|

|

|

Lawrence M. Witmer,

PhD

Professor of Anatomy

Chang Ying-Chien Professor of Paleontology

OU Presidential Research Scholar 2004-2009

Dept. of Biomedical Sciences

Heritage

College of Osteopathic Medicine

Life Science Building, Rm 123

Ohio University

Athens, Ohio 45701 USA

Email:

witmerL@ohio.edu

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

Preface.—The purpose of this narrative is to describe my path

to academia. Its intent is

ostensibly to provide background for prospective students and my

professional friends and colleagues, and to acknowledge those people and events that have

influenced my professional development.

But beyond that, as my scientific mission has been to “flesh

out” animals of the past, so do I here seek to flesh out my own past.

Ultimately, it’s been fun to reflect on my own

evolutionary history for once and to assemble these thoughts. |

| The

early years.—I was born into a loving home in Rochester, New

York, in the late 1950’s, where, as the youngest of four children and

only boy, I probably was indulged more than was healthy (perhaps as

amply attested by the indulgence of this narrative).

Nevertheless, I had a happy and healthy middle-class suburban

upbringing. Like many

scientists of all stripes (and folks in general), my first exposure to

science was through the world of dinosaurs.

Unlike many scientists, my passion for dinosaurs and their kin

never waned. A very

important early influence was the traveling exhibit of life-size

dinosaur reconstructions put on by the Sinclair Oil Company (originally

part of the World’s Fair). Likewise,

the books of Edwin H. Colbert—Men and Dinosaurs, The Age of

Reptiles, etc.—were books I read over and over again.

I recently found my original copy of Roy Chapman Andrews’ All

About Dinosaurs, the classic account of the Central Asiatic

Expeditions; not only was it well-thumbed but (I shouldn’t admit it)

had highlighting and marginal notes.

Throughout my childhood, I studied other areas of science (how

could a child not have been captivated by the drama of the Gemini and

Apollo missions?) and even branched out into comparative literature, but

the evolutionary history of life on Earth was a consistent draw. |

|

|

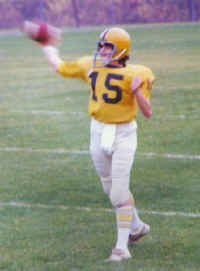

Of course, as adolescence advanced, my

interests strayed to sports, cars, and girls—although

I have to admit that I did better in the first two than

the third (I lettered in football, basketball, track,

and tennis, and my 1969 burgundy Firebird convertible

will never be matched). Nevertheless,

I managed to maintain sufficient academic focus to

graduate from James E. Sperry High School as

salutatorian in 1977.

I need to acknowledge the importance of my high school Earth

Sciences teacher—one of those unsung but pivotal

individuals one encounters in public school: Don Shultz

cultivated my interests in paleontology and introduced

me to the joys of amateur fossil collecting.

Mr. Shultz would routinely pull a fossil from his pocket and

offer that “If I could identify it, I could have it,”

where after I would run to technical sources and

discover the name of the beast. |

|

| Higher education.—In

the fall of 1977 I entered Cornell University in Ithaca, New York.

I started out as a Biology/Geology double major, but soon

realized that these majors were in different colleges, each of which had

formidable requirements. Always

(and still) a biologist at heart, I settled on biology.

Nevertheless, I still took all the “soft rock” courses in the

geology department, and John Cisne (Cornell’s invertebrate

paleontologist) was a big influence, as was paleobotanist Karl Niklas.

Without question, the most important course I took at Cornell,

was Mammalogy, and not because of the course content, but because it was

there that I met Patty Morris, the love of my life.

“Hey, how ‘bout those bats?” Not the smoothest pick-up

line, but those were my first words to Patty outside of class, in

reference to the live bats exhibited in that morning’s class.

It must have worked because we’re still together!

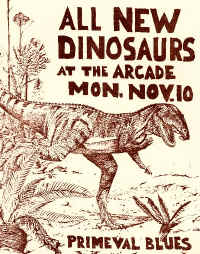

My Cornell years involved other pursuits, including Frisbee, the

Grateful Dead, and a series of bands in which I was lead guitar and

vocalist. One of these

bands was a blues band that took the name of a Bill Stout book, All

New Dinosaurs,

that happened to be sitting on my coffee table after a rehearsal; the

name seemed apt since we were putting a new spin on old blues tunes that

most folks thought were long extinct.

Patty and I were married in 1982 just after graduation, and we

remained the next year in Ithaca, just hanging out and having fun. |

|

In 1983 I started a masters degree program at the University of

Kansas in Lawrence, under the direction of Larry Martin.

KU was in something of a graduate school “golden age” at the

time, and I hesitate to list for fear of omission the many now renowned

people I associated with there in both VP, Herpetology, and elsewhere.

It was an exciting time, and much of my present philosophy and

work ethic I owe to the examples posed by those other KU grad students.

I also owe a huge debt to Larry Martin, who got me interested in

so many things. He always

encouraged me to look at modern animals along side extinct groups, and

this has emerged as my major research paradigm, these nascent ideas

later evolving into the extant phylogenetic bracket approach.

And of course it was Larry who introduced me to the previously

under-appreciated anatomical system of cephalic pneumaticity, which

became my major research focus for a decade and a half.

Although Larry and I are often now pitted as opponents in the

fierce debate on avian origins, he has been one of the most important

positive influences in my career. While

at KU, I learned a trade (at least that’s how I viewed it then),

namely that of teaching human gross anatomy.

I was a teaching assistant for six semesters during my four years

at KU. Despite the

wonderful training in comparative biology I was getting at Kansas, I was

convinced that it was human anatomy that was going to get me a job.

Thus, when it came time for shopping for a PhD program, I was

quite mercenary (and not a little cynical) in seeking only “big-name

East Coast schools” where I could enhance my human anatomy teaching

credentials. In retrospect,

it worked out well, but as an explicit plan it all seems quite

distasteful now. In 1983 I started a masters degree program at the University of

Kansas in Lawrence, under the direction of Larry Martin.

KU was in something of a graduate school “golden age” at the

time, and I hesitate to list for fear of omission the many now renowned

people I associated with there in both VP, Herpetology, and elsewhere.

It was an exciting time, and much of my present philosophy and

work ethic I owe to the examples posed by those other KU grad students.

I also owe a huge debt to Larry Martin, who got me interested in

so many things. He always

encouraged me to look at modern animals along side extinct groups, and

this has emerged as my major research paradigm, these nascent ideas

later evolving into the extant phylogenetic bracket approach.

And of course it was Larry who introduced me to the previously

under-appreciated anatomical system of cephalic pneumaticity, which

became my major research focus for a decade and a half.

Although Larry and I are often now pitted as opponents in the

fierce debate on avian origins, he has been one of the most important

positive influences in my career. While

at KU, I learned a trade (at least that’s how I viewed it then),

namely that of teaching human gross anatomy.

I was a teaching assistant for six semesters during my four years

at KU. Despite the

wonderful training in comparative biology I was getting at Kansas, I was

convinced that it was human anatomy that was going to get me a job.

Thus, when it came time for shopping for a PhD program, I was

quite mercenary (and not a little cynical) in seeking only “big-name

East Coast schools” where I could enhance my human anatomy teaching

credentials. In retrospect,

it worked out well, but as an explicit plan it all seems quite

distasteful now. |

| In 1987, we left Kansas for Baltimore and the

doctoral program at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. I left with those “credentials” I had sought, but I got

so much more along the way. Hopkins

Med School was a world away from the KU Museum.

It is very much a medical environment and located in an often

dangerous urban setting. At

the time, the Functional Anatomy and Evolution program was very young

and the course offerings consisted primarily of the first-year medical

curriculum. Although this seemed inappropriate to me at first, I quickly

saw that this background in medical physiology, histology, molecular

biology, and biochemistry greatly enhanced my marketable training, and

started me down the road to medical education that I continue today. But beyond that, it clearly made me a better evolutionary

biologist. It was at

Hopkins that I made the seemingly paradoxical observation that many of

the most sophisticated and rigorous paleontologists had medical gross

anatomy training and were located at med schools, not museums.

Although I was clearly plotting my job-hunting strategy, I gained

new perspectives and approaches at Hopkins.

Most influential was my PhD advisor and mentor Dave Weishampel,

who, in addition to an encyclopedic knowledge of dinosaurs, is

interested in the conceptual basis of his science.

For example, Dave introduced me to the conceptual framework

offered by the German school of Constructional Morphology.

He also showed me that dinosaur functional morphology could be

scientific, quantitative, and cutting-edge.

In fact, in general I came away from Hopkins with both training

in and a stronger appreciation for biomechanics, morphometrics, and

quantitative biology. I was

also able to participate in Dave’s field program in the St. Mary River

Formation of Montana—two wonderful seasons in the Late Cretaceous.

I would have liked to spend additional seasons, but then, as now,

my scientific questions have not been faunistic or requiring

paleontological fieldwork. My trips to Louisiana to work on alligators are more reflective of the

kind of field experiences I can justify now.

In general, my five years at Hopkins were a time to crank on

publications and my dissertation (I had a fellowship and hence minimal

teaching responsibilities), and to plan my future professional course. |

|

The professional years.—Having

spent nine years in graduate school, the thought of additional years of

postdoctoral training was not too enticing.

Thus, I directed my efforts at getting a job—an academic,

preferably tenure-track, assistant professorship.

Job hunting while finishing one’s doctoral dissertation is not

optimal for a variety of reasons, not least of which is that most search

committees want to see that that PhD is truly done and in hand.

Consequently, my initial applications were unsuccessful.

As they say, if you can’t be good, be lucky—and I got lucky.

The New York College of Osteopathic Medicine (NYCOM) on Long

Island had lost a faculty member at a late date and needed an anatomist.

Fortunately, a colleague from Hopkins, Nikos Solounias, was a new

faculty member at NYCOM, and alerted me to the position.

I had the “credentials, ” I had the teaching experience, and

I had the inside track (thanks to Nikos), and I got the job.

One little detail: I had to actually finish my dissertation on

time. The transition

(mid-August, 1992) was a blur: we moved to Long Island on a Saturday,

returned to Baltimore on Sunday, I defended my dissertation on

Wednesday, revised it on Thursday, turned it in on Friday, made the

final move to Long Island on Sunday, and started work at NYCOM at 9AM

Monday morning—oh, and Patty was five-months pregnant! The professional years.—Having

spent nine years in graduate school, the thought of additional years of

postdoctoral training was not too enticing.

Thus, I directed my efforts at getting a job—an academic,

preferably tenure-track, assistant professorship.

Job hunting while finishing one’s doctoral dissertation is not

optimal for a variety of reasons, not least of which is that most search

committees want to see that that PhD is truly done and in hand.

Consequently, my initial applications were unsuccessful.

As they say, if you can’t be good, be lucky—and I got lucky.

The New York College of Osteopathic Medicine (NYCOM) on Long

Island had lost a faculty member at a late date and needed an anatomist.

Fortunately, a colleague from Hopkins, Nikos Solounias, was a new

faculty member at NYCOM, and alerted me to the position.

I had the “credentials, ” I had the teaching experience, and

I had the inside track (thanks to Nikos), and I got the job.

One little detail: I had to actually finish my dissertation on

time. The transition

(mid-August, 1992) was a blur: we moved to Long Island on a Saturday,

returned to Baltimore on Sunday, I defended my dissertation on

Wednesday, revised it on Thursday, turned it in on Friday, made the

final move to Long Island on Sunday, and started work at NYCOM at 9AM

Monday morning—oh, and Patty was five-months pregnant! |

| I spent three very important years at NYCOM—important

in that they very much changed my sense of my career. Although I always regarded my NYCOM position as short-term, I nonetheless embraced the job and became involved and

interested in medical education. At

NYCOM I discovered the business of academia.

Being a professor, I found, is much more than research and

teaching. I quickly learned

the requisite skills of departmental politics, memo-writing, wrangling

about space, staffing, purchasing, and all sorts of other tasks that I

never envisioned doing in my ivory tower of Academe.

At NYCOM, I more-or-less grew up, professionally speaking.

Still, there was ample research time, and I was able to crank on

various projects for months at a time.

NYCOM is very well positioned geographically, being less than an

hour from New York City (and the American

Museum of Natural History where I was made a Research Associate)

and is more or less equidistant from Boston and Washington, DC; thus,

most of the best natural history collections in North America were

within a four-hour radius. But

the real joy of NYCOM was my colleagues, in particular my old friend

Nikos and, later, Scott Sampson and Des Maxwell, with all of whom I

still work closely. Scott

and Des have both since left NYCOM.

In particular, Scott and I developed a research partnership that

will continue to bear fruit well into the foreseeable future.

More importantly perhaps, Scott has become one of my closest

friends and most trusted colleagues. |

| For Patty and me, our Long Island years are

especially treasured in that it was on “The Island” that our son Sam

was born in 1993. We loved

the beaches, the parks, and the libraries, and we will always have fond

memories of taking Sam to those places.

But we never truly felt at home on Long Island, and the cost of

living was simply too high for a family living on a college

professor’s wages. Thus,

I interviewed for other academic positions every year I was at NYCOM. |

In 1995, I accepted an offer from the

Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine (OU-HCOM) to join

the faculty and become a player in a ground-breaking new

curricular track, the PCC (a Patient-Centered Continuum). The

PCC, just a year old when I arrived, is a problem-based learning

curriculum revolving around real clinical cases.

My role has been to coordinate the anatomical experiences for the

PCC students. OU-HCOM

is one of the most innovative and ambitious places I’ve heard

of, let alone worked in. Consequently, it’s a truly exciting environment, and I’m

surrounded by competent and committed people.

Since 1997, I’ve expanded my educational mission out past

medical school to the residency years, and I coordinate basic

science education for the General Surgery and Pediatric

residency programs for the consortium of osteopathic hospitals

in the state of Ohio.

This strong emphasis in medical education would seem to contrast

sharply with a research program in the evolutionary biology of

dinosaurs and other vertebrates…and it does—big time.

My hospital-based medical colleagues have no inkling of my

paleontological research unless they happen to see something

about me in the newspaper. Likewise,

my scientific colleagues are usually aghast when they hear of

the extent of my involvement in medical education.

It somehow works for me. I’m

certainly never bored. In 1995, I accepted an offer from the

Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine (OU-HCOM) to join

the faculty and become a player in a ground-breaking new

curricular track, the PCC (a Patient-Centered Continuum). The

PCC, just a year old when I arrived, is a problem-based learning

curriculum revolving around real clinical cases.

My role has been to coordinate the anatomical experiences for the

PCC students. OU-HCOM

is one of the most innovative and ambitious places I’ve heard

of, let alone worked in. Consequently, it’s a truly exciting environment, and I’m

surrounded by competent and committed people.

Since 1997, I’ve expanded my educational mission out past

medical school to the residency years, and I coordinate basic

science education for the General Surgery and Pediatric

residency programs for the consortium of osteopathic hospitals

in the state of Ohio.

This strong emphasis in medical education would seem to contrast

sharply with a research program in the evolutionary biology of

dinosaurs and other vertebrates…and it does—big time.

My hospital-based medical colleagues have no inkling of my

paleontological research unless they happen to see something

about me in the newspaper. Likewise,

my scientific colleagues are usually aghast when they hear of

the extent of my involvement in medical education.

It somehow works for me. I’m

certainly never bored. |

| Apart from the challenges and rewards of medical

education, I’m part of a thriving program in Ecology and Evolutionary

Biology with a large group of motivated young faculty that are bringing

acclaim to themselves, the EEB program, and Ohio University.

In particular, our evolutionary functional morphology group has

really gelled in recent years. The

core of this group consists of Audrone Biknevicius (an old friend from

Hopkins when we were grad students together), Steve Reilly, Pat

O'Connor, Susan Williams, Nancy Stevens, and our

collective students.

We have developed a productive synergy borne of frequent and

friendly interaction and collaboration.

Graduate students have become a

major part of my academic life, and my lab is rarely a quiet place. The

various research projects in the lab have expanded into many fascinating areas involving many different people.

Many days I feel more like a project administrator than a

scientist, trying to keep all the varied facets of the larger project

supplied, funded, and moving forward. |

|

Postscript.—When I was six years

old I wanted to be a professional paleontologist.

Of course, when I was seven I wanted to be a snowman, but, other

than that brief detour, my course has been fairly unwavering.

(Okay, there was that musician thing in college, but that was

about as likely as the snowman career.)

I always had a passion for science and found a way to make a

living of it. Some days I

think, “What a scam! They

actually pay me to do this stuff!”

Other days, mired in the banality of answering emails and

shuffling papers, I look wistfully out to the lab where my students are

gleefully lost in the joy of scientific discovery.

I realize that, in a sense, the occasional tedium of academia is

the “cost of doing business” for those exciting moments of

inspiration and insight. But,

moreover, the other parts of the job carry their own rewards.

In particular, teaching future physicians has emerged as one of

the most satisfying parts of my job.

And even the administration and committee work impart a sense of

service and of being a part of a larger mission.

Along the road to this professional career, many people have

helped me, inspired me, supported me, and set me straight.

Many of them are acknowledged here.

Of these, my parents—Mel and Barbara Witmer—and my wife Patty

have been my staunch supporters as well the role models for my

professional (and personal) conduct. To them, and to my son Sam, I dedicate my future career. Postscript.—When I was six years

old I wanted to be a professional paleontologist.

Of course, when I was seven I wanted to be a snowman, but, other

than that brief detour, my course has been fairly unwavering.

(Okay, there was that musician thing in college, but that was

about as likely as the snowman career.)

I always had a passion for science and found a way to make a

living of it. Some days I

think, “What a scam! They

actually pay me to do this stuff!”

Other days, mired in the banality of answering emails and

shuffling papers, I look wistfully out to the lab where my students are

gleefully lost in the joy of scientific discovery.

I realize that, in a sense, the occasional tedium of academia is

the “cost of doing business” for those exciting moments of

inspiration and insight. But,

moreover, the other parts of the job carry their own rewards.

In particular, teaching future physicians has emerged as one of

the most satisfying parts of my job.

And even the administration and committee work impart a sense of

service and of being a part of a larger mission.

Along the road to this professional career, many people have

helped me, inspired me, supported me, and set me straight.

Many of them are acknowledged here.

Of these, my parents—Mel and Barbara Witmer—and my wife Patty

have been my staunch supporters as well the role models for my

professional (and personal) conduct. To them, and to my son Sam, I dedicate my future career. |

|

|

|

|