By Darcie Zudell, Journalism: News and Information ‘26, Shyla Algeri, Journalism and Strategic Communications ‘26, Ally Parker, Visual Communications ‘26 and Gigi Twachtman Media Arts Production ‘27, for JOUR 4130 Gender, Race, and Class in Journalism and Mass Media with Victoria LaPoe, Spring 2025.

During the spring 2025 semester, the staff of the Mahn Center for Archives and Special Collections worked intensively with Victoria La Poe’s JOUR 4130 class, Gender, Race, and Class in Journalism and Mass Media. The students explored, selected, and researched materials from the collections, then worked in small groups to prepare presentations. The students had the option to then expand their research into a blog post like this one for their final project.

The Beginning of Free Speech Policies at Ohio University

President Vernon R. Alden was the first to lay groundwork for free speech policies at Ohio University. His “Speakers Policy”, released in 1962, unequivocally supported students’ freedom of expression. Students took that progressive policy in stride and organized protests on College Green and other parts of campus.

“Some people may fear that this posture could expose our students to dangerous manipulators and radical demagogues and that they would be persuaded to join causes disloyal to the United States. We disagree because we have deep faith that our students have the ability to challenge effectively unsound principles and deceptive ideologies.” – “Speakers Policy”, established in 1962 by Vernon R. Alden.

In 1966, OU decided its policies needed to be a bit more established, thus, introducing a “Demonstrations” section to the 1966-1967 student handbook. The changes featured restrictions on where students could assemble, what time protests could take place and on the materials handed out during rallies.

Although the protest policies were more developed, OU was not prepared for May 4, 1970, when the national guard shot and killed four students at Kent State University during a protest against the U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War.

Student Media Coverage of May 4, 1970 and Vietnam War Protests

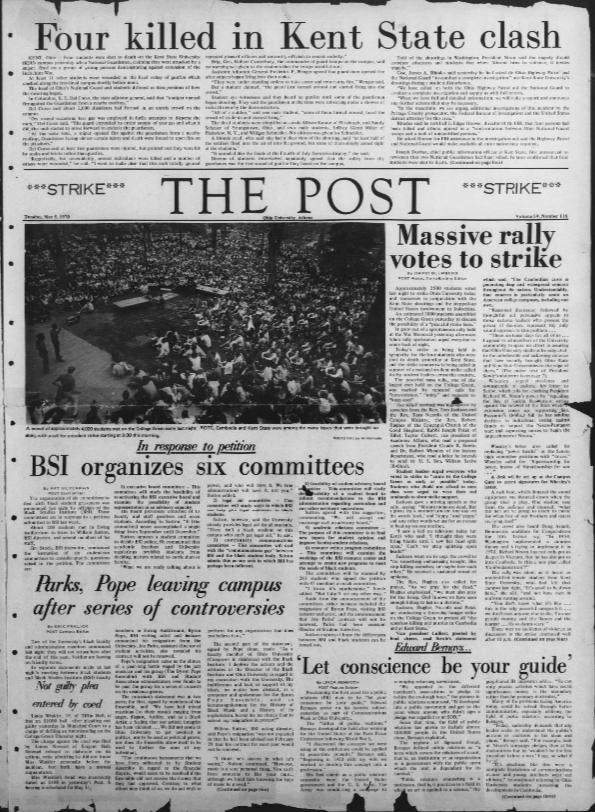

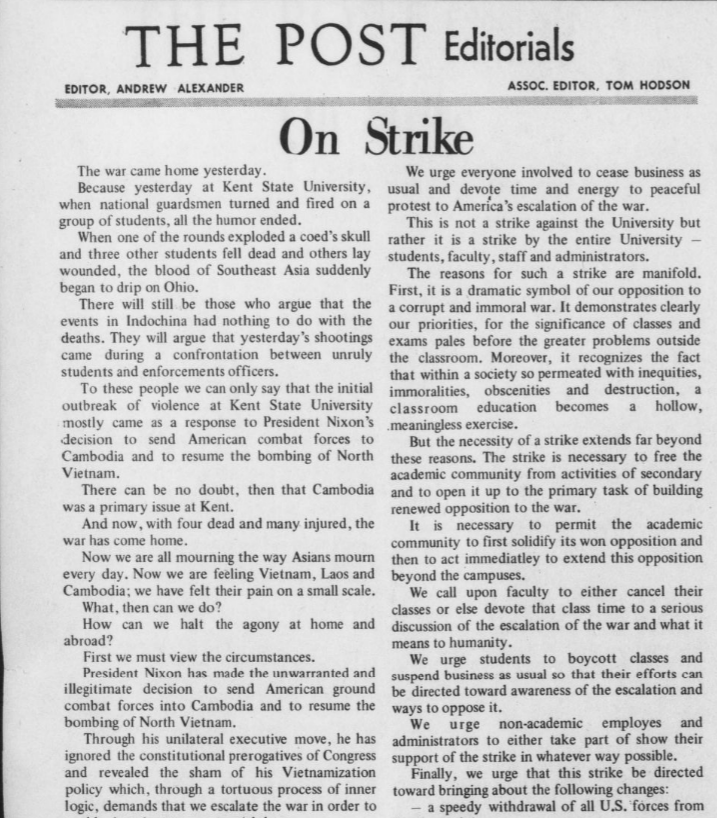

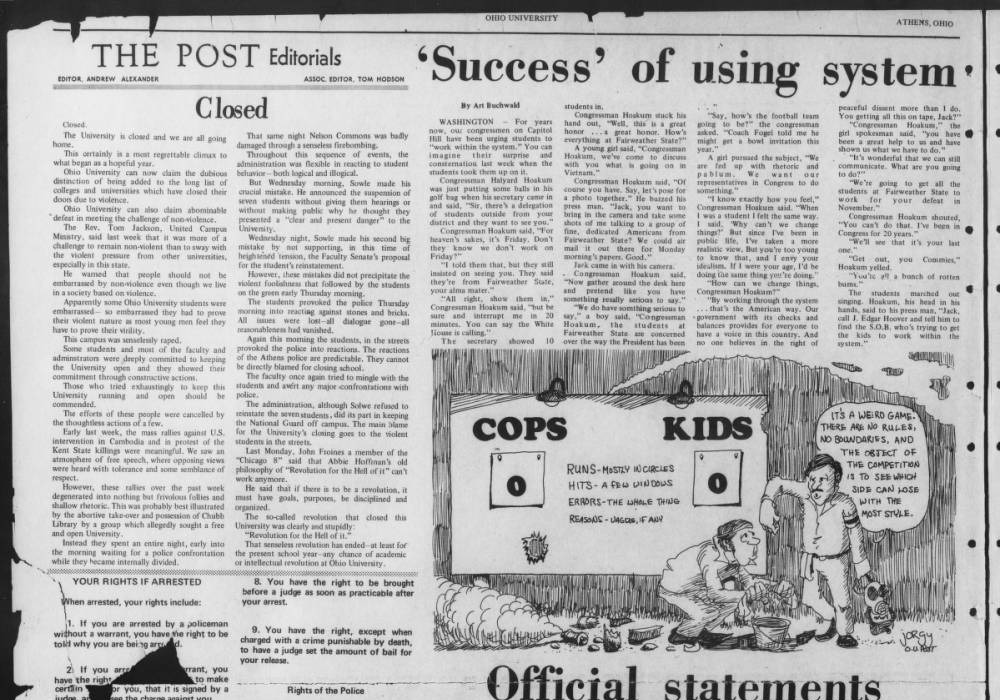

The Post covered the Kent State Shooting protests, up until the shutdown on May 15. Andy Alexander, the editor-in-chief of The Post from 1969 to 1970, also showcased writing and reporting on student protests. He published many editorials endorsing a university strike in response to the Kent State shooting. When protests became violent and a school closure loomed over OU, The Post promoted peaceful protest without continued destruction and violence.

“We want to make our opposition known, but we are frustrated because no one seems to hear us. We can protest peaceably, yet it is those who protest violently who receive the media’s headline” – “What’s Next” editorial, published in The Post on May 7, 1970

From May 5 to May 15, almost all of the cover stories (and most of the stories in general) were about student protests and keeping the university open. This issue was of high importance to college students because it was directly affecting them.

The Post published several cartoons that would resonate deeply with students. Photos of the National Guard on campus were jarring and likely provoked a reaction from parents, students and faculty.

Though the theory of media encoding typically pertains to TV and online journalism, the Athena used encoding in their layout for the 1970 yearbook. Though not outright condemning the organization, they used imagery and text that criticized the ROTC. The students’ writing regarding protests were incredibly personal and reflected the student attitude of the war.

“The first two wars were ‘GOOD’ wars — a seeming contradiction in terms, but Patriotism overrules morality PRO PATRIA MORI. We were right, we won… ROTC enrollment grew by leaps without boundaries.” – Writing alongside photos of the ROTC students in the Athena yearbook, published in 1970.

House Bill 1219 and Free Speech Zones

The riots in 1970 led to swift legislative action. Ohio House Bill 1219, enacted in 1970 and commonly known as the Ohio Campus Disruption Act, passed directly in response to the protests against the Vietnam War, which grew more violent following the Kent State shootings.

The bill took away students’ rights to due process, insisting that any student or faculty member arrested at mass demonstration would face immediate suspension, without an investigation; of course, students and faculty could make appeals.

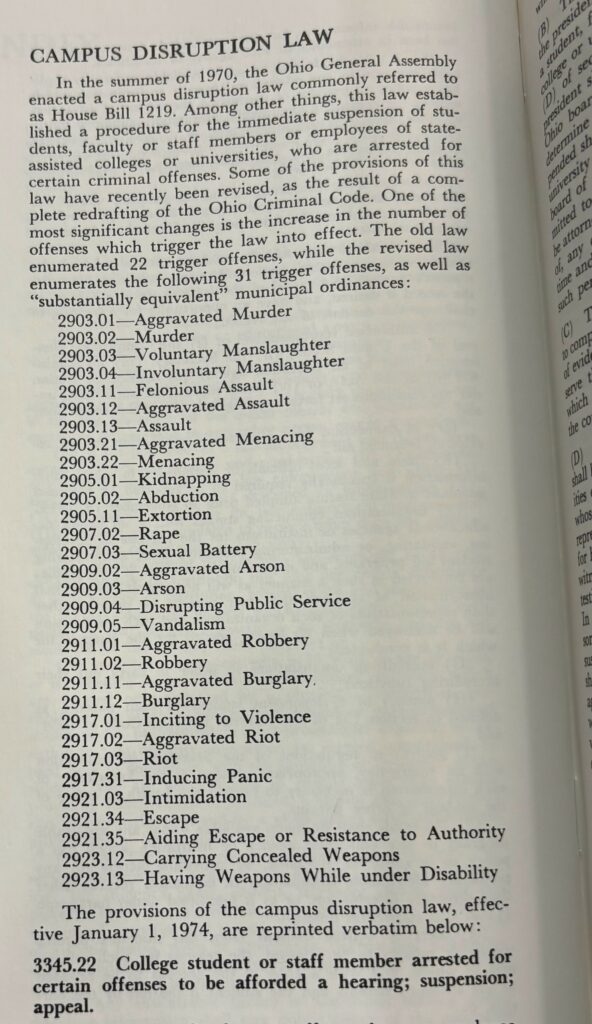

In 1974, the student handbook acknowledged provisions made to the law. Under its “CAMPUS DISRUPTION LAW”, nine additional trigger offenses were acknowledged. Additionally, the 1974 amendment extended law offenses to the “immediate vicinity” of the university.

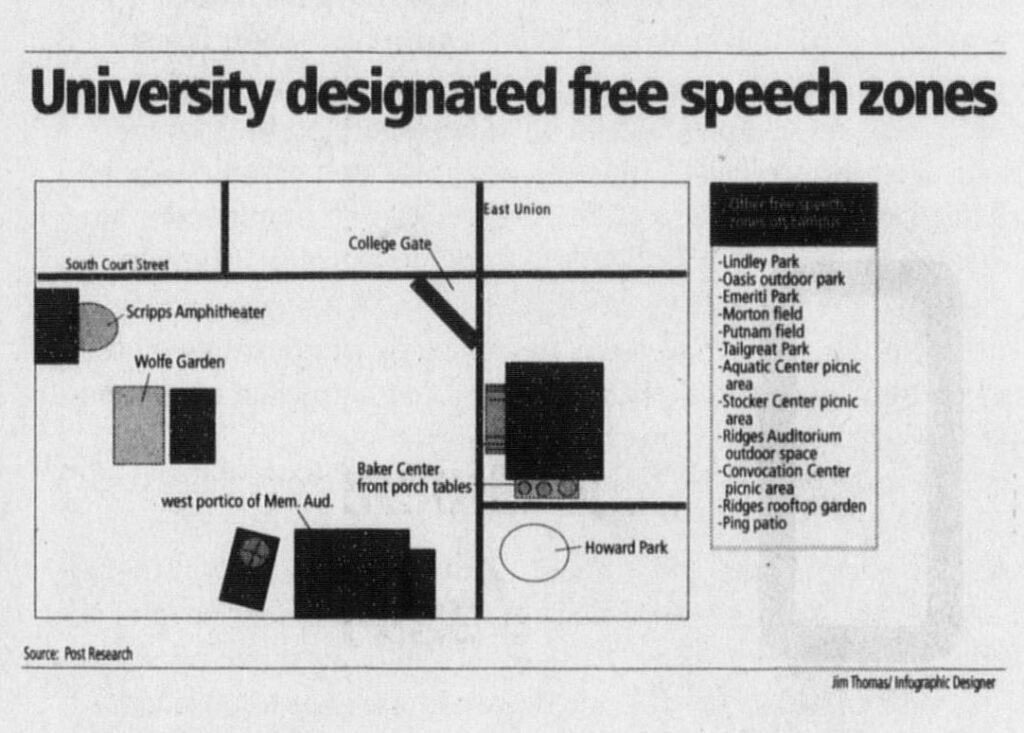

In 2003, OU followed the trend of many other universities by establishing “free speech zones.” There were 19 established zones, each one with restrictions on sound amplifiers and time of protest. Protests outside of these zones weren’t necessarily banned but rather heavily restricted. Students who do not reserve an area in advance are subject to university intervention, whether that be forcing demonstrations to move locations or disband entirely.

“But the purpose of a protest or demonstration is not to be docile or unobstructive. Protests aim to draw attention to a cause, raise awareness and gain support. This cannot be achieved by gathering quietly at an out-of-the-way site.” – “Campus should abolish free speech zones” published in The Post on Oct. 14, 2003.

University Protest Policies in 2025

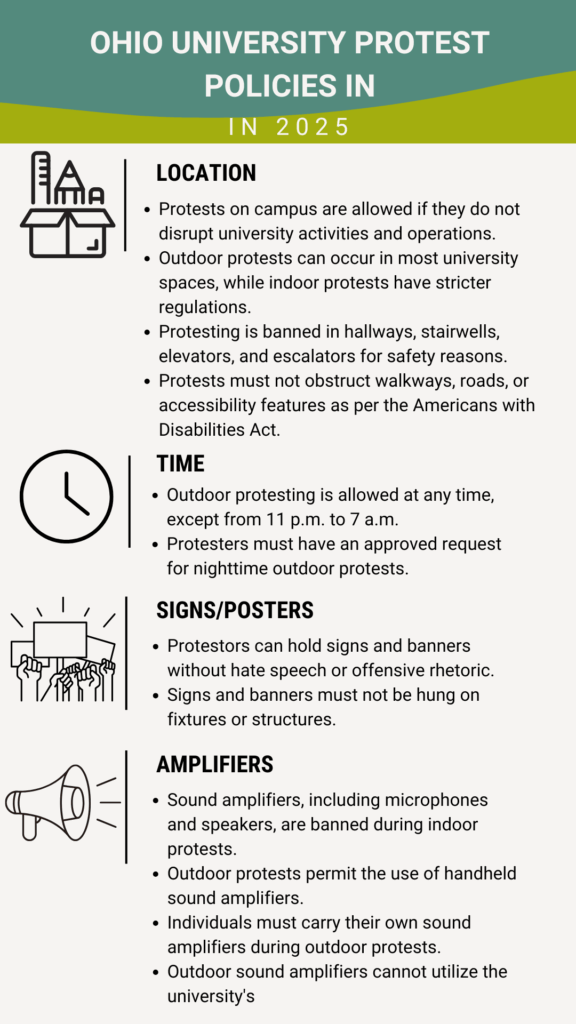

Protests are permitted on campus so long as they do not substantially disrupt university activities and operations. Disruption largely depends on context; however it is stated that mere inconvenience is not grounds to forcefully end a protest. Policies for protests vary depending on the location, time and manner of expression.

Individuals who violate these policies may be asked to leave the area, face institutional discipline if students or faculty, or be arrested if the violation constitutes a crime.

Freedom of expression is currently at risk, especially regarding universities and protesting rights. The current administration stated that colleges and universities that allow “illegal protests,” which is loosely defined, will lose all federal funding.

Recent Protests at Ohio University

The Black Lives Matter protests set up crucial groundwork for future social movements by amplifying the role of digital activism and social media in mobilizing large-scale, decentralized protests. It demonstrated how online platforms had the power to unite people around shared causes, breaking down geographic and social barriers. BLM also showed the importance of intersectionality, connecting racial justice to broader issues like LGBTQ+ rights, gender equality, economic justice, and immigrant rights. The Black Lives Matter Movement has shaped future protests by recognizing and addressing multiple forms of oppression simultaneously. Additionally, BLM helped redefine what effective activism looks like in the 21st century, focusing on non-violent protest, direct action, and holding institutions accountable for systemic injustice.

Recent protests at OU demonstrate how protest rules and regulations have become more specific in terms of restrictions over time. One example of this is the “Baker 70” protest from 2017. This was a peaceful sit-in protest, where students and community members met in Baker University Center in response to President Donald Trump’s travel ban. At this protest, 70 people were arrested for allegedly creating a safety hazard and causing disruption. Since the Kent State shooting protests, OU has limited indoor protests to certain locations, such as Baker Center. According to Ohio University’s policies, that location offers an environment to safely assemble. Protesters must follow occupancy limits and building code guidelines, which can be difficult to manage.

Another example of a more structured protest was a march organized by the Students for Justice in Palestine urging Ohio University to divest from Israel in 2024. Outdoor protests have less regulations and can generally happen anywhere on campus, as long as they don’t disrupt university operations. This particular protest offered more structure, with organizers discussing precautions online. On Instagram, the Athens Justice Coalition recommended protestors wear face coverings to protect their identity and turn off their phones to help prevent surveillance by police. Although protestors can voice their opinions and advocate for divestment, Section 9.76 in the Ohio Revised Code prohibits any public university in Ohio from divesting from Israel.

While The Post and The Athens News still report on student movements, much of the protest organization now happens through social media. Students continue to hold power in their voices, but the mediums and strategies have evolved.

References

Layton, M. (2025, April 14). Protesters ask Ohio University to divest from Israel. The Athens News. https://www.athensnews.com/news/campus/protesters-ask-ohio-university-to-divest-from-israel/article_5624dde2-0c5e-11ef-adfb-17da86bcce61.html.

Morris, C. (2017, February 1). More than 70 protesters arrested after sit-in at Baker Center. The Athens News. https://www.athensnews.com/news/campus/more-than-70-protesters-arrested-after-sit-in-at-baker-center/article_be075b34-e8d4-11e6-97bd-37b4d959c9af.html.

Ohio Rev. Code § 9.76. (2022, July 21). Boycott provisions in certain contracts. Ohio Laws. https://codes.ohio.gov/ohio-revised-code/section-9.76.

Ohio University. (2024, September 26). 01.042: Use of indoor spaces. https://www.ohio.edu/policy/01-042.

Ohio University. (2024, September 26). 01.044: Use of outdoor spaces. https://www.ohio.edu/policy/01-044.https://www.ohio.edu/policy/01-044

Ohio University. (2024). Freedom of Expression FAQ. https://www.ohio.edu/student-affairs/expression/faq.

Ray, R. (2022, October 12). Black Lives Matter at 10 years: 8 ways the movement has been highly effective. The Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/black-lives-matter-at-10-years-what-impact-has-it-had-on-policing/.

Rose, A. (2025, March 13). Can protesting in the US be ‘illegal’? Trump’s vague warning raises constitutional questions. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2025/03/13/us/protests-legal-illegal-constitution-trump/index.htmlhttps://www.cnn.com/2025/03/13/us/protests-legal-illegal-constitution-trump/index.html.

Ohio University. (2018, July 26). 01.040: Statement of commitment to free expression. https://www.ohio.edu/policy/01-040.

Ohio University. (n.d.). History of free speech and activism at OHIO. https://www.ohio.edu/student-affairs/expression/history.

Lewis, J. M., & Hensley, T. R. (n.d.). The May 4 shootings at Kent State University: The search for historical accuracy. Kent State University. https://www.kent.edu/may-4-historical-accuracy.

Ohio Administrative Code. (2016, November 13). Rule 3339-3-20: Disruptive behavior and the 1219 procedure. https://codes.ohio.gov/ohio-administrative-code/rule-3339-3-20.