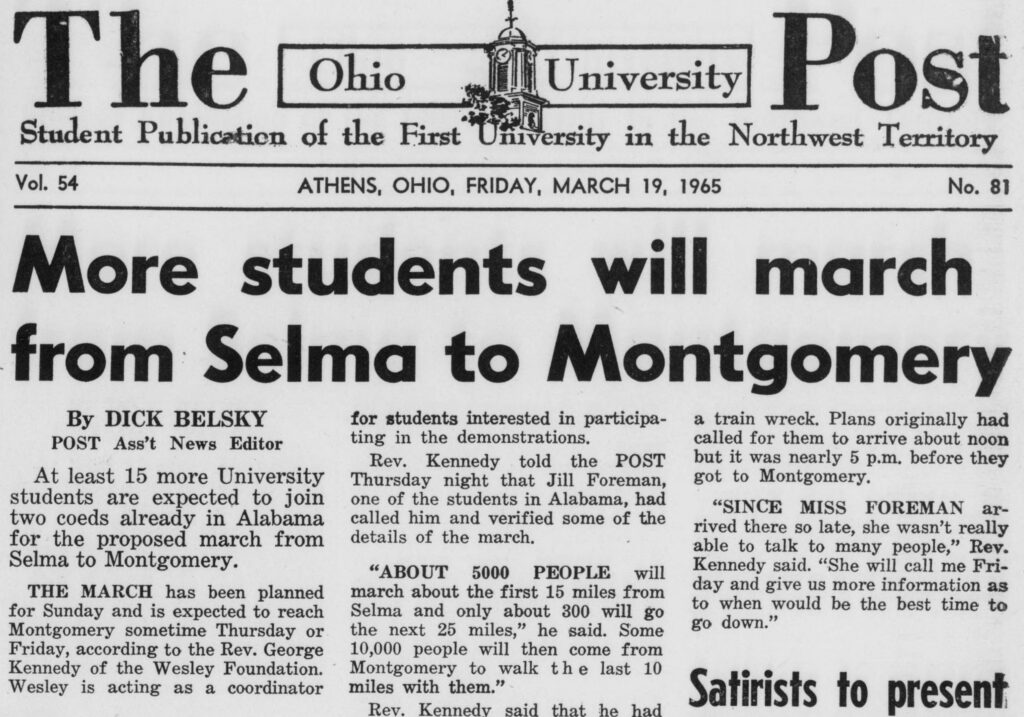

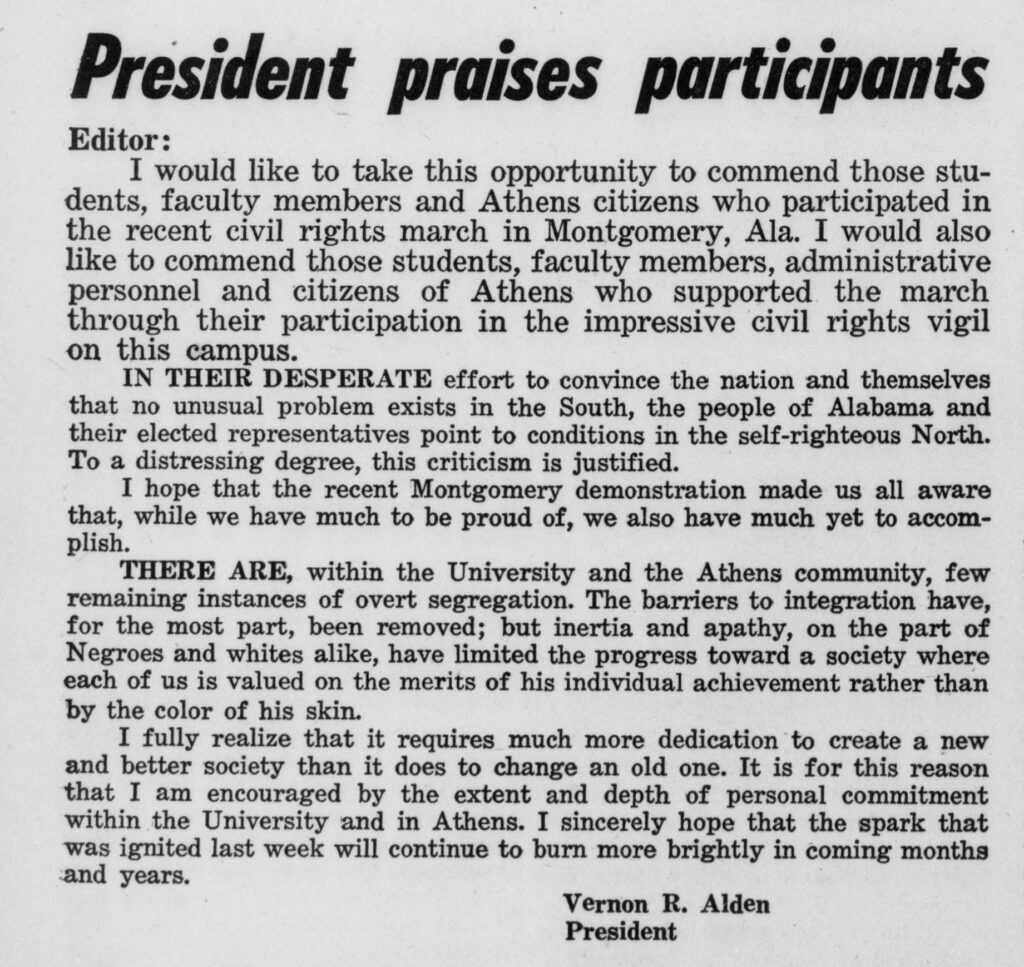

In March of 1965, when thousands of people marched with Martin Luther King Jr from Selma to Montgomery, many students from Ohio University joined the cause. Risking backlash from some of OU’s stakeholders and from the general public, President Alden quickly and openly applauded the students, praising them for their involvement in Civil Rights matters. From this point on The Post covered national events relating to Civil Rights often by focusing on the movement through the lens of President Alden. This instilled the idea that the racial climate was a progressively regarded issue on campus, at least from the perspective of The Post and the President (Bennet, 2016).

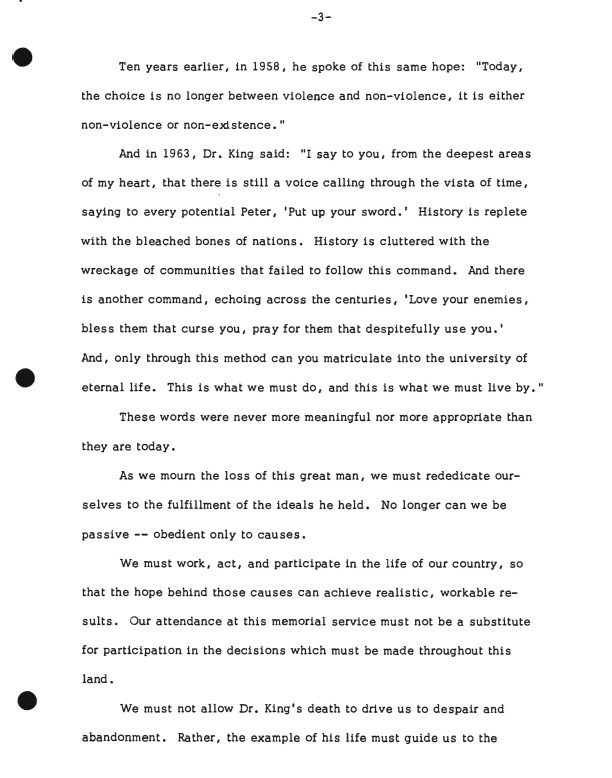

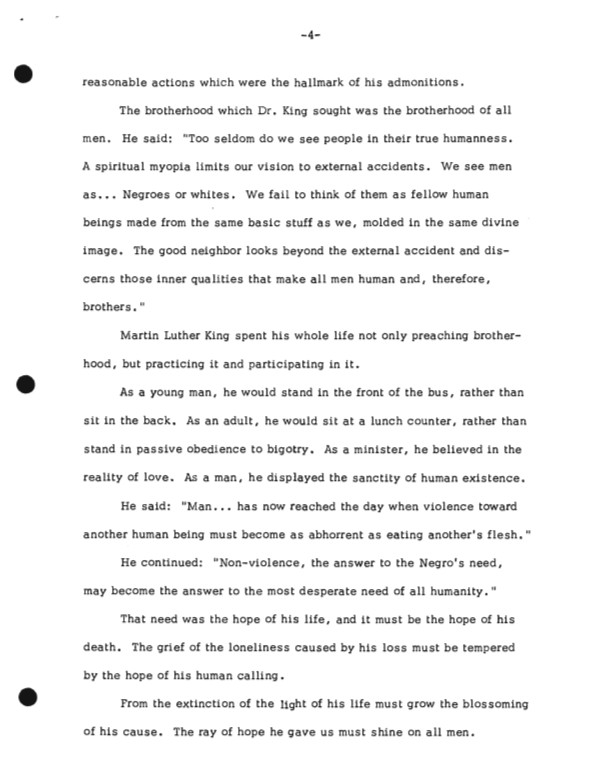

For example, in spring 1968, following the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. understanding and acknowledging the importance of Dr. King and of this moment in history, President Alden ordered the cancelation of classes for the day and delivered a powerful, detailed eulogy to the OU community.

Alden stated,

“As we mourn the loss of this great man, we must rededicate ourselves to the fulfillment of the ideals he held. No longer can we be passive—obedient only to causes.” (Alden, “Eulogy,” April 7, 1968, p. 4).

He continues by saying,

“From the extinction of the light of his life must grow the blossoming of his cause. The ray of hope he gave us must shine on all men.” (Alden, “Eulogy,” April 7, 1968, p. 5).

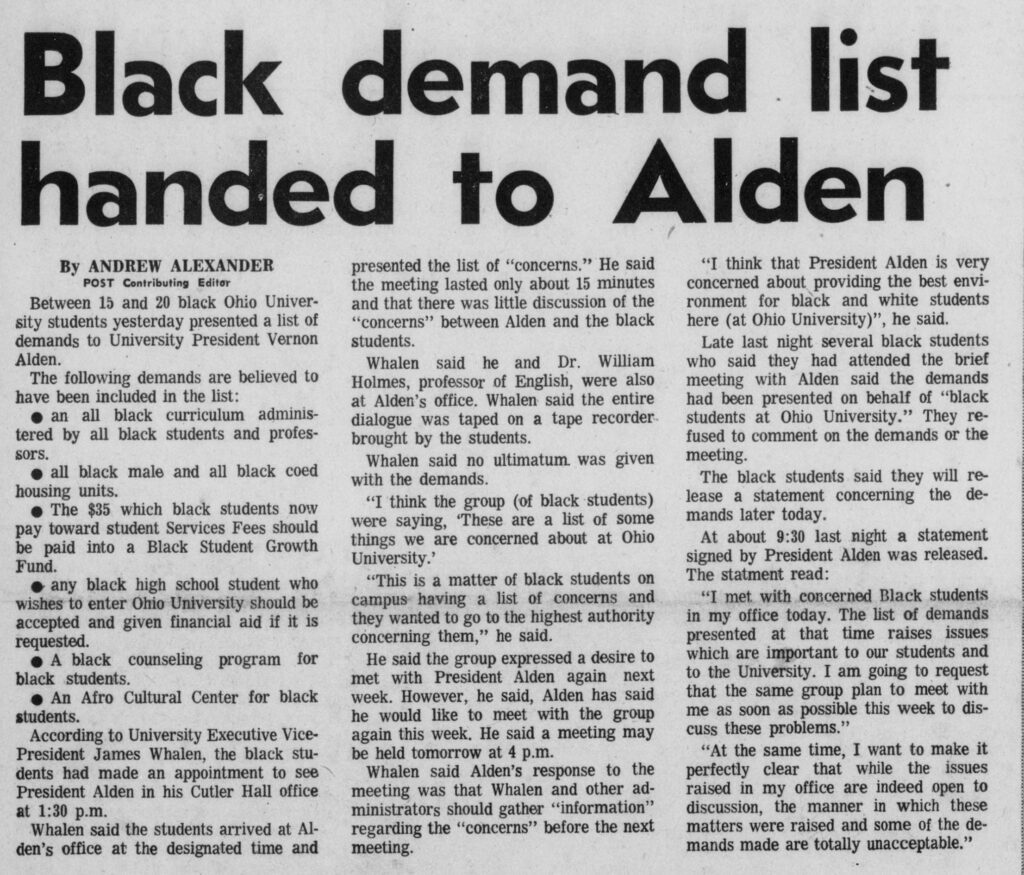

In December of the same year, 1968, The Post covered an instance when a group of Black students handed Alden a list of demands for changes to be made in OU’s culture and curriculum. We know that Alden’s effort towards reducing racism on campus was very well documented by The Post, which considered itself to be a neutral force; often in its pages providing constructive criticism to those who diverged from fairness and equality (Whitten-Woodring, 2009). However, it should be noted that since responses from Black students were often lacking in The Post narrative, at least one side of the developing story was not being offered by The Post.

Breaking it Down

The efforts of both The Post and President Alden were necessary forces that helped shed light on the ongoing issue of Civil Rights in the 1960s. However, it is also important to understand how underrepresented groups tend to lose their voice in the media. Under Dr. LaPoe this semester we have delved deep into how the media often shapes the perceptions that we use in evaluating the state of the world around us. Through outside research and concepts from course material, we will explore this further.

Framing theory is the first concept that allows us to analyze the coverage of the Civil Rights Movement on campus. Through the framing of a white university president and white students, Ohio University seemed to be a very progressive and safe space for African Americans during the civil rights movement. Realistically, the mass amount of predominantly white coverage during the Civil Rights movement makes it very difficult to find any firsthand accounts by Black students, giving us no real material gauge for success or lack thereof in the eyes of OU’s Black students.

Additionally, Standpoint theory informs us that the largely white audience and student body shaped the general perception of the Civil Rights movement impressions on OU’s campus, with the media coverage covering their standpoint or perspective. This standpoint likely differs from the views of Black students at this time. While this theory originates through feminism, it is widely applicable to other marginalized groups (Helpern, 2019).

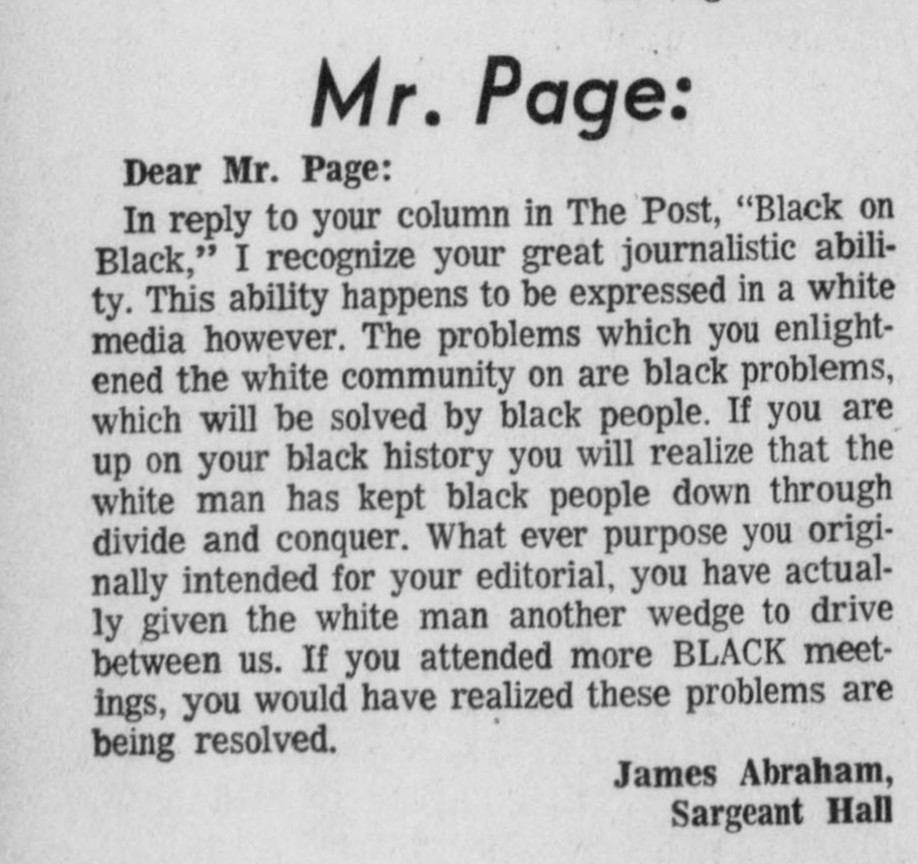

While The Post did use Resonance [OHIO login required], covering stories that held value to their audience, the lack of coverage from the Black perspective and over coverage of white support. This is cemented further in instances like seen below where a Black student wrote in response to the Mr. Page column, criticizing the performative coverage of “Black problems, which will be solved by Black people.”

Highlighting Black Voices

The Post has been the voice of students since 1939. However, as previously mentioned, it is a historically white student paper. In the wake of the Civil Rights Movement this became increasingly troubling as Black voices continued to be only heard in the background if at all. The Black Press was instrumental in providing an outlet for Black individuals to voice concerns and have their voices heard.

To better understand this, we can look to the work of Dr. Jinx Broussard and Dr. Benjamin LaPoe. In their work together they state that “a central motivation for the Black press’ formation was to correct misinformation, fill holes by providing visibility, and become a voice to the oppressed and ignored” (LaPoe & Broussard, 2018, p. 140).

However, throughout most of the 1960s, and, certainly during the Alden years at OU, there were no designated Black press outlets on campus from which we can gauge Black student perspective during the height of the Civil Rights Movement. It was not until the inclusion of a Black Studies Program in Ohio University’s academic curriculum—which was one of the demands Black students had handed to President Alden—that Black voices could be heard across campus as the Afro-American Affairs Newspaper began publishing regularly at OU.

Nevertheless, we can see that providing a platform through which Black perspectives could be published and read in the OU community was already on the minds of OU’s Black student population even before the introduction of the Black Studies Program.

This statement alone further reinforces the idea that Black students needed an outlet, free of the middleman. Black students wanted a vehicle which would give voice to Black concerns.

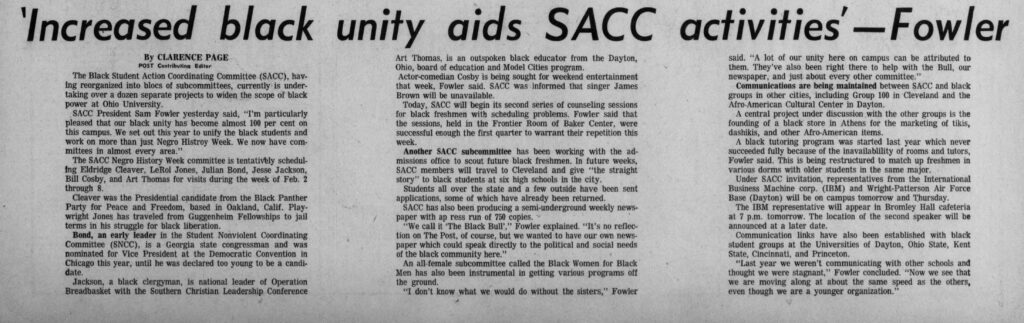

The Black Bull

The first documented attempt at a Black publication on Ohio University’s campus was The Black Bull, produced in 750 copies. The paper detailed feelings toward the university, national events, poems by both students and prominent Black activists, and songs, depicting experiences shared by the Black community. The Black Bull represented most importantly a space where Black students could speak freely for themselves instead of relying on The Post or the University President to speak for them. The publishing of The Black Bull allowed them to see that their experiences, no matter how they differed from the news as it was presented by The Post, were okay to talk and write about.

This is appropriately depicted on page 3 of The Black Bull when writer Larry Deering states,

“After talking with one of the soul sisters on campus, and taking a deep soul-searching look at myself, I finally came to realize that I was so much like many of my Black brothers and sisters on campus who believed that what is not written according to the status quo (that being the white man’s media) was lewd and atrocious.”

Deering continues by saying that,

“I wasn’t taking into consideration that what is said and how it is said in this paper typifies the way our Black masses speak.“

According to Deering, Black members of the community were primed to feel their depictions of reality were too harsh for the general public to read and digest (Dixon & Maddox, 2005) [OHIO login required]. The consumption of The Post and the voice of President Alden unintentionally had promoted the general perspective and attitude on OU’s campus that the Civil Rights activism was all going swell and that OU’s Black student population—indeed the Black population of the country—had no grievances. However, with The Black Bull, community members were able to see past the efforts of priming and speak to their true convictions.

The ability for Black students to do this was absolutely instrumental to having a true sense of a voice. While The Black Bull publication did not last, it laid the groundwork for future publications like The Afro-American Affairs, opening up a larger space for genuine experiences.

Putting it Together

President Vernon R. Alden’s leadership during the Civil Rights Movement served as a beacon of hope during a troubling time. His activism was absolutely crucial in shedding light on the racial injustice not just on campus but around the country. Furthermore, The Post reflected the power of Alden’s position, framing successes through his eyes. However, if we look at this time with a critical eye it is important to recognize that the voices unintentionally brushed aside in the process were those of OU’s Black student and community members. Despite the fact that it was the Black population who were living through these experiences, their stories were told through the lens of white institutions and voices.

When we listen to and amplify marginalized voices we can support the telling of authentic narratives. The true experiences had by Black members of society were ones of perseverance and strength. It is a narrative that deserves to be heard as they are the heroes of their stories. It is not those who attempt to do it for them, only doing them an ounce of justice. It is publications like The Black Bull, and, after that, The Afro-American Affairs newspaper that have displayed the true nature of the Black experience and have created a space where Black voices are not filtered. When we allow marginalized communities to freely express their own voices, we help pave the way for genuine expression and a more equitable future in media and beyond.

References

- Halpern, M. (2019). Feminist standpoint theory and science communication JCOM 18(04), C02. https://doi.org/10.22323/2.18040302

- Lance Bennett, W. (2016). Indexing theory. The International Encyclopedia of Political Communication, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118541555.wbiepc18

- LaPoe, B. & Broussard, J. (2018). History and an interpersonal community perspective. In LaPoe, V., Olson, C., & LaPoe, B. (Eds.), Underserved communities and digital discourse: Getting voices heard (pp. 137–156). Lexington Books.

- LaPoe, V., & Reynolds, A. (2013). From Breaking News to the Traditional News Cycle. Electronic News, 7(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/1931243113484311

- Whitten-Woodring, J. (2009). Watchdog or lapdog? media freedom, regime type, and government respect for human rights. International Studies Quarterly, 53(3), 595–625. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2478.2009.00548.x