By Alex Rienerth, ’25, MA in Literary History, 2024-2025 Graduate Assistant in Rare Books

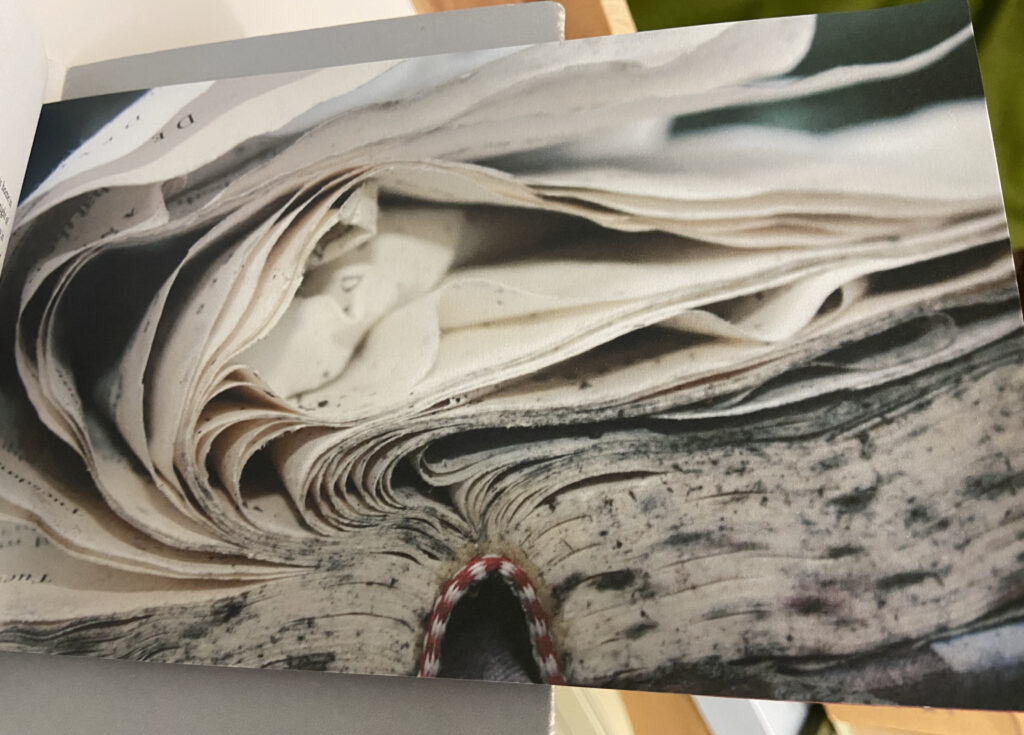

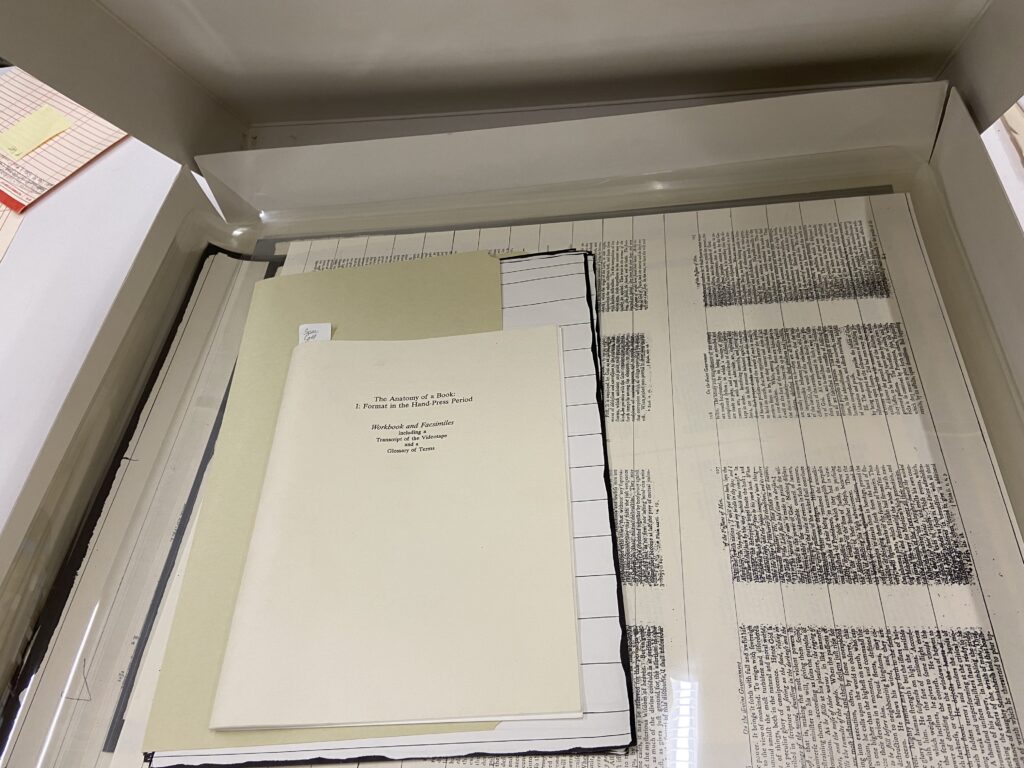

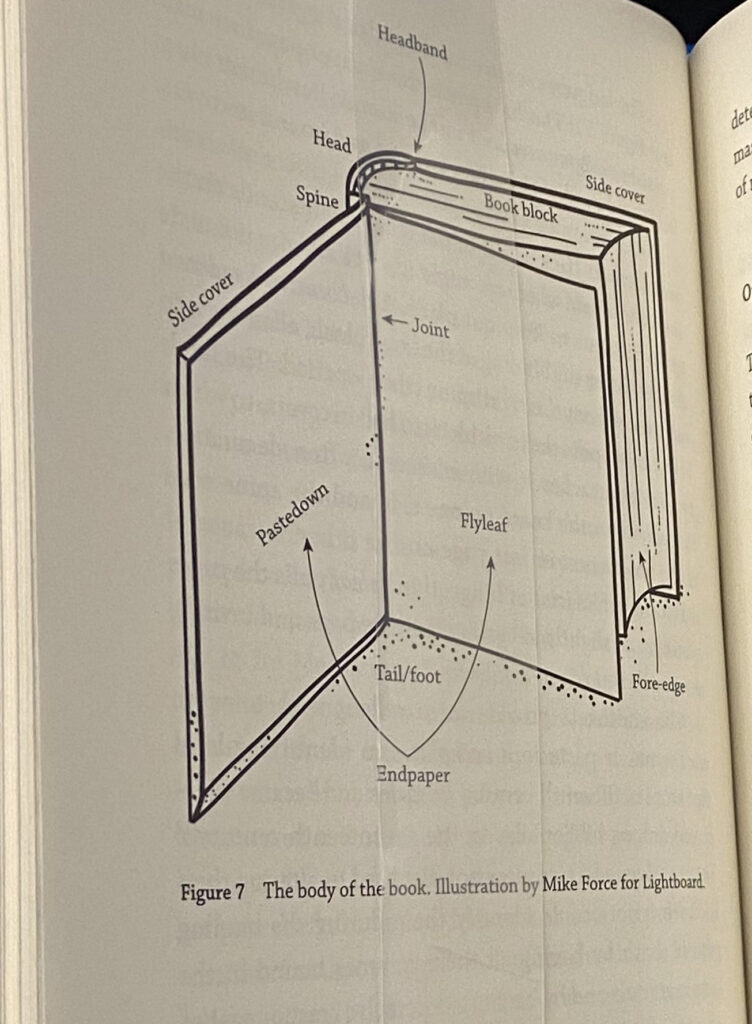

At the beginning of my graduate assistantship in the rare books department, part of my training included watching “The Anatomy of a Book,” a wonderful instructional video captured from an early 1990s VHS tape. Though the video is a bit peculiar, it was helpful for gaining a baseline understanding of how older books were produced and the terminology used to describe them. In addition to its contents, the title of the video caught my attention; I started to consider the kinds of anthropomorphic language we use to describe books.

While I made my way through the other training materials, I learned that other names of body parts are similarly applied to books: I’d been familiar with the book’s “spine” beforehand, but I wasn’t aware that they also had “heads” and “joints.”

So, when I was asked to curate an exhibit, I knew I wanted to try to do something meaningful with the interplay between books and bodies. Vague as this idea was, I started with an ALICE catalog search on our library website; I searched broad keywords like “anatomy,” “bibliography,” and “medical” and made sure to specify under the “location” that I was looking for items in Archives & Special Collections. I kept a running document of ALICE links of records that seemed relevant and interesting, then extended my search to holdings catalogued under the same subject and with similar call numbers.

Once I was done searching online, I had a long list of books I could potentially include in the exhibit. I was working with a smaller display case, though, so I needed to narrow things down a lot.

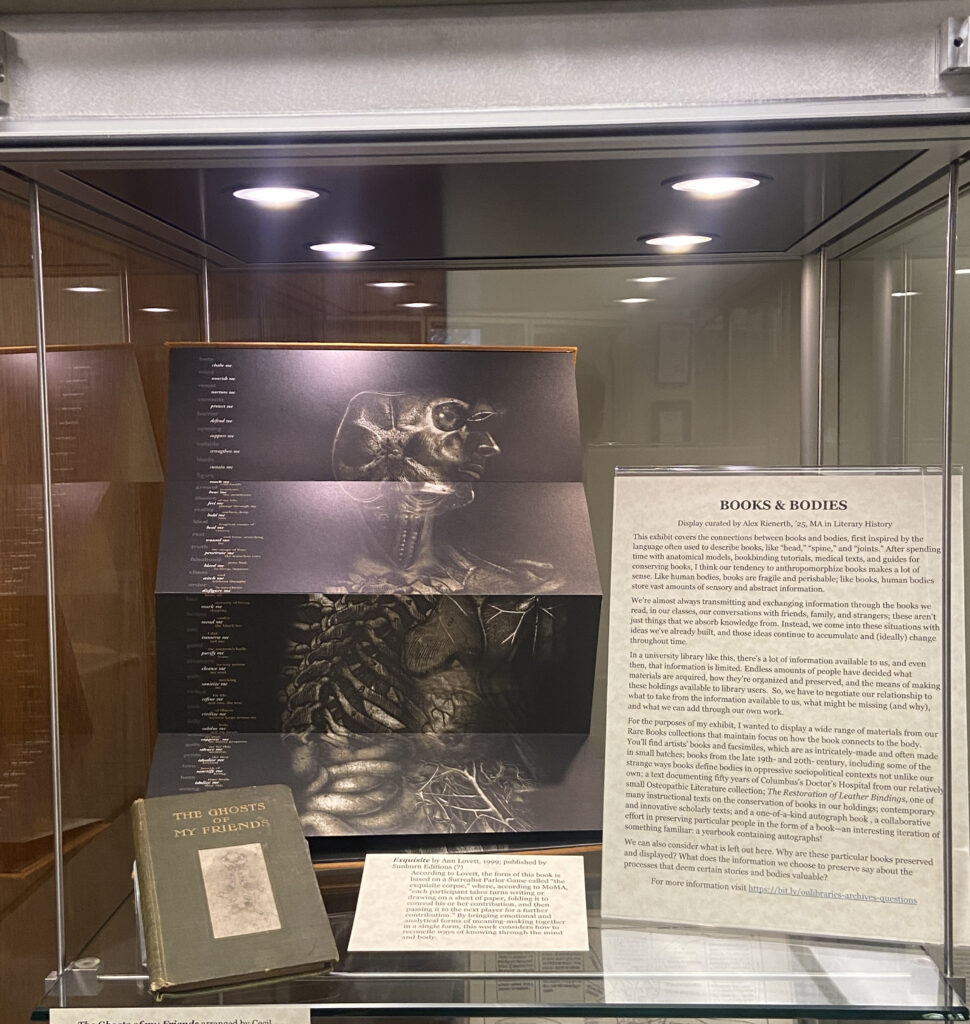

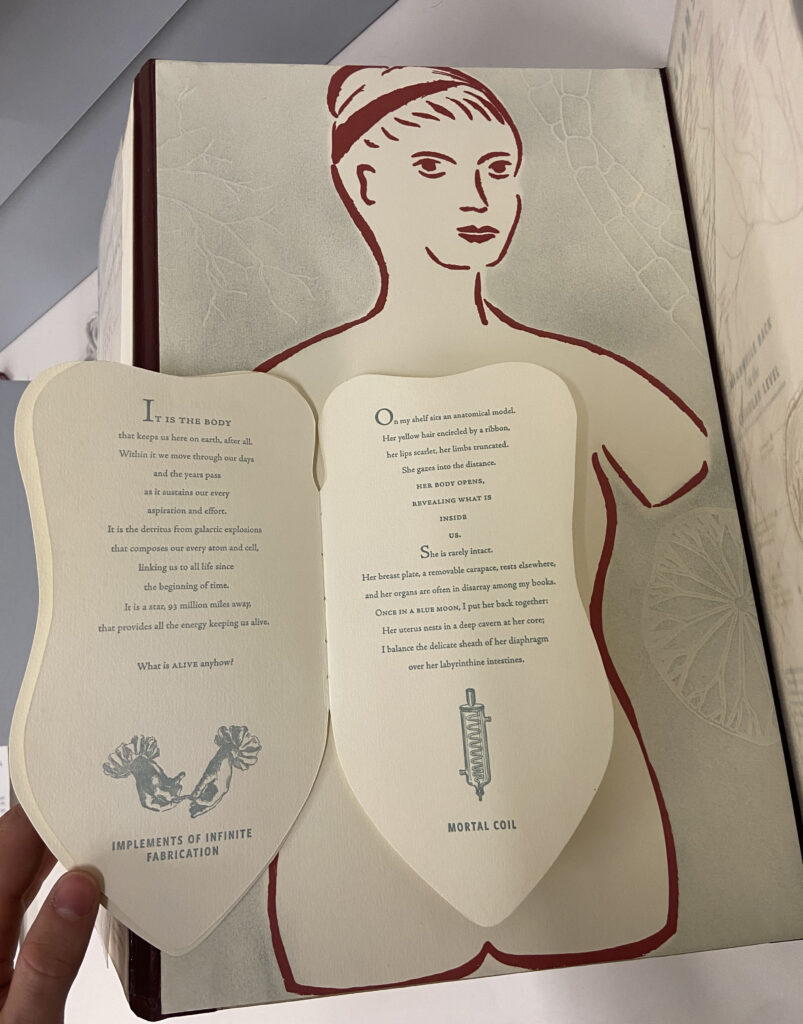

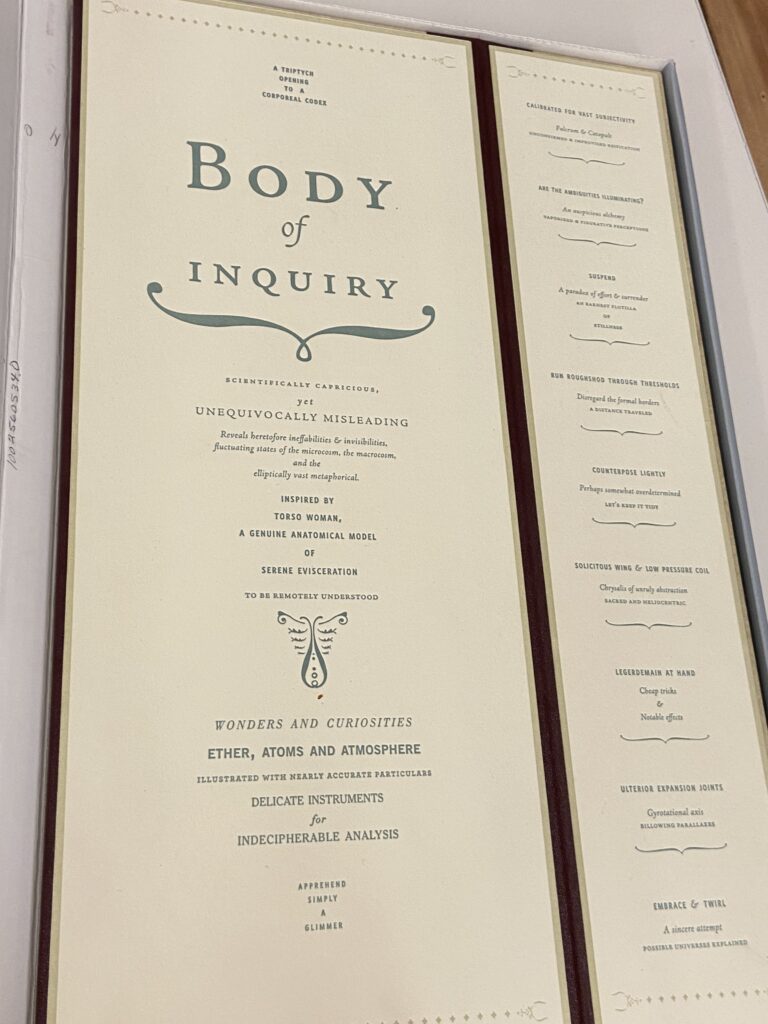

Details of Ann Lovett’s Exquisite (left) and Casey Gardner’s Body of Inquiry (right); I originally found Exquisite, which is included in the exhibit, while looking for books similar to Gardner’s.

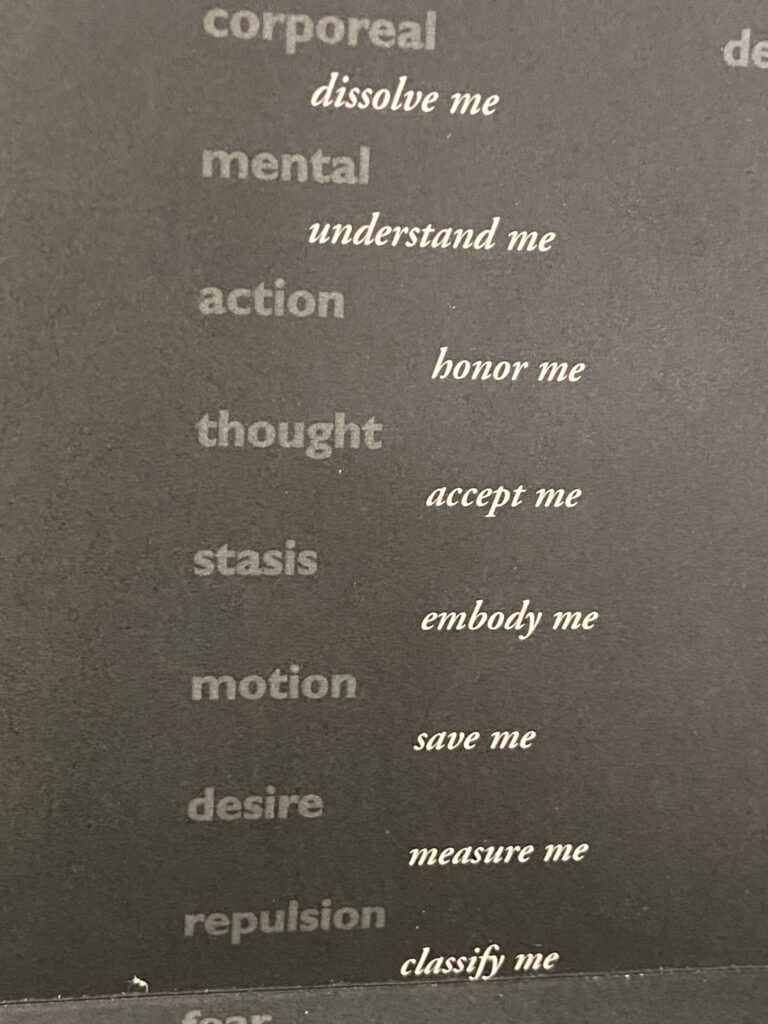

From here, my original broad topic had split into two potential directions for the exhibit: I had books that illustrated a relationship between the written text and embodiment while others highlighted the physical connections between books and bodies. In retrospect, I probably ran into this problem because I’d been thinking of books in terms of the words on the page for so long that it was difficult to shift my focus toward their more tangible aspects.

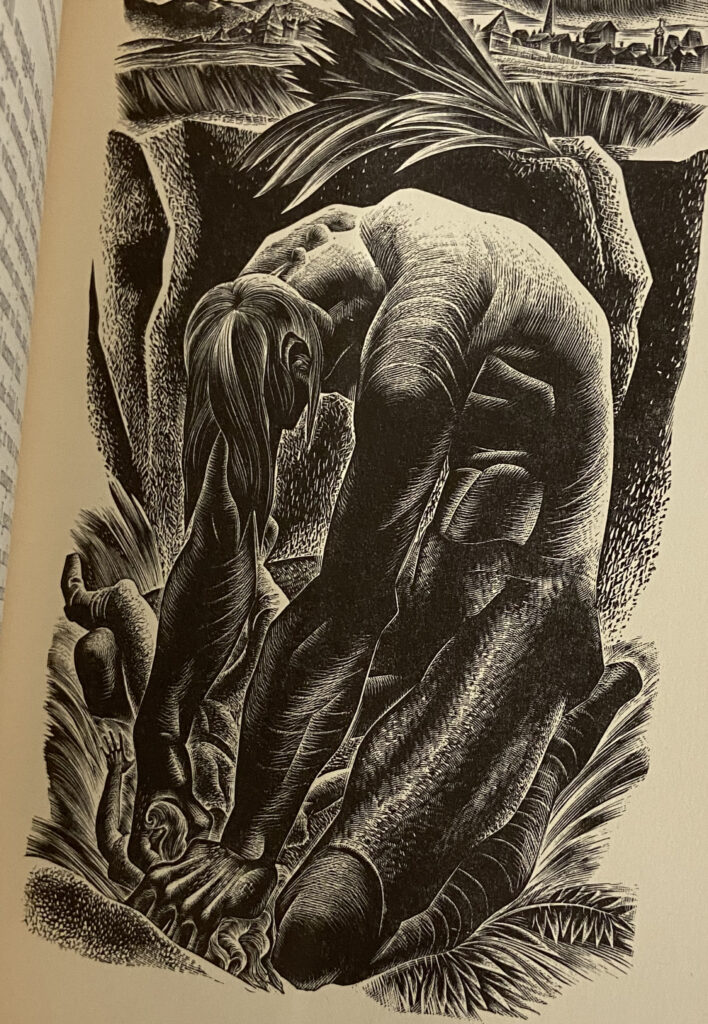

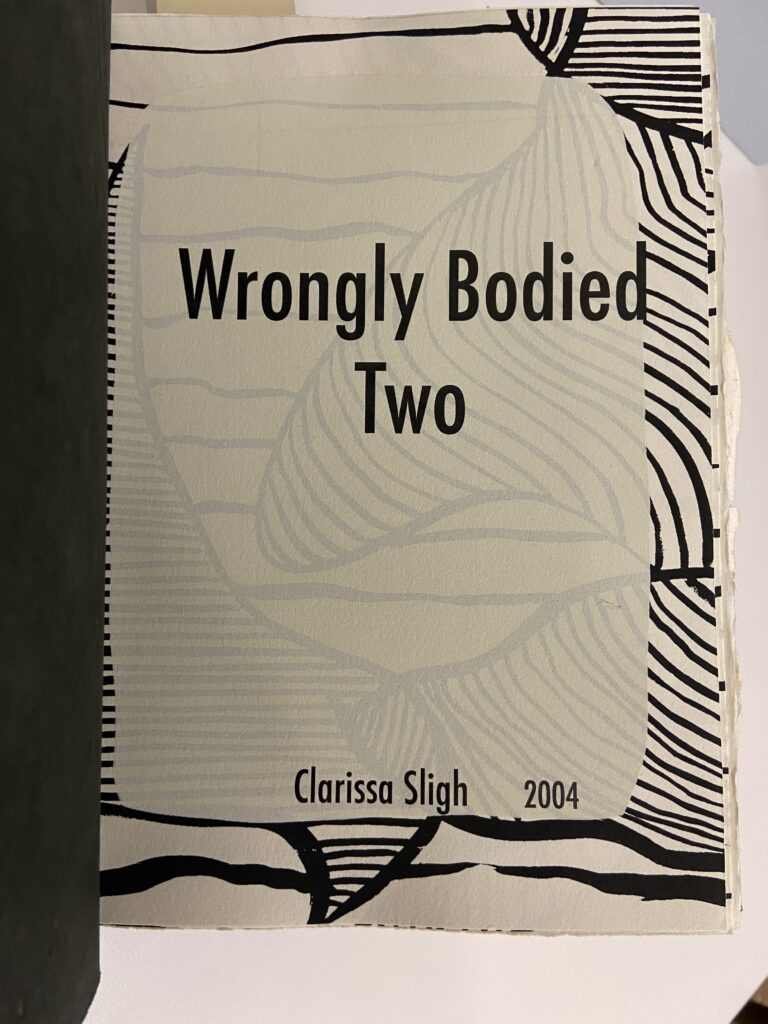

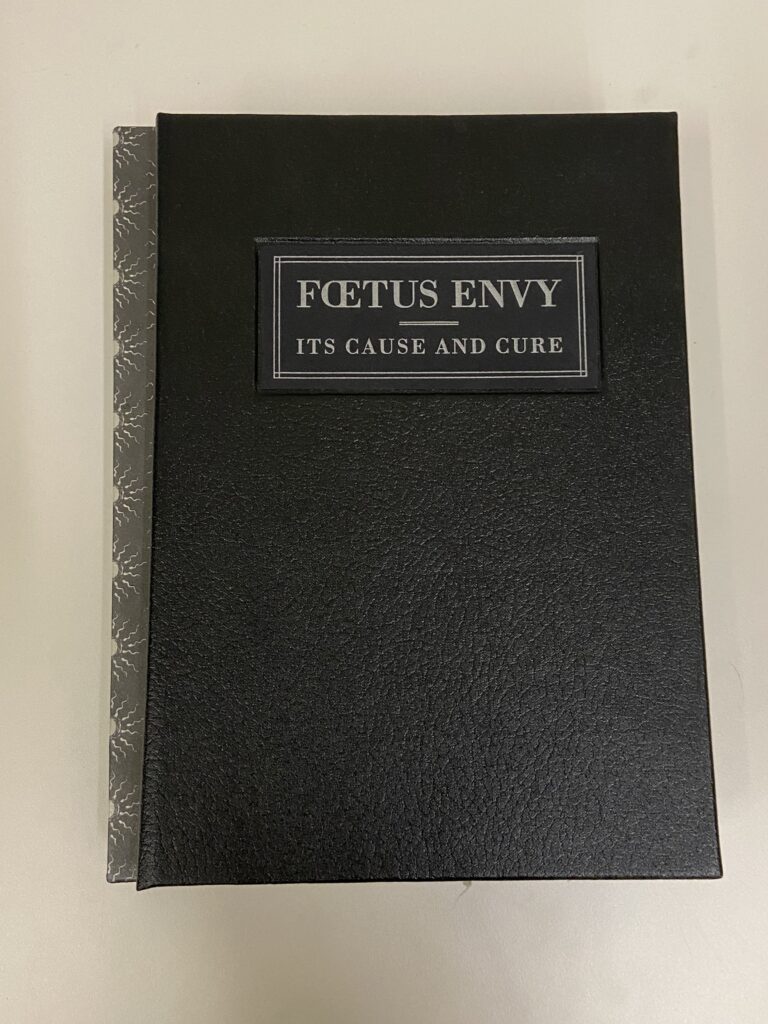

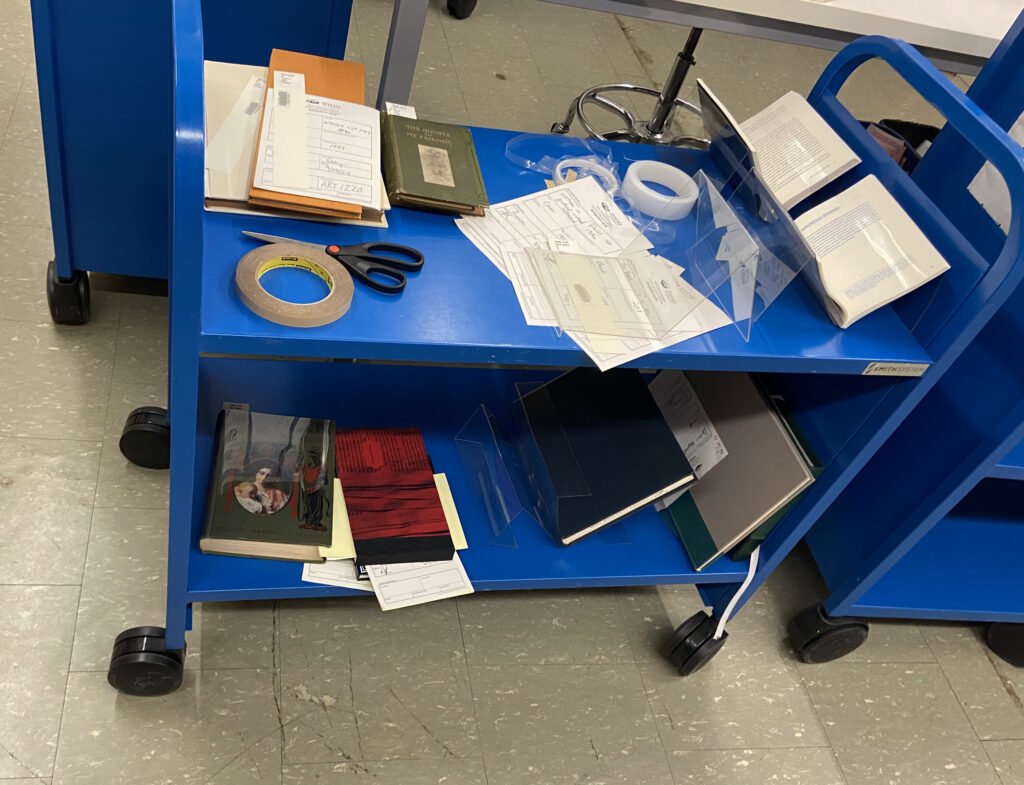

Pictured below are some of the books I considered adding to my display, but couldn’t due to space and/or for the sake of clearer focus. From left to right: This Thy Body by Ada Elizabeth Jones Chesterton, Frankenstein by Mary Shelley illustrated by Lynd Ward; Wrongly Bodied Two by Clarissa Sligh, Foetus Envy by Maureen Cummins.

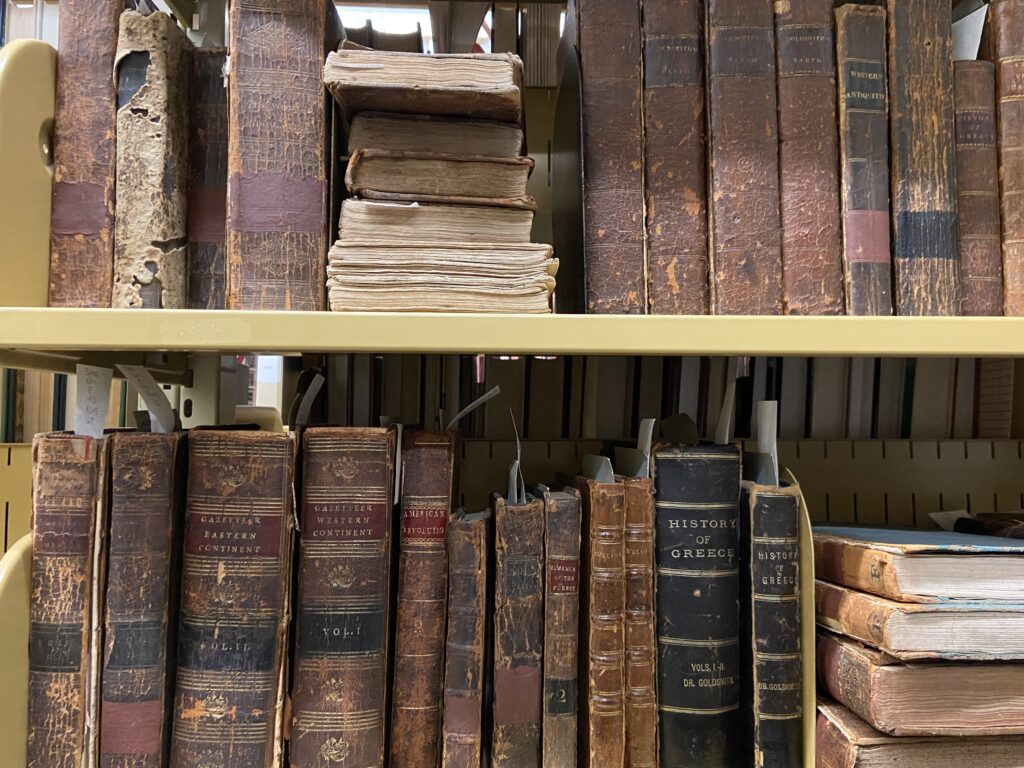

For my assistantship, however, I consistently work hands-on with a range of books. Some of these books are old, fragile, and require very careful handling—if you’ve ever held someone else’s newborn baby, then you can imagine holding one of these books.

So, with this in mind (as well as the fact that an exhibit does, it turns out, need to be visually interesting), I zeroed in on the physical components of books and bodies. Specifically, I wanted to think about physical frailty, mortality, and efforts at preserving and conserving books/bodies.

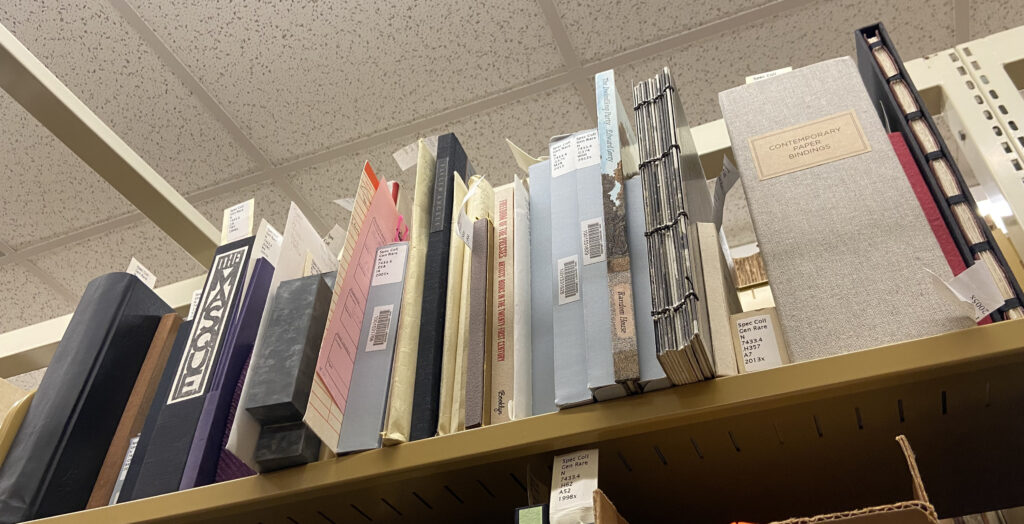

After settling on the topic, I began pulling books from my list, then evaluated whether I’d like to add them to the exhibit. My advisor, Special Collections Librarian Miriam Intrator, also suggested expanding upon my list by visiting shelving areas based on call numbers or subject. I found the visual aspect helped center my focus a lot, and browsing face-to-face ended up being the most effective process for finding the right materials for my exhibit. Though it can be time consuming and frustrating to pull a book, browse through it, and find that it doesn’t work, it’s just as exciting when a book that looks unpromising from the outside turns out to be a perfect fit.

I also found some materials completely incidentally, like Al Mutanabbi I by Elsi Vassdal Ellis. When the majority of my exhibit had been planned, I was pulling materials for an English class. I meant to grab a different artists’ book for that class when Ellis’s book fell over on the shelf. Fortunately, I decided to look through Al Mutanabbi I, and I knew pretty immediately that I wanted to add it to my exhibit for its focus on the sociopolitical dimensions of embodiment, mortality, and our treatment of (certain) books as cultural artifacts.

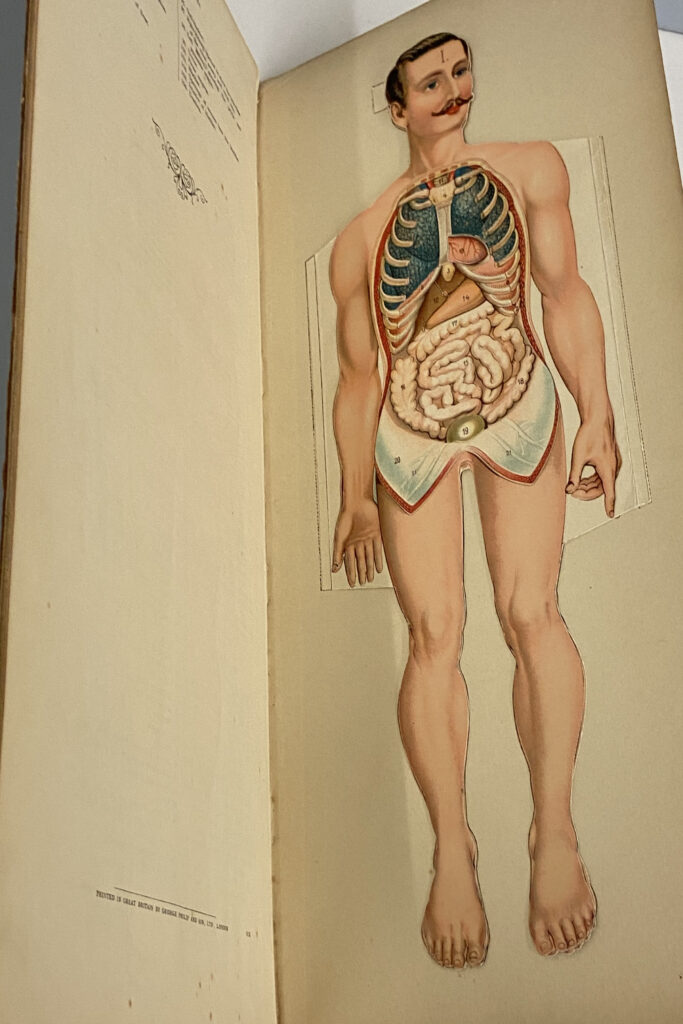

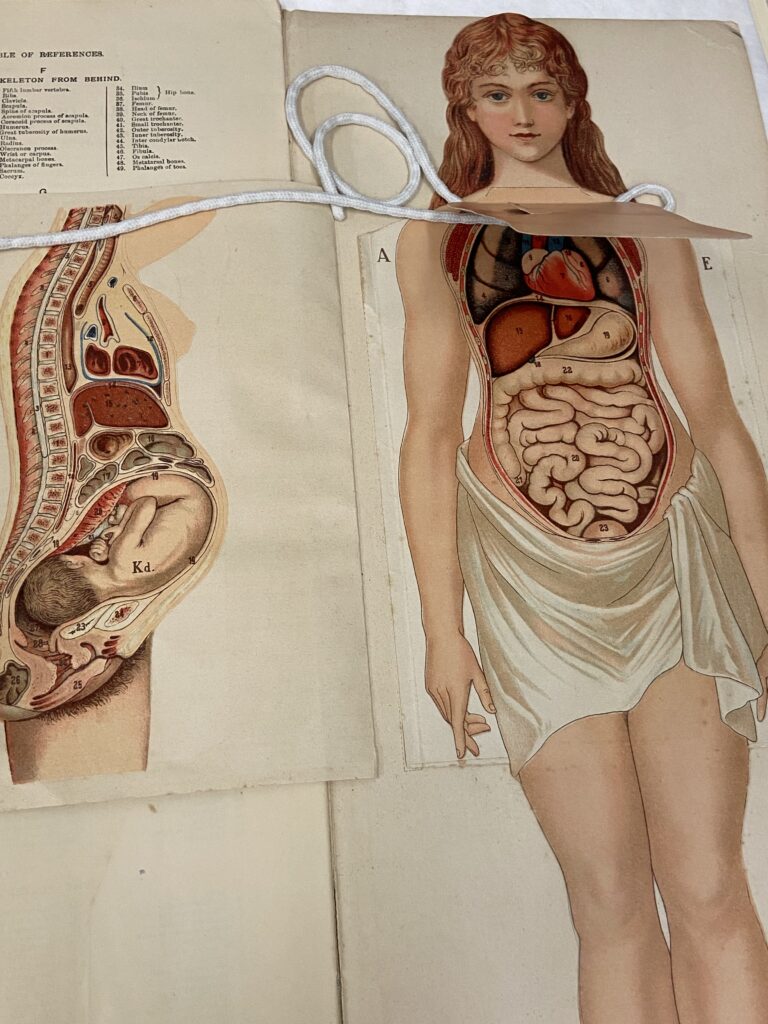

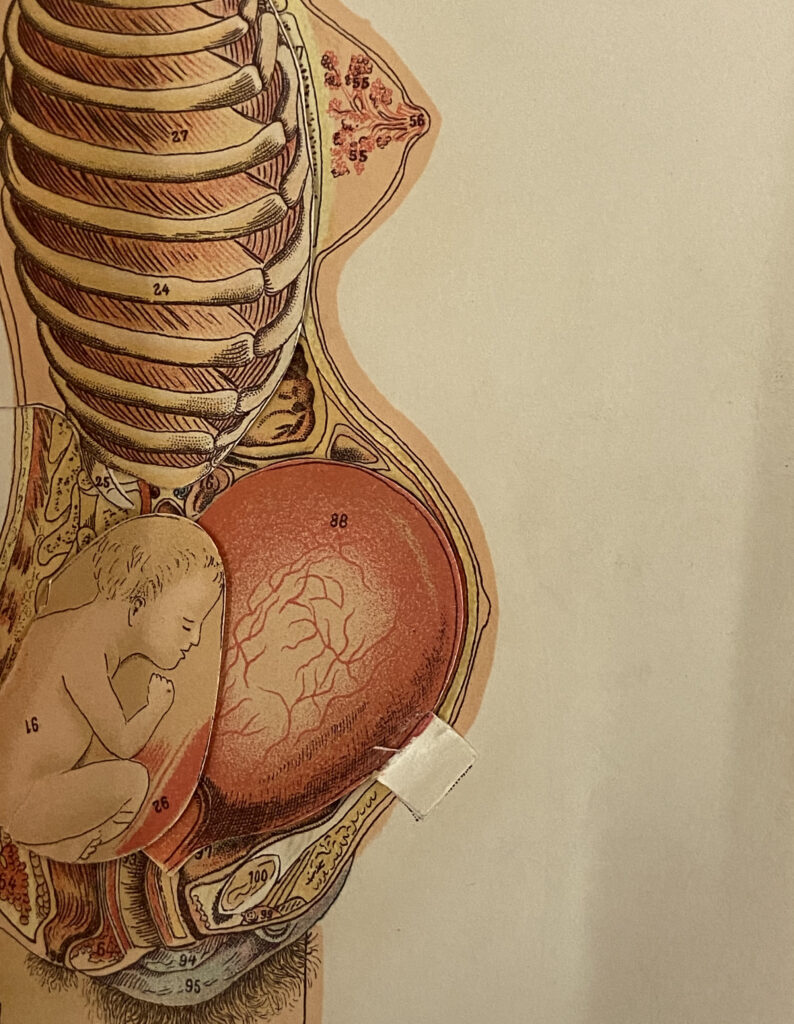

Just as human bodies influence the legitimacy given to (and ultimately, the survival of) certain books, the same dynamic appears between the information recorded in books and the bodies they depict. As I continued to browse scientific and anatomical texts for my exhibit, it felt almost remarkable how deeply invested these books were in legitimating certain bodies; when an anatomical model would have a fleshy counterpart, you could almost always bet they would be lily-white, thin, and very deliberately gendered.

(male left, female right).

I’m well aware that I’m by no means the first person to notice this or point out these issues, but I think there’s something to be said about the fact that even in these pretty rigid models of the body we have, for example, “Philip’s…model of the human body” and “Philip’s…model of the female human body,” as if certain descriptors (e.g. “male”) can be disregarded and subsumed under “human,” but others are apparently important modifiers.

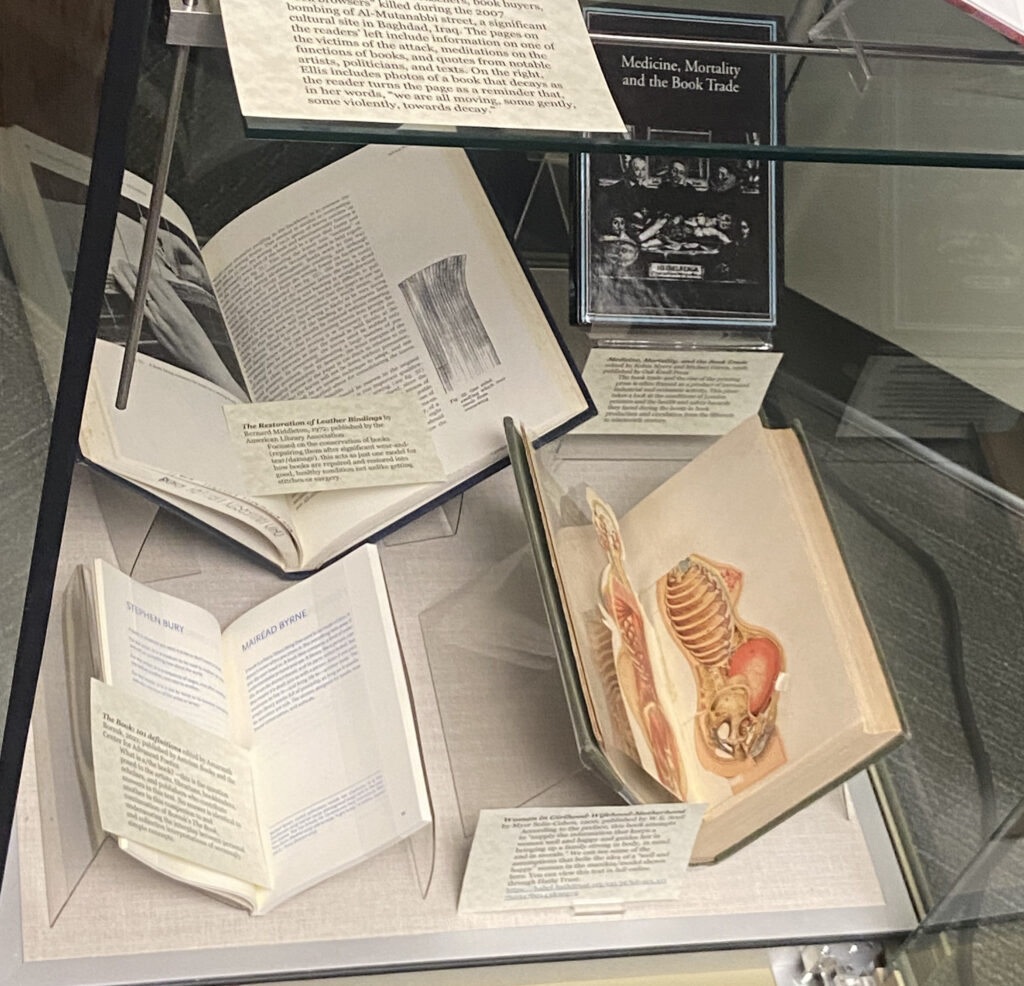

After some deliberation, I settled on including these materials in my display:

- Exquisite by Ann Lovett

- The Ghosts of my Friends (fully digitized!) by Cecil Henland

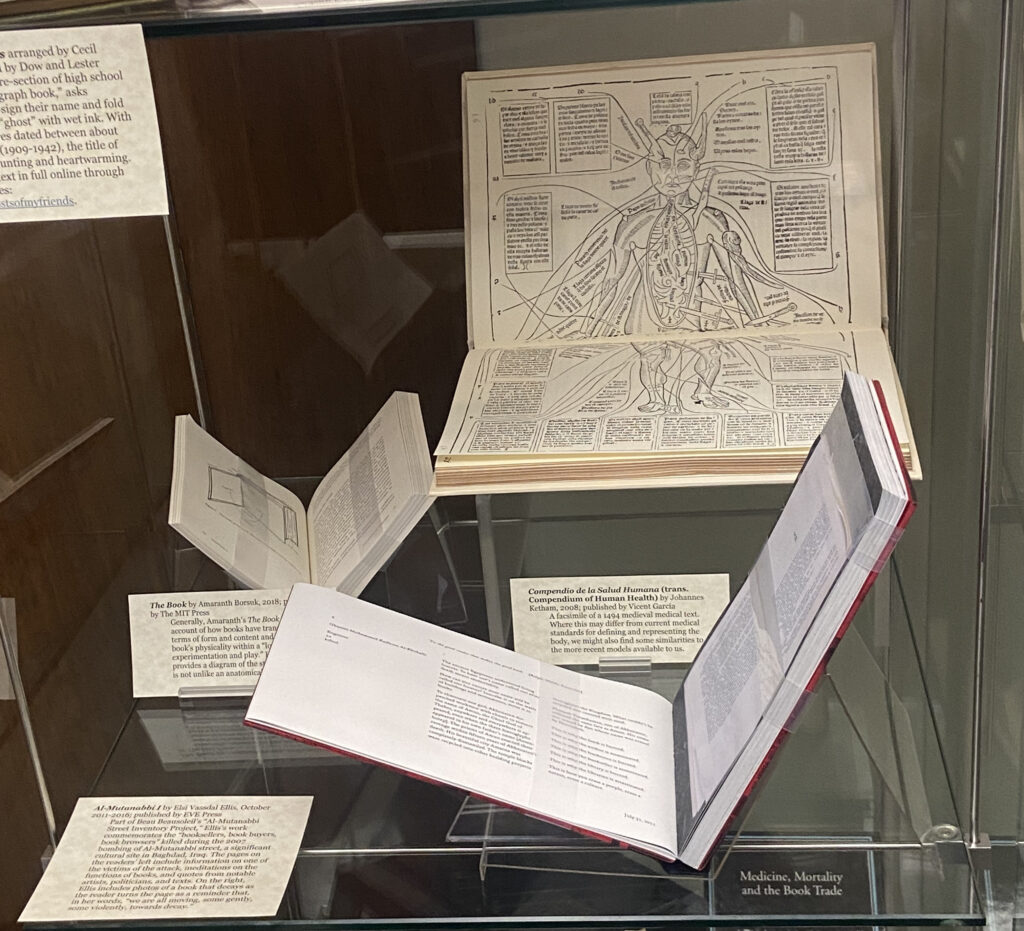

- The Book: 101 definitions edited by Amaranth Borsuk

- The Book by Amaranth Borsuk

- Compendio de la salud humana by Joannes de Kethan

- Woman in Girlhood-Wifehood-Motherhood by Myer Solis-Cohen

- The Restoration of Leather Bindings by Bernard C. Middleton

- Medicine, Mortality, and the Book Trade edited by Robin Myers and Michael Harris

- Al-Mutanabbi I by Elsi Vassdal Ellis

As far as getting the books from cart to exhibit, I’m indebted to Miriam and her experience maneuvering around the display case’s spatial limits. Until we started putting the materials on display, I hadn’t noticed a lot of the minute, near-invisible details (mainly special materials for exhibits) that go into making a very curated display look completely effortless—and, to maintain the illusion, I won’t spoil those secrets!

Before this assistantship, I hadn’t done a project like this, so it was a learning experience from beginning to end. This project also required me to think through questions I’ve had about texts and embodiment from a different angle, which was possibly the most challenging aspect, but definitely the most rewarding. Ultimately, I had a lot of fun putting this puzzle together!

To see the exhibit in person, you can find it inside Archives & Special Collections on the 5th floor of Alden Library through the spring semester.