By Adrian Darden Kautz, History ’27, Digital Initiatives Assistant

Working in Digital Initiatives at Alden Library has opened to me many wonderful opportunities to digitize and research unique collections from the Mahn Center for Archives and Special Collections. A recent opportunity I had to photograph two Ohio University herbaria from the rare book collection sparked in me an interest for these unique plant portfolios. As I worked with the collections of plant specimens carefully placed into books, some questions came to mind. What really is a “herbarium”? Who made herbaria, and why? What do these objects tell us about the time in which they were made and about the people who made them? The questions I had pushed me to research the subject of herbaria, botany, and women in science.

First things first, what is an herbarium? The definition that Merriam-Webster gives is “a collection of dried plant specimens,” usually arranged in an orderly fashion. Simple enough, it seems. What Merriam-Webster fails to distinguish is the why of it all. Why do people make herbaria? One clear answer is for the science of botany and plant research. Well known biological scientists such as Carolus, or Carl, Linnaeus and Charles Darwin created herbaria with countless specimens from all over the globe to aid in scientific research and discovery. While the names and contributions of these men are common knowledge, I would dare to say that most people don’t know the names Almira Phelps, Ynes Mexia, or Alice Eastwood. These women, along with many others, made significant contributions with their research in the science of botany. Even Emily Dickinson, famed poet, had her hand in plants and the creation of herbaria. (See a facsimile, or exact copy, of her herbarium here). Despite the importance of their work, female botanists, both professional and hobbyist, have long been overlooked. But when, why, and how did women indulge in this field?

Botany has been an important segment of science for a very long time, however, women were not commonly involved until the 18th and 19th centuries. Charles Darwin published his On the Origins of Species in 1859, which pushed a fascination with natural history to the Victorian public eye. Women especially were interested in collecting and preserving specimens of plants, animals, and insects. Plants were the most accessible and acceptable for women to study. A woman’s connection to plants went beyond what was in her garden, to connecting ideas of fragility and femininity. Additionally, it was in the 18th century that the education of women in science became more present. Education, especially of the youth, was the easiest way for women to get involved in botany and scientific study.

Education was not an equalizer for men and women. The notion that women were less-than men was not reversed with the boom of scientific education for women in the 18th and 19th centuries. While educators like Almira Phelps contributed to making science a “standard course of study” for all youth, there were still strong misogynistic ideas about women and their education (Baym). Phelps herself, hailed as “one of the science’s intellectual leaders in the United States,” also believed that women should be educated, especially in botany, but it was because women were unruly and undisciplined (Baym). Almira Phelps was most often referred to as “Mrs. Lincoln Phelps,” when she authored works, some of which can be found here. Phelps and other scientists hoped that the structure of science and Linnaean taxonomy for plant identification would “redeem the whole sex,” (Baym). Beyond the idea that education could fix women, botanical education could also give women a role outside of wife and mother. While many women went further in their scientific endeavors, the most acceptable form of botany for women was simply to educate their children. The idea that mothers should teach their children, but not botanize outside the home was strong enough that in the late 18th century, “a set of practical instructions for how women, especially mothers, might teach botany to children” was created (Baym). This work and other societal standards, however, kept women away from more detailed scientific endeavors.

As I began to read and understand the history of women in botany, nuance in the phrase “botanizing women” was significant. Women have been compared to flora for a very long time; beauty, fragility, and defenselessness were considered common traits of women and plants through the centuries. The term “botanizing women” originally meant the “personifi[cation of] women as flowering plants,” which was often depicted in art (Kelley). Over time, as women became more educated and involved in science, the term shifted meaning from women as flowers to women who studied flowers. The idea of feminine fragility, however, was persistent even without the comparison. The Linnaean taxonomy that was a driver in botanical research was seen by some as too harsh for women to study. There are two sides to every coin, and that was true with women and the study of botany. While botany was “often considered one scientific pursuit suitable for women,” the structure of study that Linnaeus had presented was “rather shocking for a female audience,” because Linnaeaus, “chose sexuality as the key,”(Kelley). It was difficult to bridge the gap between reasonings. Studying animals was clearly unsuitable for women because of the importance of mating habits. Plant biology, however, could also “invite…thinking about sex” due to stamens and pistils, the sexual organs of plants, being a prominent area of study in the Linnaean system (Kelley).

How then did women become so involved in botany? Women could be educated in botany as children, and it was permissible for adult women to teach young people. Women had a deep connection to plants and flowers because of their societal similarities, both being perceived as fragile yet beautiful. Despite the education and connection that women had to botany, their scientific achievements were often disregarded. It was common, therefore, for women to downplay their knowledge in order to remain acceptable. Women would delegate to experts in order to “distract…attention from the fact that their own botanical knowledge went well beyond an acceptable minimum,” (Kelley). Others focused on the artistic and aesthetic importance of plant life. To sketch or paint plants with watercolors was a way for “polite women… [to] do botany,” (Kohlstedt, Koerner). In spite of all the barriers, women in the 19th century, “engaged in all areas of botanical production,” from dissection and analysis, education, and “above all botanical drawings and engravings,” (Kelley). This sector of botany, artistic expression, is one key factor in why many herbaria are known to be authored by women. While it was not as common for women to write scientific texts about plants, their scrapbook-like herbaria were incredibly important to recording and categorizing plants.

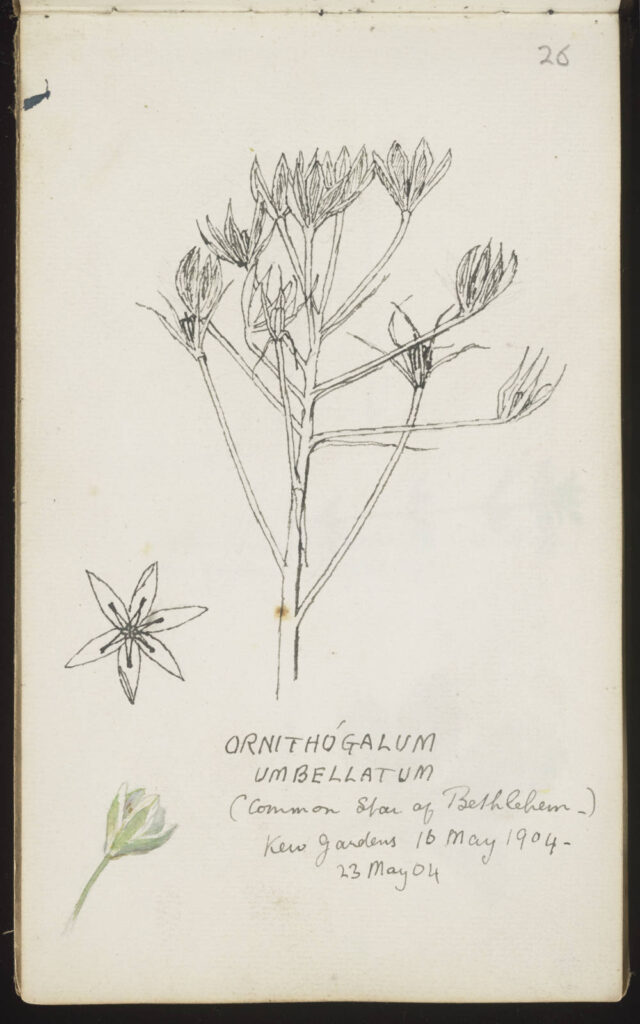

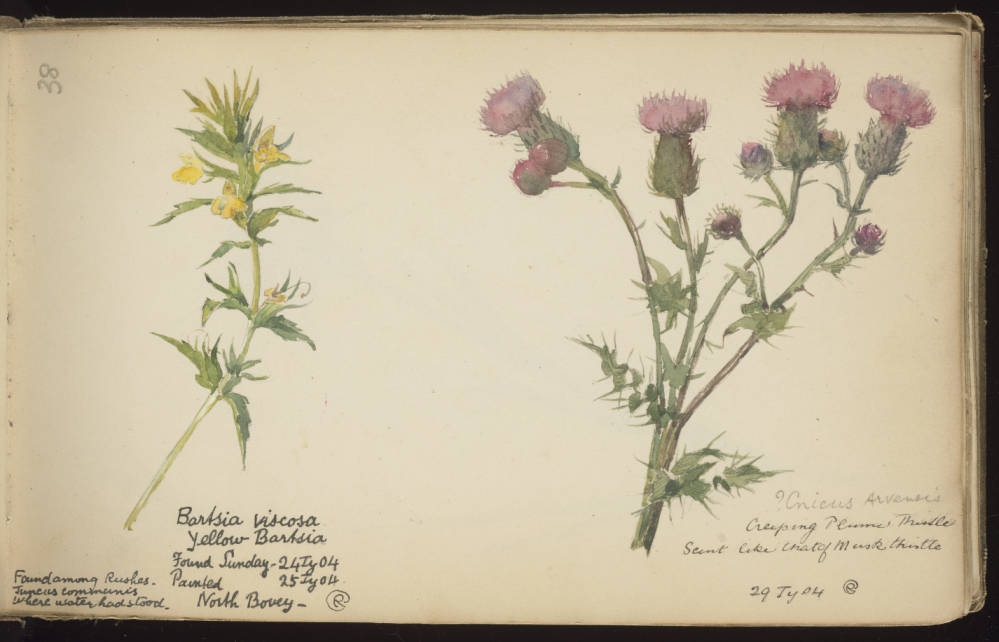

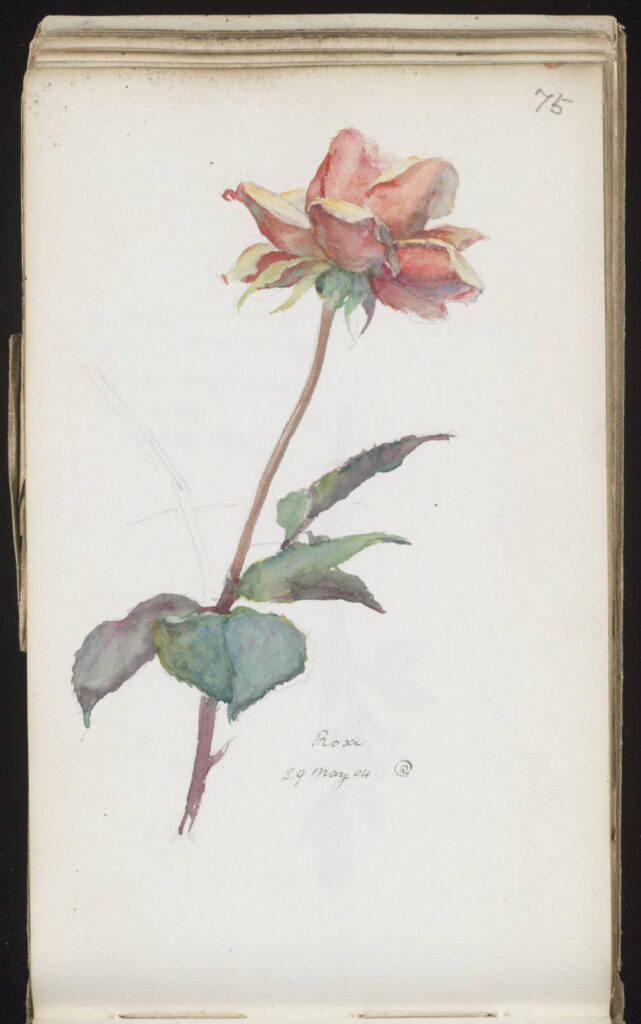

Herbaria were meant to catalog the world of plants. Women did much work in that regard, and they should be recognized for it. Ohio University owns multiple herbaria of pressed plants, at least three of which were created by women. While pressed plants are the most accurate version of a “herbarium,” drawings and other depictions can just as well detail what a plant specimen looks like and contains. A botanical sketchbook held by Ohio University and created by Clara Reynolds is one example of how the artistic-scientific thread can be made. The sketchbook, “A Flower-Lover’s Holiday”, is full of watercolor paintings that depict plant specimens of many kinds. Most of these specimen paintings are labelled with the species, location, and date when the subject was found. Including those pieces of information makes the sketchbook an important scientific work as well as an artistic work.

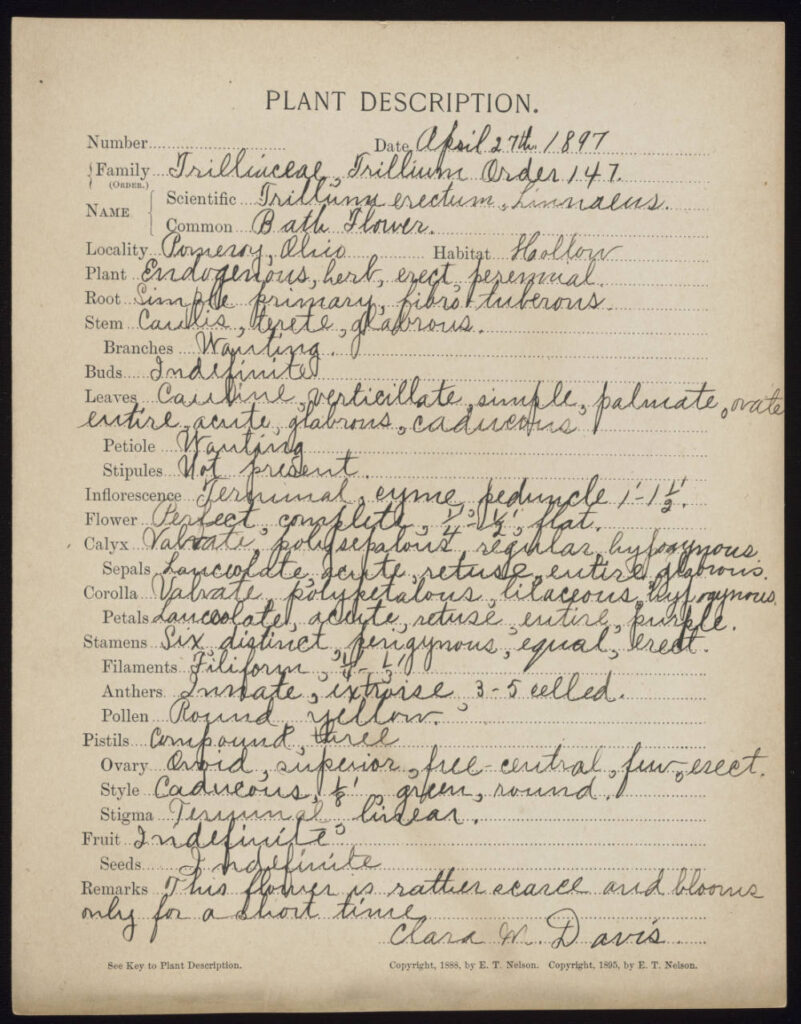

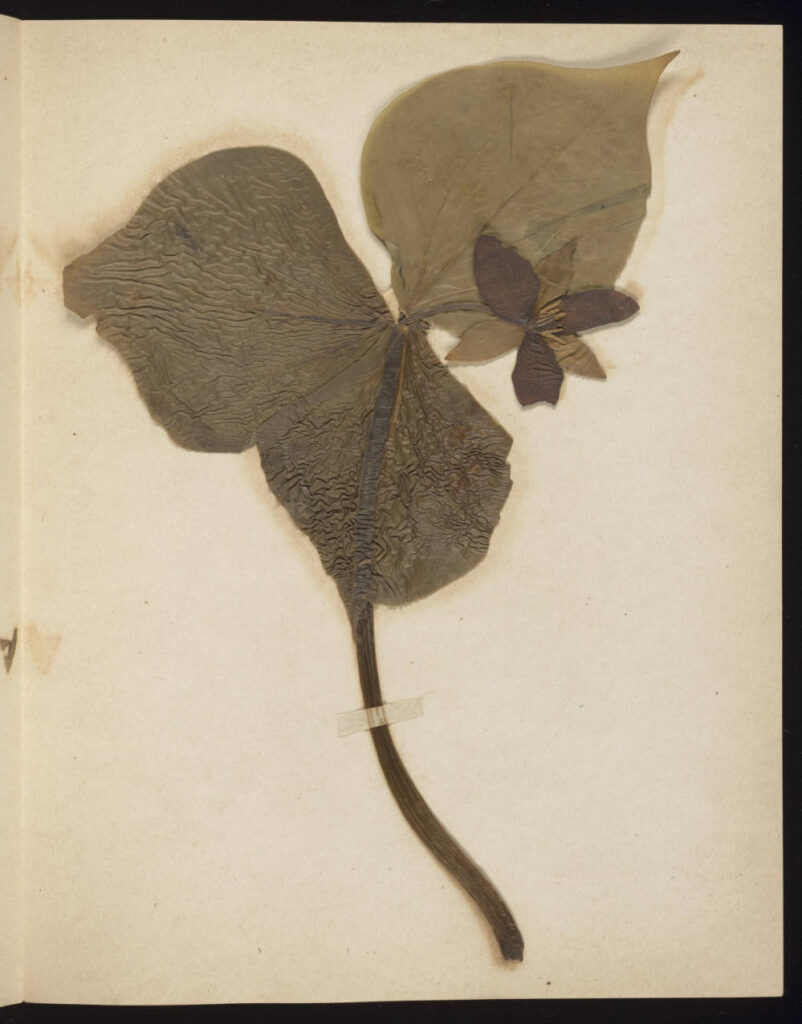

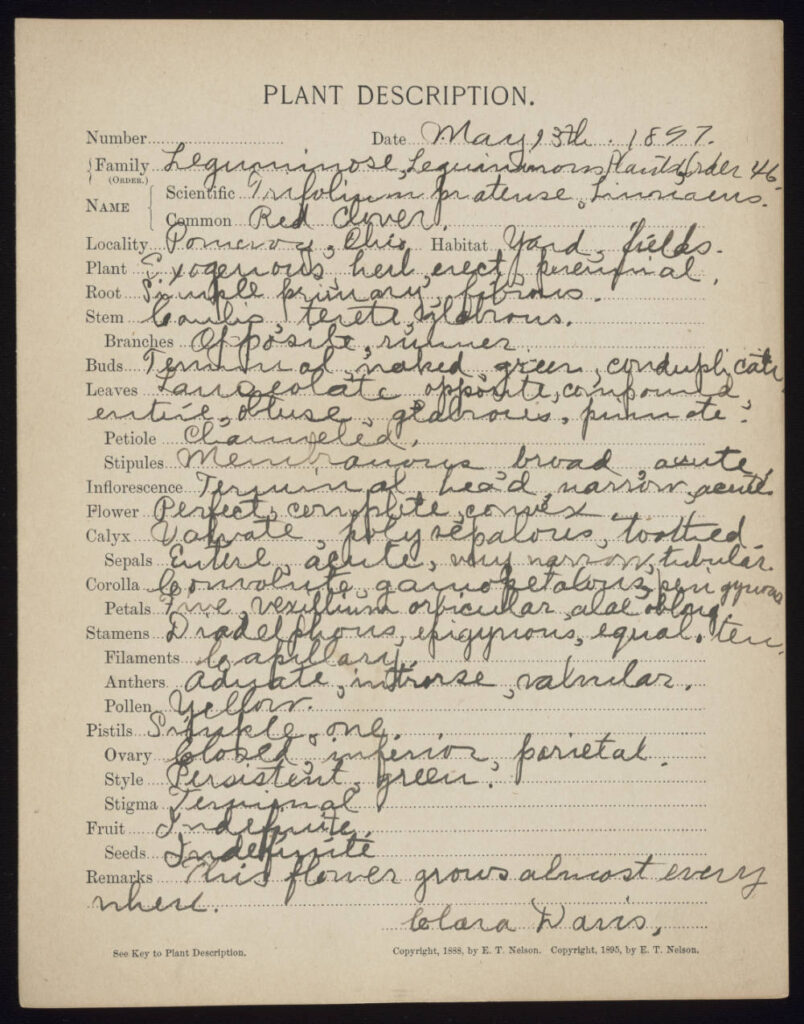

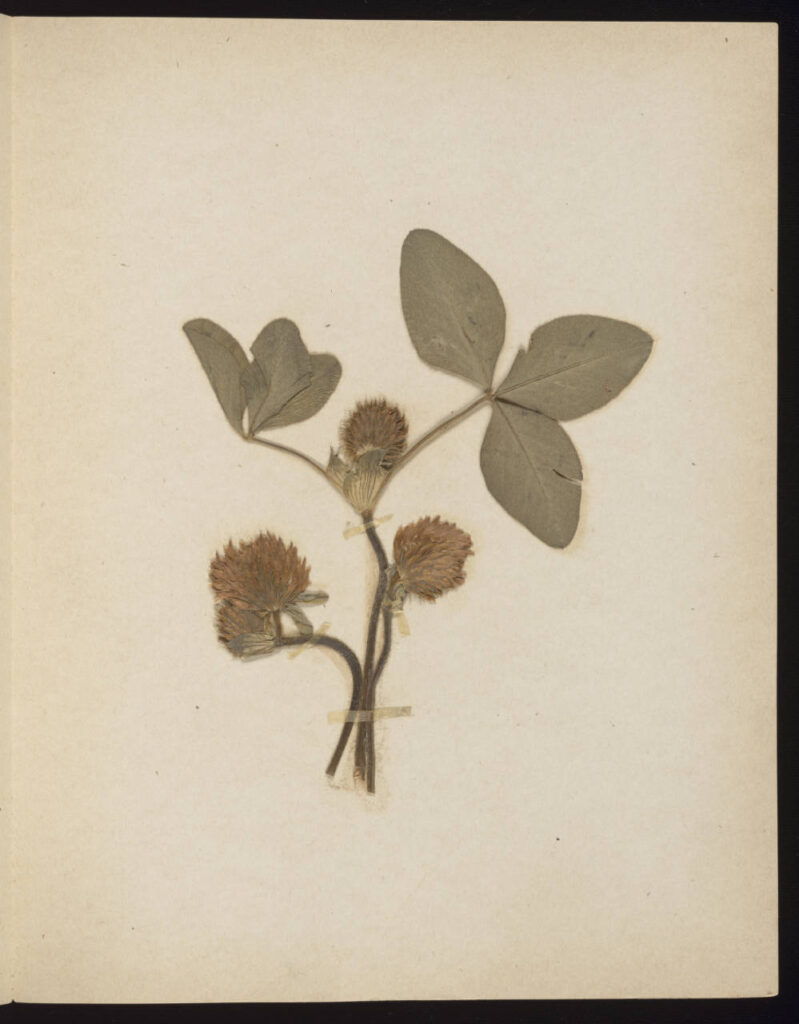

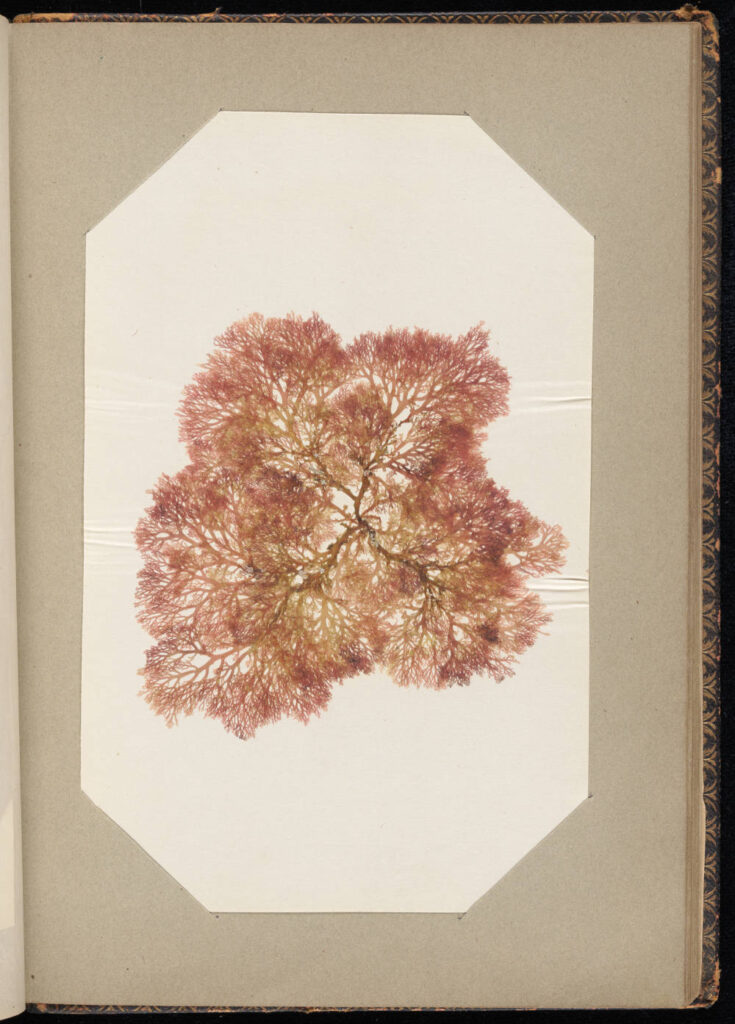

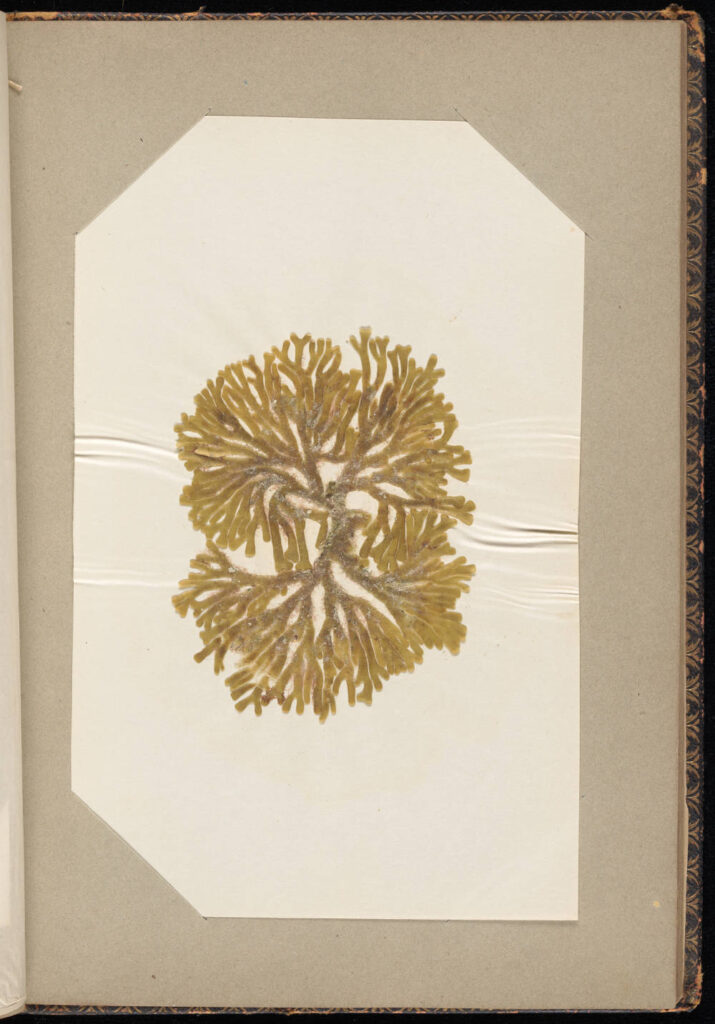

On the other hand, some women pursued botany more as a hobby, like Mary Eustis and Eliza Coleman did in their “Flowers of the Deep” herbarium of marine algae. The pressed algae are beautiful, but lack associated scientific or common names which could be used for study. Other OU herbaria, like that of Clara Davis, were created for educational purposes in specially created books entitled “Herbarium and Plant Descriptions.” While these works are not famed, they are wonderful examples of how women were able to indulge in scientific pursuits. That these pressed and painted plants have survived over a hundred years shows the care and time that these women put into their herbaria.

Women have been deeply involved in botany since the 18th century through education and creation. While there were many barriers to women entering scientific fields, there were also some opportunities. Despite the misogyny, women were able to become educated and educate others. Despite the botanization of women as weak flowers, they were able to reverse the meaning into women who botanized flowers. The incredible resilience and ingenuity that women in the 18th and 19th centuries possessed helped them to cement their place in botany. Although important female botanists are still overlooked, their work has persisted throughout time. The fact that Ohio University possesses multiple herbaria that were created by women attests to this. Whether as an artist, plant collector, or scientific researcher and educator, women were able to make their marks in the field of botany in the 18th and 19th centuries. Those marks are still important today as we continue to understand the world around us. Especially as plant species disappear from our world, we can look back to these incredible women I have mentioned, and their countless peers, for evidence of continued plant diversity and beauty in our changing world.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Baym, Nina. American Women of Letters and the Nineteenth-Century Sciences : Styles of Affiliation. New Brunswick, N.J., Rutgers University Press, 2002. Chapter 2: “Almira Phelps and the Discipline of Botany.”

Kelley, Theresa M. Clandestine Marriage : Botany and Romantic Culture. Baltimore, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012. Chapter 4: “Botanizing Women.”

Kohlstedt, Sally Gregory. History of Women in the Sciences. University of Chicago Press, 1999. Koerner, Lisbet. “Goethe’s Botany: Lessons of a Feminine Science.”

Reiss, Malia N. “Badass Babes of Botany.” UC Davis, 13 June 2023, www.ucdavis.edu/climate/news/badass-babes-botany.

“The Victorian Female Passion for Botany.” Gypsyscarlett’s Weblog, 29 Dec. 2009, gypsyscarlett.wordpress.com/2009/12/29/the-victorian-female-passion-for-botany/.