By Alex Hetrick, Communication Studies ‘25, Anthony Bray, Journalism News and Information ‘25, Cameron Voelker, Journalism Strategic Communication ‘25, and Matthew Nichols, Journalism ‘25, for JOUR 4130 Gender, Race, and Class in Journalism and Mass Media with Victoria LaPoe, Spring 2025

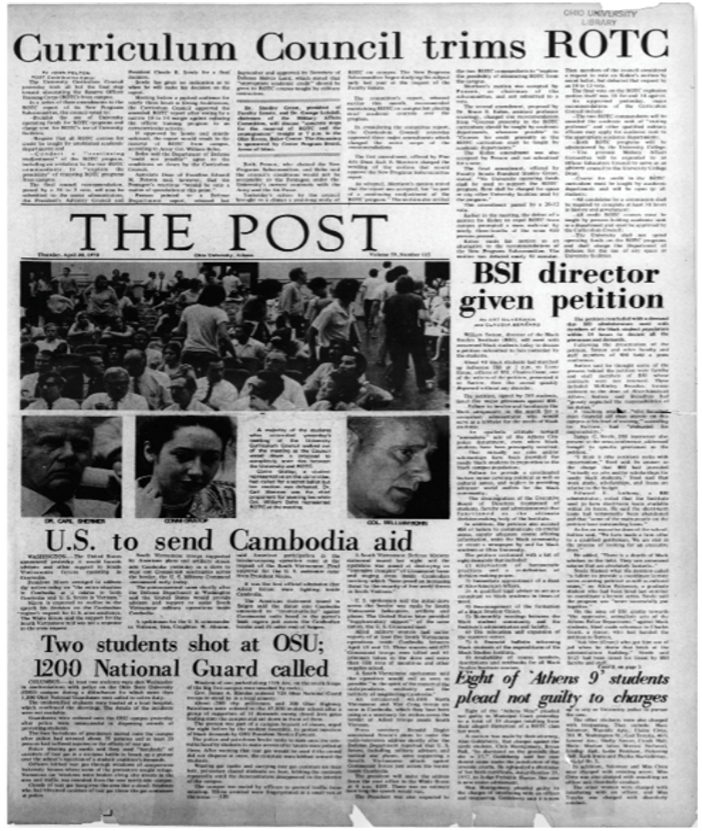

By the spring of 1970, Ohio University students had endured years of growing unrest tied to the Vietnam War, with rising frustration over the military’s presence on campus. The Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC) became a particular point of contention. On April 22, 1970, tensions escalated when nine students, eight of them women, were arrested for allegedly disrupting an Army ROTC class in Carnegie Hall (which is now known as Scripps). The group, later referred to as the “Athens Nine,” became a catalyst for a wave of student activism in Athens, igniting protests over both their arrest and the broader U.S. military involvement in Southeast Asia

The following day, April 23, around 50 students interrupted a meeting of the President’s Advisory Council in Cutler Hall. They protested the Athens Nine arrests and demanded the removal of the ROTC program from campus. Though the demonstration remained peaceful and students eventually dispersed, it signaled a campus on the brink—what had started as isolated acts of protest was quickly growing into a larger, more organized movement.

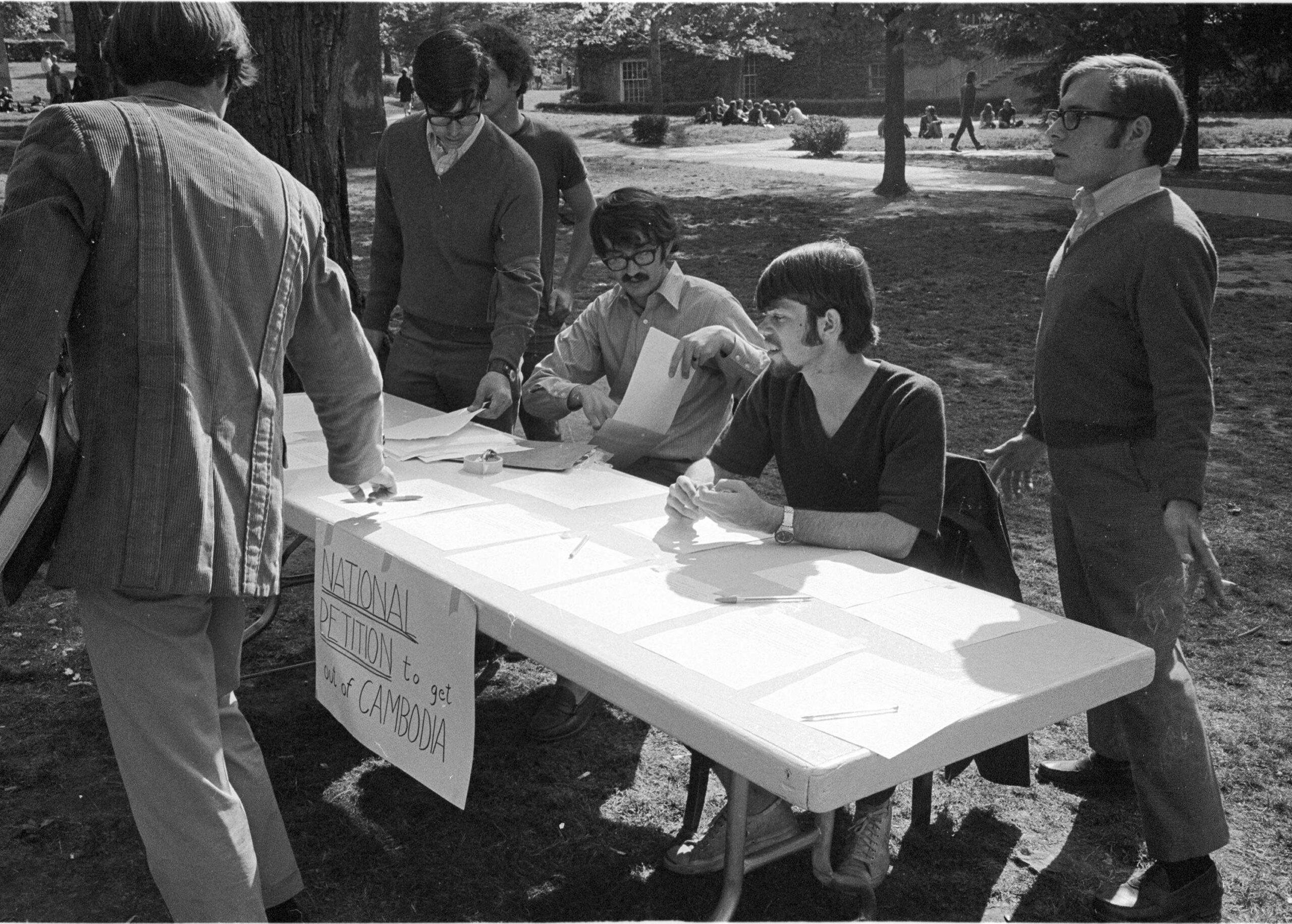

When President Richard Nixon announced the U.S. military expansion into Cambodia on April 30, 1970, the decision sent shockwaves across the country, and Ohio University was no exception. The Athens campus, already simmering with anti-war sentiment, quickly became a center of unrest. In the days that followed, protests intensified across the campus, uniting students, faculty, and even locals in a wave of both peaceful and violent demonstrations.

USA Today

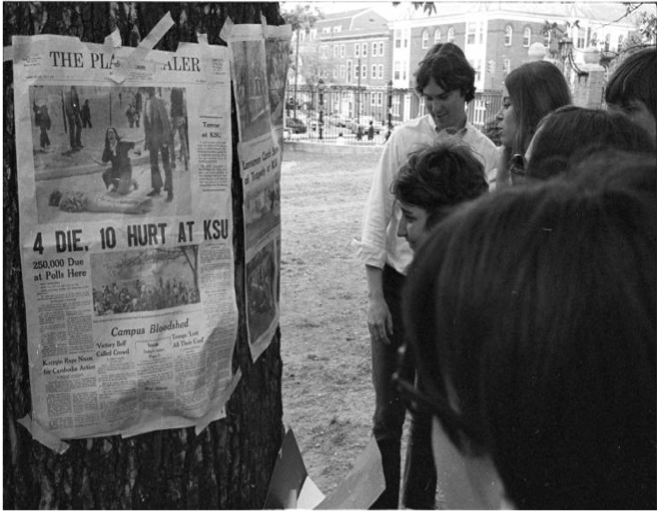

Just days after Nixon announced the invasion of Cambodia, the nation was shocked by the tragic events at Kent State University on May 4, 1970. During a student-led antiwar protest, members of the Ohio National Guard opened fire on unarmed demonstrators, killing four students and wounding nine others.

The shootings stunned the country and immediately became a pivotal moment in the national conversation about free speech, civil disobedience, and the Vietnam War. For students across Ohio and the nation, the incident deepened a sense of fear, anger, and urgency. Protests that had already been building in response to Nixon’s policies now took on new meaning, focusing not only on war abroad but also on the violence erupting at home. The Kent State shootings symbolized the growing divide between young people and authority, and they compelled a generation to demand accountability and change.

In the early hours of May 7th, the unease at Ohio University jolted to life when two firebombs thrown into the ROTC supply room inside Peden Stadium caused an estimated $4,000 in damage to uniforms and the structure. This act of arson marked a new level of intensity in student protests.

University President Claude Sowle calmly condemned the violence, declaring that “OU must remain open.” Yet by mid-morning, his resolve faced a sobering reality when Governor James Rhodes informed him that neither the National Guard nor the Highway Patrol would provide support should the tensions escalate

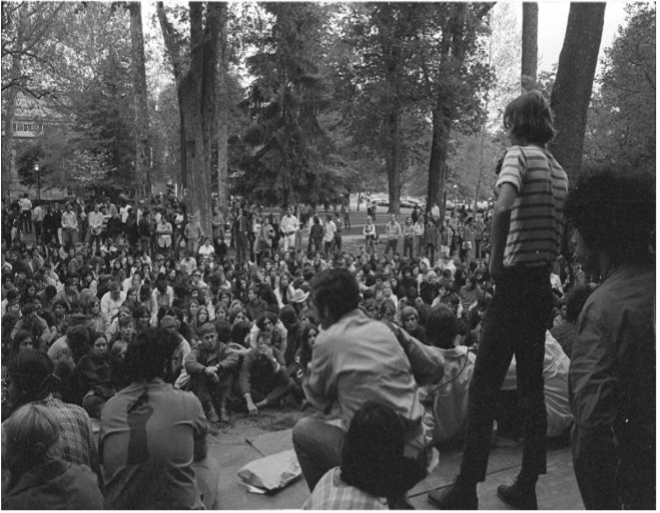

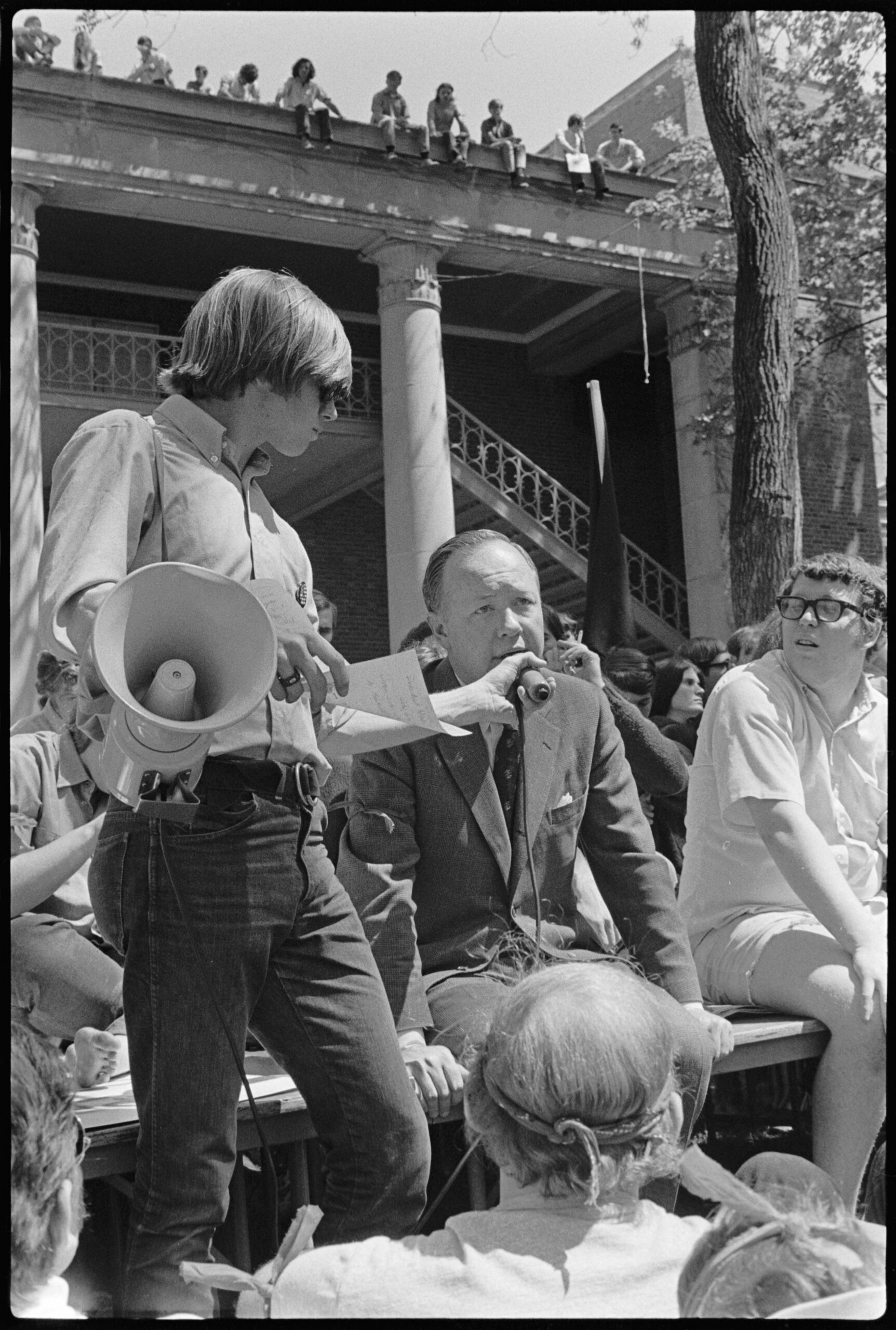

Later that day, as anti-war energy swept campus and downtown Athens, nearly 30 local businesses closed their doors amid renewed calls from student demonstrators urging solidarity with the national student strike. That evening, after a large rally on College Green, approximately 400 students blocked the intersection of Court and Union. With assistance from university marshals and police from Athens, Belpre, and Logan, the crowd was peacefully dispersed by 1 a.m. despite a denied renewed request for backup from state authorities.

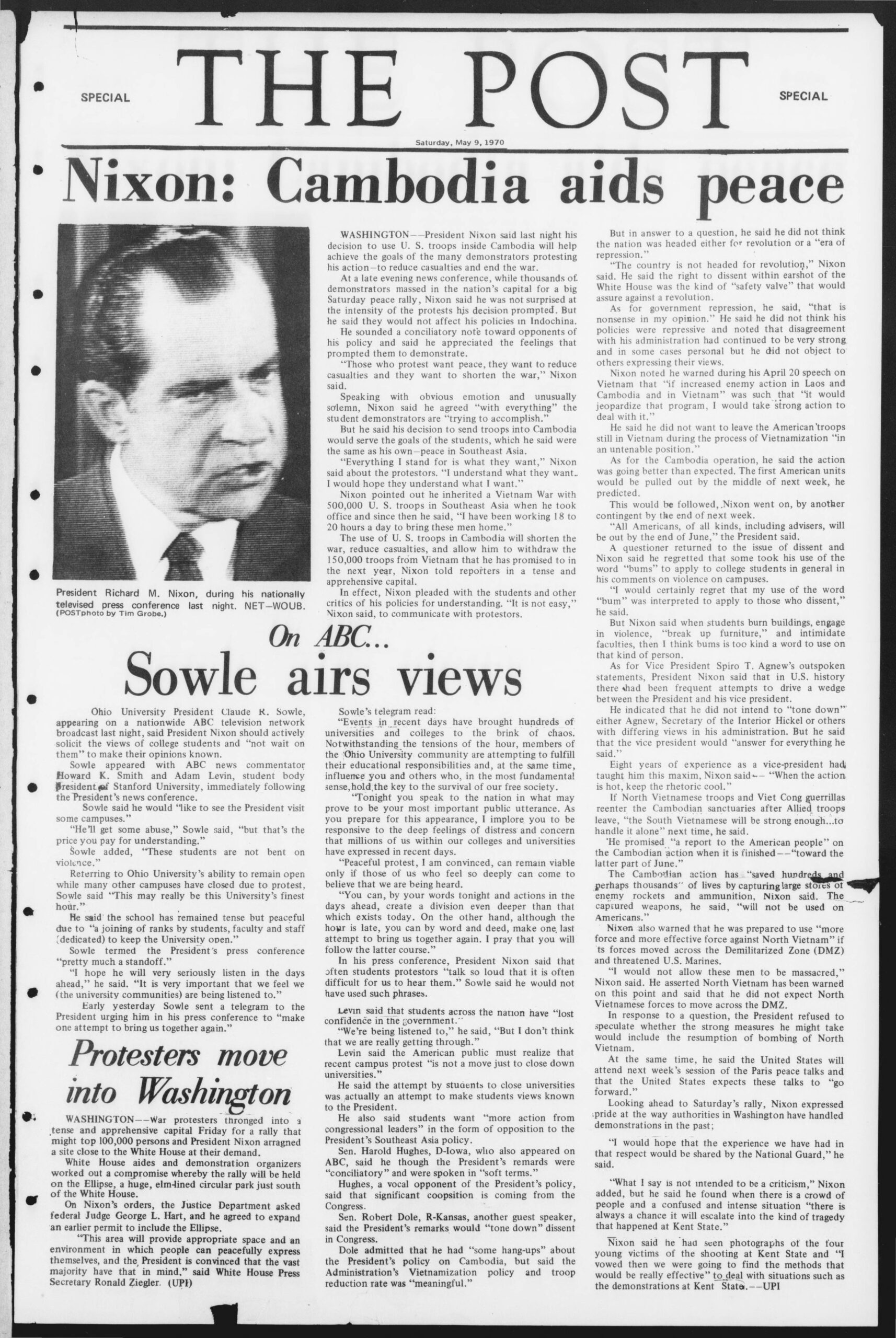

On May 8, President Sowle reiterated his commitment to keeping the university open, crediting the resilience of the campus community. “My continuing faith is based in large part upon the magnificent response of our students, faculty, and staff,” he said. That night, he traveled to Washington, D.C., to appear on ABC’s national panel, following President Nixon’s press conference on Cambodia.

The weekend passed quietly, and a cautious optimism settled in on OU’s campus. But by Monday, May 11, Ohio University braced for what would become its most turbulent stretch in history. The next morning, more than 3,000 students filled the Grover Center gymnasium for a rally featuring John Froines, a member of the Chicago Conspiracy Eight. Later around 11 a.m., a group of roughly 100 students broke into the vacant former Chubb Library, declaring it a “Free University” and occupying the space in protest.

The stress deepened in the early hours of May 12. At 1:30 a.m., another firebombing struck the new addition to Nelson Cafeteria and an adjacent dormitory still under construction. Damages soared to $150,000, though the properties had not yet been transferred to university ownership. With requests for highway patrol assistance again denied, city and university police surrounded the occupied former library building at dawn. The students inside were offered the choice to leave or face arrest. By 6 a.m., all but about 30 exited quietly, and no confrontation followed.

That evening, a campus curfew was imposed as unrest continued. About 75 students gathered inside Baker Center, drafting a formal list of demands which was delivered directly to President Sowle’s Park Place residence. As campus stood on edge, one thing became clear: the events unfolding at Ohio University reflected the broader national crisis, a generation demanding change, and a university caught between the pressure to maintain order and the call to listen.

As tensions continued to escalate on campus, Ohio University administration took a more aggressive stance. On May 13, 1970, President Claude Sowle announced the indefinite suspension of seven students, citing them as a threat to the university’s orderly functioning. Notably, two of those suspended weren’t even enrolled in spring quarter classes but lived near campus, reflecting the administration’s broad approach to what it saw as a destabilizing presence. The suspensions further inflamed student frustration, particularly among those who viewed the actions as punitive and vague in justification.

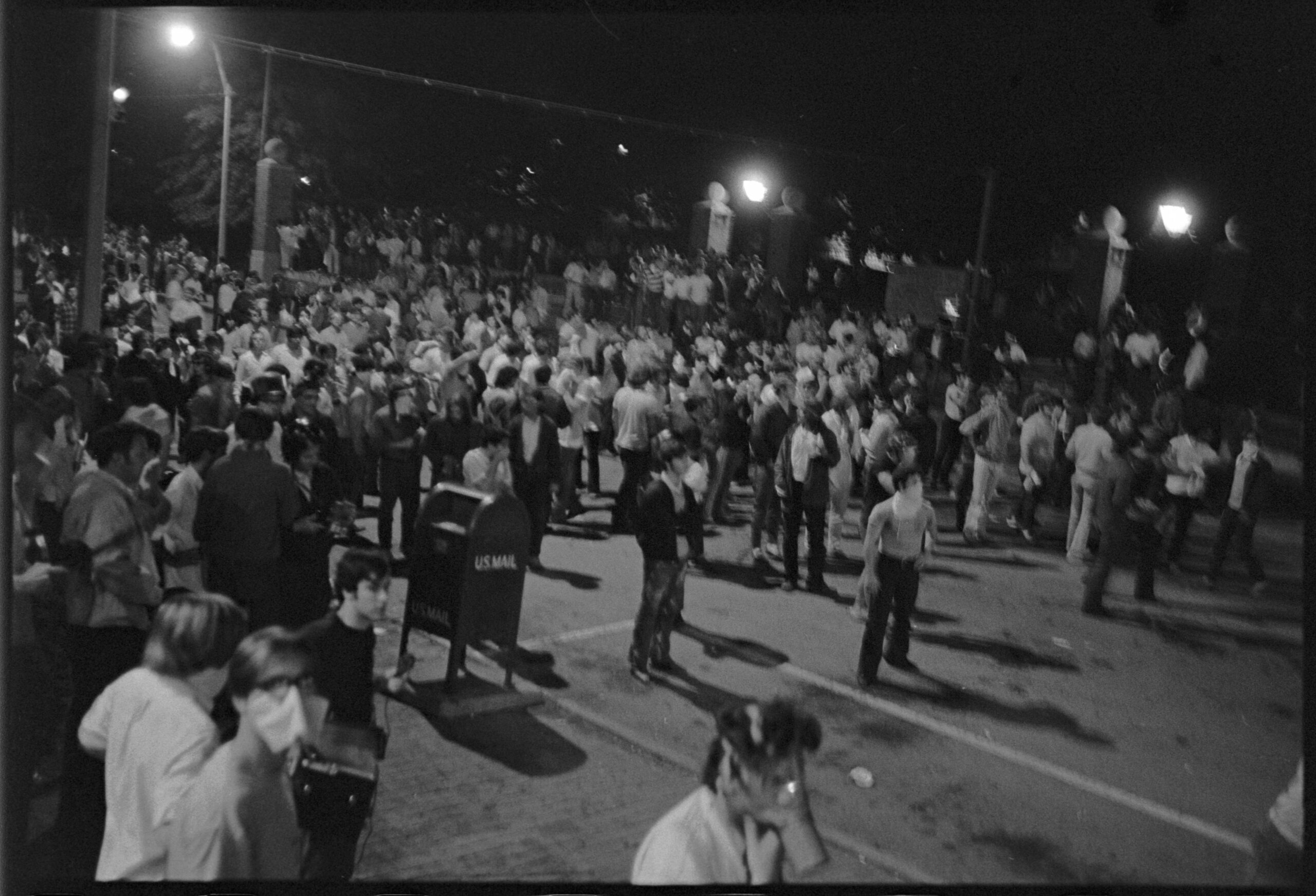

Just hours later, in the early morning of May 14, approximately 250 students gathered at the intersection of Court and Union Streets. What began as a demonstration quickly turned violent when bricks were tossed into the windows of Logan’s Bookstore. Police responded with tear gas and pepper fog, initiating a confrontation that lasted nearly an hour. While the area was cleared by dawn, the unrest was far from over. By mid-morning, a crowd of nearly 700 had returned to the same intersection, and violence resumed. More tear gas was deployed, students threw bricks and bottles, small fires were lit, and parking meters were destroyed. Student marshals attempted to calm the crowd but were overwhelmed. When the chaos finally settled, 54 students had been arrested, and the sense of control on campus had all but vanished.

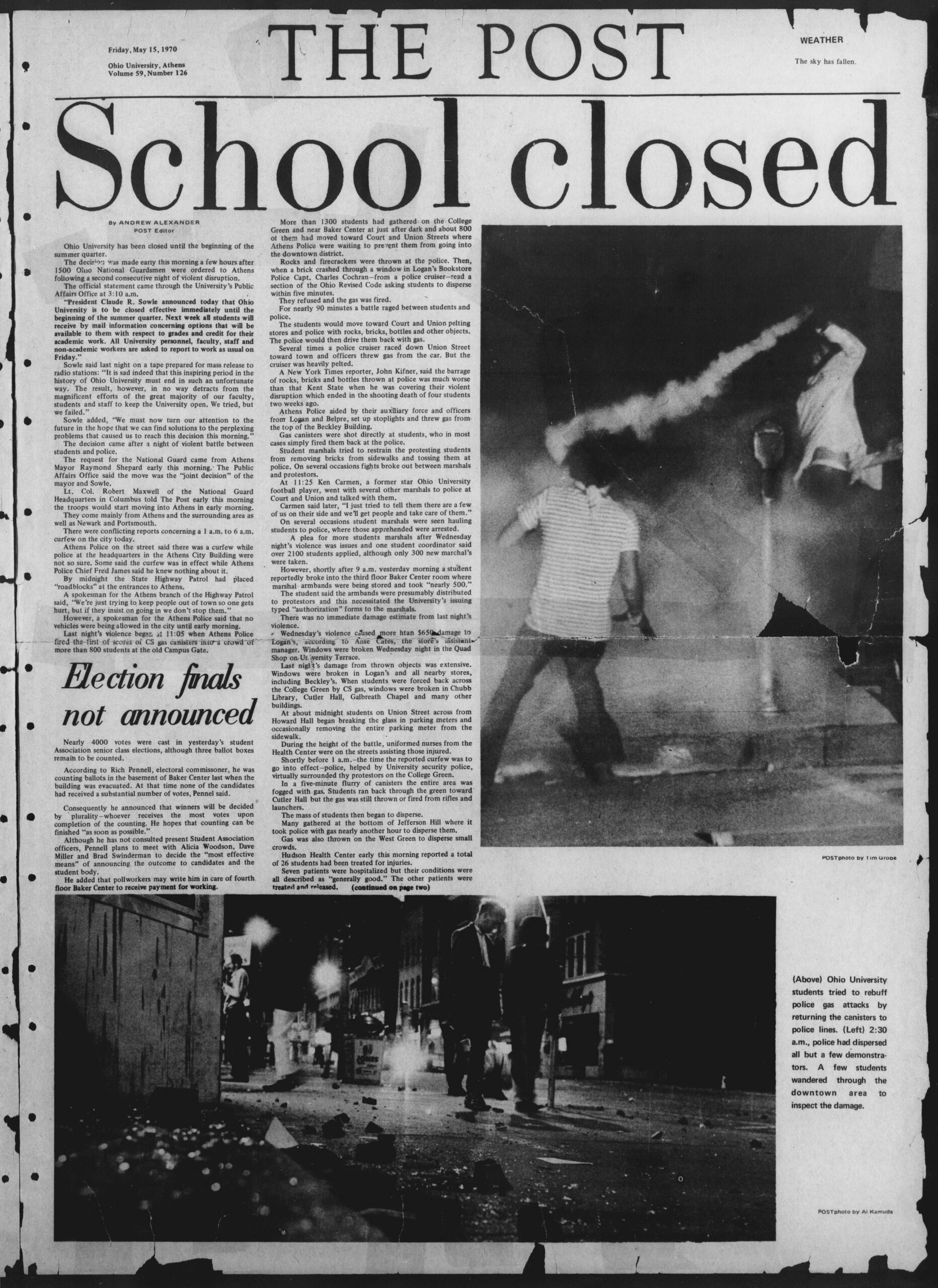

At around 3AM on May 15, President Sowle made the decision to shut down Ohio University indefinitely, following an overnight clash that had resulted in $154,000 in damages. Governor James Rhodes had already deployed the National Guard, and by morning, students were ordered to vacate campus. It was a historic moment—one of the few times a major American university had been forced to close due to civil unrest. The shutdown signaled the peak of tension in a month-long confrontation between students and administration, between protest and power.

But the summer brought a shift in tone. On June 3, President Sowle addressed the university community with a letter proposing a path forward. He called for a workshop to be held June 8–11, aiming to repair campus trust and chart a course for healing. Students, faculty, and administrators came together to discuss how Ohio University could reaffirm its mission as an academic institution and respond to the legitimate grievances voiced during the protests. The workshop didn’t erase what had happened, but it marked the first step in transforming unrest into reflection—and eventually, reform.

Visual agenda setting suggests that powerful images can shape public perception and influence behavior by making certain issues more visible. Ohio University students reacted to images published by The Post with protests and other movements. Photos of other protests going on around the country, such as the ones at Kent State, caused unrest amongst the Ohio student body. Each photograph shared by the media pushed students to act in different ways.

Agenda setting theory explains how Ohio University students placed anti-war sentiment at the forefront of campus consciousness through organized protests, sit-ins, and other acts against the administration. Different acts framed the war as a moral crisis that students demanded immediate attention for. The agenda reinforced the students’ actions, such as setting fire to Nelson Commons, and doing lots of damage to other University buildings.

Framing theory explains how the way an issue is presented can shape how people understand it. During the University protests, students framed the ROTC as a symbol of the Vietnam War, even though the ROTC was not responsible for combat. Because of how students framed the ROTC, students thought that their presence on campus was unacceptable and began protesting because of how they remained on campus. Students viewed the ROTC as military, and their presence on campus made the war feel like it was in Athens, making the student’s protests feel more personal and urgent.

Counternarrative theory focuses on challenging popular, mainstream stories by presenting alternative perspectives. During the protests at Ohio University, powerful photographs of protesters showed counternarratives to government claims of peaceful campus control. The visuals exposed the tension in between students and administrators and helped to shift the public perception of the students’ protests.

Public discourse theory emphasizes the importance of open dialogue in shaping societal values and decisions. During the protests, different student groups tried to directly engage with local officials and university administrators to voice their concerns about the presence of ROTC on campus as well as the Vietnam War. Even though the conversations were difficulty, different workshops and meetings allowed the students to voice their concerns to university administration.

Several other concepts help to deepen understanding of the 1970 Ohio University protests. One of these concepts is gaze, which looks at who is doing the watching, and who is being watched. Thinking about this from an Ohio University perspective, many of the reports and photos of the protests came from external observers, like law enforcement, or university officials. With this power dynamic, it skews the protests in a way that makes the protestors look disruptive instead of principled. When students were able to create their own media through photos and statements, they regained control over how their actions were portrayed.

Organizational constraints also played a large role in how information was shared. Student work, like publications and media on campus often received oversight from the university, especially after House Bill 1219 was passed. House Bill 1219 allowed for student suspension for those involved with campus disruptions, even before the judge legally convicted them. Students fearing legal consequences likely felt that they could not freely express themselves, especially in student media.

The idea of timing and the decisive moment help to answer why certain events stand out in memory. For the Ohio University protests, it helps answer why events like the May 15 shutdown are most remembered. Some of the moments from the protest became symbolic, not just because of what happened, but because of when they occurred and how they were captured. Documentation of events with photos and headlines gives events more weight and helps to shape the overall narrative.

Another idea to consider is institutional narrative, meaning how universities remember and tell stories about their own history. The way Ohio University recounts the events of 1970, whether that be through articles or archival collections, plays an important role in how the events are remembered. For instance, the university chose to highlight both the peaceful protests and the more violent ones- like firebombs and student arrests. The choice to show both sides helps understand the full scope of the events, instead of only showing the positive side. This reflection of events reflects not only the school in 1970, but the university in the present day as well.

On top of just public discourse, it is important to view the protests through the lens of performative communication. Whether it be campus meetings or President Sowle’s appearance on national television, these events showed concerns people had about war and student rights. They designed the protests to be seen, and gave students an avenue to express themselves when other channels did not work. Looking at the events with these themes helps us understand how communication and visibility played a role in one of the most important events in the history of Ohio University.

References

Tom Breeden, “Eyewitness to 1970 riots at Ohio University in Athens,” Chillicothe Gazette, August 21, 2022, https://www.chillicothegazette.com/story/opinion/columnists/2022/08/21/breeden-eyewitness-to-history/65406492007/.

“Countdown to the 1970 Closing,” OHIO Today, September 22, 2020. https://www.ohio.edu/news/2020/09/countdown-1970-closing.

Grace Dearing and Justin Thompson, “OHIO’s Class of 1970 looks back on a school year unlike any other,” OHIO Today, April 8, 2020. https://www.ohio.edu/news/2020/04/ohios-class-1970-looks-back-school-year-unlike-any-other?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

Emily Hall, “10 days of unrest: The 1970 Ohio University protests and closure,” The New Political, February 27, 2025, https://www.thenewpolitical.com/news/10-days-of-unrest-the-1970-ohio-university-protests-and-closure.

“It’s All About Timing,” Image Maven, https://www.imagemaven.com/blog/its-all-about-timing#:~:text=Photographer%20Henri%20Cartier%2DBresson%2C%20the,all%20intersect%20in%20perfect%20unison..

John Higgins, “1970 Campus Security Records Blog Series: The Green and White Badge of Courage,” OHIO Archives Blog, April 17, 2023, https://sites.ohio.edu/library-archives-blog/2023/04/17/1970-campus-security-records-part1/.

Jerry M. Lewis and Thomas R. Hensley, “The May 4 Shootings at Kent State University: The Search for Historical Accuracy,” Published in revised form by the Ohio Council for the Social Studies Review, Vol. 34, No. 1, Summer 1998, pp. 9-21, https://www.kent.edu/may-4-historical-accuracy.

Ohio University Board of Trustees Minutes, May 29, 1970, https://www.ohio.edu/sites/default/files/sites/trustees/files/1970%20May%20Minutes.PDF.

Ohio University Student Affairs, “History of Free Speech and Activism at OHIO,” https://www.ohio.edu/student-affairs/expression/history.

Ohio University, “Campus Disruption (Ohio House Bill 1219),” https://www.ohio.edu/student-affairs/students/notifications/house-bill-1219.