By Jack Slemenda, Journalism ‘25, for JOUR 4130 Gender, Race, and Class in Journalism and Mass Media with Victoria LaPoe, Fall 2024

During the fall 2024 semester, the staff of the Mahn Center for Archives and Special Collections worked intensively with Victoria La Poe’s JOUR 4130 class, Gender, Race, and Class in Journalism and Mass Media. The students explored, selected, and researched materials from the collections, then worked in small groups to prepare presentations. The students had the option to then expand their research into a blog post like this one for their final project.

The book titled “Ohio Newspapers: A Living Record” encompasses a collection of reproductions of historic newspaper clippings that recount a variety of important moments in Ohio press history, like the creation of the first newspaper (Publick Occurrences) in 1690 to the emigration of Indigenous people from Ohio in 1843. Specifically, four different clippings provide a glimpse into the hardships experienced by Indigenous people which can be further analyzed by some of the theories studied in JOUR 4130.

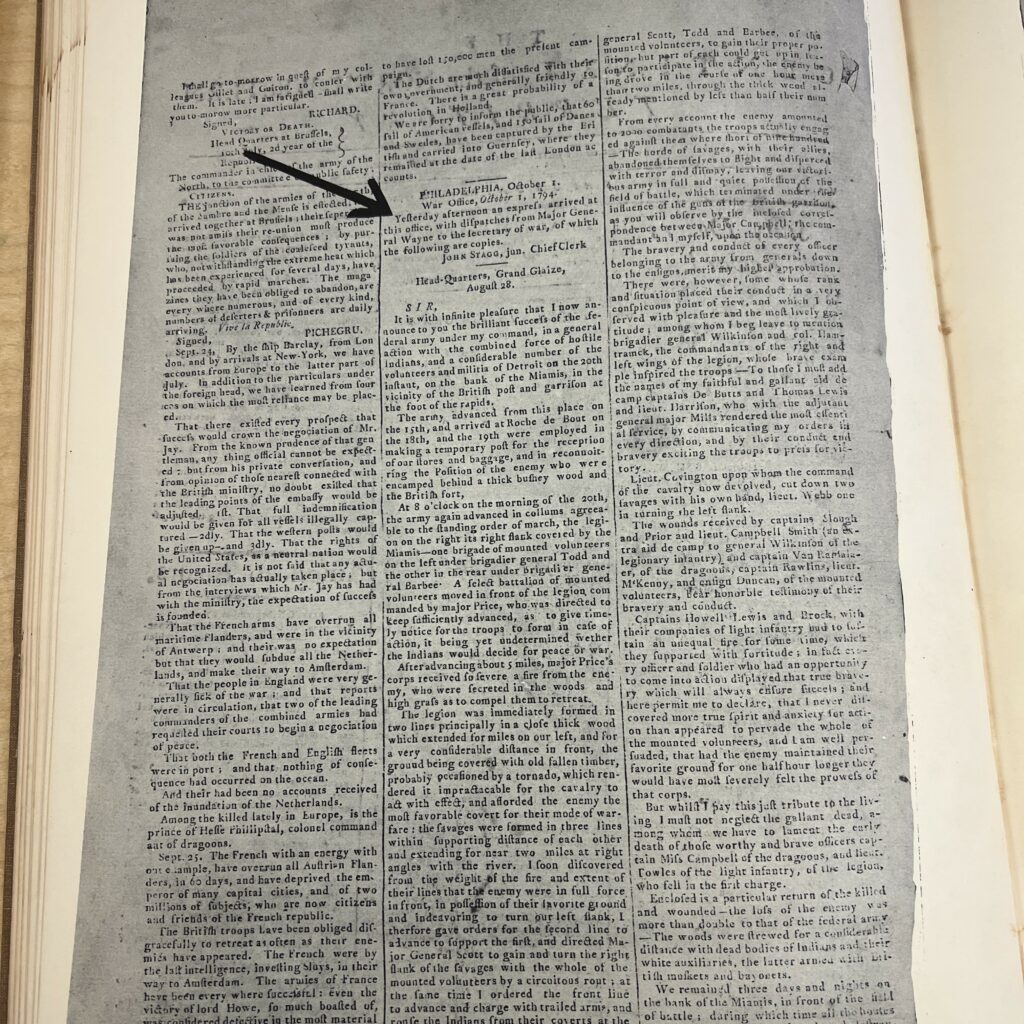

Clipping 1: The Battle of Fallen Timbers – Gatekeeping Theory

The first clipping I’m highlighting from Ohio Newspapers: A Living Record was originally published in 1794. It comes from an old newspaper called the Centinel which was based in Cincinnati, Ohio. This issue of the Centinel went into great detail about the Battle of Fallen Timbers that had recently ended. However, the Centinel’s coverage of the battle fell victim to something called gatekeeping theory.

Gatekeeping theory, as it pertains to journalism, is when the press deliberately filters content to push a certain agenda or idea to their audience. Unfortunately, this theory appears in the Centinel’s reporting of the Battle of Fallen Timbers. The general blueprint of the article in question only uses quotes or information on the battle from the perspective of the white soldiers fighting the Indigenous people, in this case, it was the Miami tribe. Secondly, the language used by Major General Wayne in his letter to the Secretary of War, Henry Knox, overly praised the swift and gruesome win he and his men experienced over the Miami tribe.

The fact that the Centinel did not include information on how demoralized and upset the Miami tribe was after losing another significant portion of their ancestral land, and only included the wording expressed in Wayne’s letter, is a blatant example of gatekeeping theory. The Centinel knowingly withheld the Indigenous people’s perspective to continue to feed into the preconceived notion that Indigenous people were barbaric and unruly.

Clipping 2: Indian Scalps Bring Reward – Indigenous Standpoint Theory/Community & Violence

The second highlight, again from the Centinel, takes a step back and looks at the Indian Wars from a more general perspective rather than a specific battle, allowing today’s reader to see a second and very important theory.

This set of articles goes into great detail about the brutality shown by Indigenous people in defending their homelands as well as the hostility exhibited by the American pioneers. Both of these groups play an important role in understanding Indigenous people’s history and thus understanding Indigenous standpoint theory.

Standpoint theory refers to a group of people’s position in society based on their grappling for power through politics and social encounters. This applies to Indigenous people because it refers to the ground that they stand on as people today knowing what their history entails with the violence and oppression they faced and oftentimes still face in our world today.

Through historical articles like these, we see Indigenous people forced to meet people where they are in a way. While they do hold a violent history it is important to understand why that violence was used as they attempted to defend their homes from aggressive foreigners looking to expand. As we know today, Indigenous people were forced to sign treaties pushing them further and further west as America continued to grow. This is an important notion to comprehend as we look at our third and final theory.

Clipping 3: Moccasins Moving West – Fourth Estate Theory/Political Policy

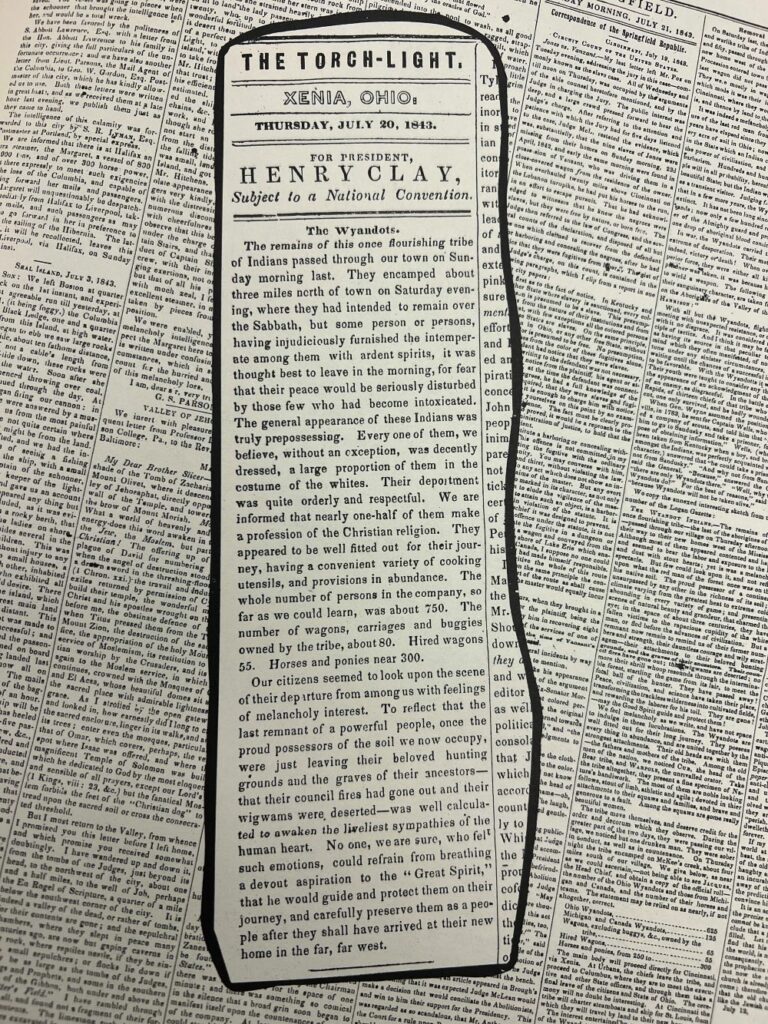

A publication in Xenia, Ohio called the Xenia Torch-Light finally moved past the preconceived idea of diminishing Indigenous people for who they are and how they acted in the Indian Wars in 1843. While what they reported in one of their issues was still a sad story for Indigenous people and their culture, it was at least the truth no matter how sad it was.

The Xenia Torch-Light clipping reads, “in 1825 there were in Ohio approximately 800 Shawnees, 550 Senecas, 540 Wyandots, 370 Ottawas, and 80 Delawares, and by the early summer of 1843 only the Wyandots remained.” … “By the fall of 1843 the Indian was gone from Ohio.”

Rather than focus on the number of American pioneers killed by Indigenous people during the Indian Wars, the Xenia Torch-Light wrote the truth with no additional interference through methods like advocacy, framing, or priming. Rather, the publication upheld the fourth estate theory of reporting the news without these types of interference by sticking to the number of Indigenous people removed from their homes.

As previously mentioned, the story told in this article is a sad one but a true one. However, considering the piece of policy that was the driving factor of the Xenia-Torch Light article, it was a pretty easy feat to uphold the fourth estate. The Indian Removal Act of 1830 was a piece of political policy pushed upon Indigenous people after all the fighting had ceased. Many different versions of this policy were signed depending on the tribe and the location of their ancestral lands.

Take the Wyandots as an example, they signed a treaty that forfeited nearly all of their lands barring 3.5 acres which contained a meeting house and burial ground. While it is somewhat refreshing to see a historical newspaper uphold an important pillar of journalism today in the fourth estate theory, it is not something to be overly celebrated as the piece of harmful policy that was in place was fueling the story more than anything else.

The treaty the Wyandots of Sandusky, Ohio signed goes so far beyond just their ancestral lands. The Wyandots, like many other Indigenous tribes across America in those days, were forced to pay out of pocket for their travel to their new lands, rebuild their settlements with little to no help from the government, and wait several years post-removal for annual financial help. An master’s thesis from 1965 titled “The Wyandot Indians of Ohio in the Nineteenth Century” by Martha Bowman explains all of this and goes into further detail about what happened to the Wyandots post-removal.

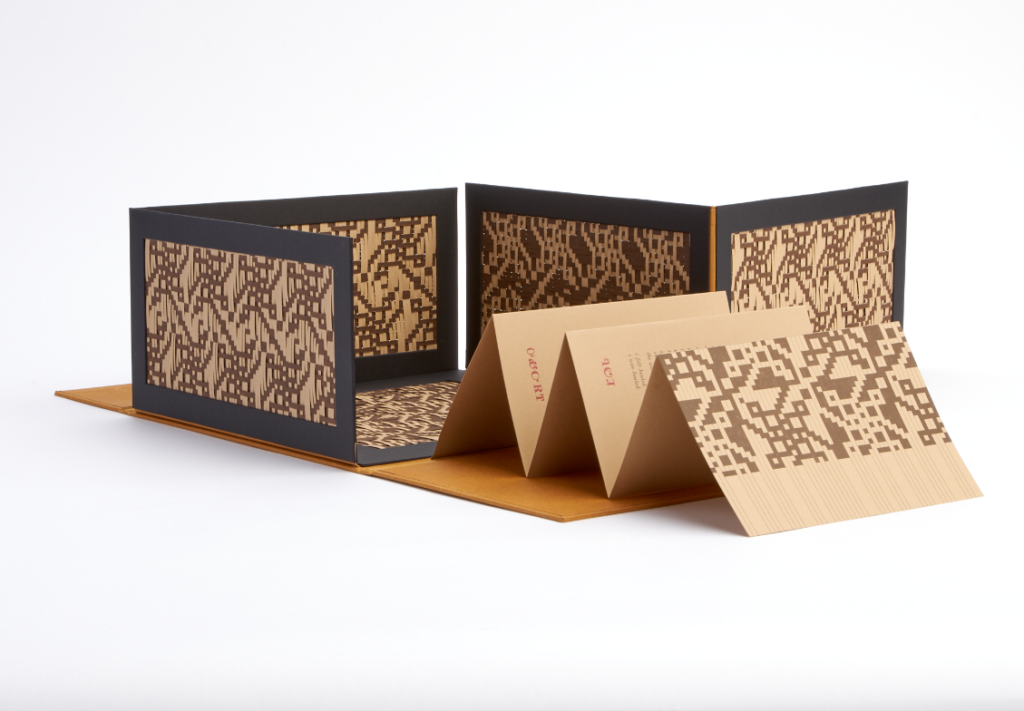

Additionally, to read a story I wrote about Ul’nigid’, a contemporary Eastern Bank Cherokee and Santa Clara Pueblo handmade, limited edition, artists’ book that is now available through Ohio University Libraries, find it online in The New Political.

References:

Library of Congress. (n.d.). The National Republican (Washington, D.C.), 1860-1888. Retrieved from https://www.loc.gov/item/sn84024486/

Mass Communication Theory. (n.d.). Gatekeeping theory overview. Retrieved from https://masscommtheory.com/theory-overviews/gatekeeping-theory/

Shelby County Historical Society. (n.d.). The Miami Indians. Retrieved from https://www.shelbycountyhistory.org/schs/indians/miamiindians.htm

PubMed Central. (n.d.). Article PMC11046738. Retrieved from https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11046738/

Library of Congress. (n.d.). The Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), 1854-1972. Retrieved from https://www.loc.gov/item/sn83045215/

Zimmerman, K. A. (2022). What is the fourth estate? ThoughtCo. Retrieved from https://www.thoughtco.com/what-is-the-fourth-estate-3368058

Library of Congress. (n.d.). Indian Removal Act of 1830. Retrieved from https://guides.loc.gov/indian-removal-act#:~:text=The%20Indian%20Removal%20Act%20was,many%20resisted%20the%20relocation%20policy

Oklahoma Historical Society. (n.d.). Wyandot Indians. Retrieved from https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry?entry=WY001#:~:text=During%20the%20early%201700s%20most,north%20of%20the%20Ohio%20River

OhioLINK. (2022). A qualitative analysis of [topic]. Retrieved from https://etd.ohiolink.edu/acprod/odb_etd/ws/send_file/send?accession=bgsu1670603448494077&disposition=inline

The New Political. (2023). Skye Tafoya’s “Ulnigid”: It means strong. Retrieved from https://www.thenewpolitical.com/news/skye-tafoyas-ulnigid-it-means-strong