By Maia LeClair, Journalism ‘26, and Maggie Malone, Journalism ‘26 for JOUR 4130 Gender, Race, and Class in Journalism with Victoria LaPoe, Spring 2025

During the spring 2025 semester, the staff of the Mahn Center for Archives and Special Collections worked intensively with Victoria La Poe’s JOUR 4130 class, Gender, Race, and Class in Journalism and Mass Media. The students explored, selected, and researched materials from the collections, then worked in small groups to prepare presentations. The students had the option to then expand their research into a blog post like this one for their final project.

The 1930 Millfield Mine Disaster of Athens County stands as “the worst coal-mining disaster in Ohio history,” according to author and geologist Douglas L. Crowell. The disaster is a poignant reminder of the dangerous working conditions, exploitation, and systemic neglect faced by laborers in the early 20th century. The tragedy brought to light the complex socio-political forces surrounding the mining industry, labor movements, and how the news media framed mining-related disasters at the time.

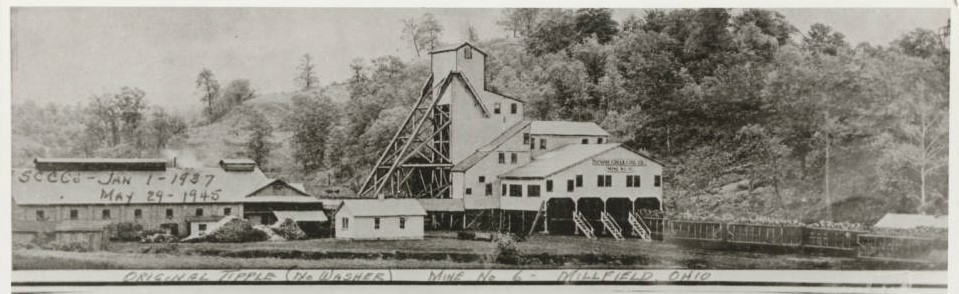

Image of the Sunday Creek Coal Co. Mine No. 6 in Millfield, Ohio, circa 1937-1945 (Ohio University Digital Archives).

Origins of the Disaster

Coal mining, particularly in the Appalachian region, posed serious danger for workers. The miners who worked in the Millfield Mine were predominantly men, many of whom came from working-class backgrounds and were subject to intense exploitation by the mine owners. According to Jim Branscome in the essay “Annihilating the Hillbilly: The Appalachians’ struggle with America’s institutions” unsafe conditions were perpetuated until 1969 when the Mine Health and Safety act was finally passed nationally after the deaths of 78 coal miners in Farmington, West Virginia. Before that, the conditions in the mines were grim. Poorly ventilated shafts, outdated equipment, and lax safety regulations led to a high rate of accidents, including the catastrophic explosion at Sunday Creek Coal Company Mine that claimed the lives of 82 men on November 5, 1930.

The town of Millfield itself was centered around the mine’s economy, exclusively relying on the Millfield mine for all general necessities. It had a general store, a company store and a post office. Nearly everyone worked in the mine.

On the day of the disaster, the company’s top executives such as William Tytus, the president of the Sunday Creek Coal Company, were inspecting new safety equipment. They, too, were killed in the explosion. Later, nineteen people were rescued two miles away from the initial blast about ten hours after the explosion. Overall, the disaster attracted immense amounts of press coverage, including local and national.

The company did little to protect the coal miners, which was found after investigations were completed of the mine. In reference to the powers at play at the Sunday Creek Coal Company Mine, author of “The Millfield Mine Disaster” and historian Ron Luce said in an Athens News article,

I think there’s abundant evidence that shows there was a clear lack of commitment to miner safety. … The owners only owned it for not quite a year when the explosion happened. So they opened it up, knowing it was a gassy mine, knowing they had incorrect equipment, that it was dangerous…

Reporting Shortfalls

Local newspapers only reported some of these findings. Headlines and stories about the lives lost in the explosion filled the front page of the November 7, 1930 issue of The Green and White, Ohio University’s student newspaper at the time. The explosion had occurred two days before publication. The featured stories include dramatic firsthand accounts of the event, such as “Frantic Miner Halts Car to Tell Youth of Disaster; Wives and Mothers Cry Distress At Scene of Explosion” and “Relatives of Students Are Disaster Victims.”

As a whole, reporters were telling local stories about the workers, miners, miners’ families and the volunteers. There was very little official information circulating at the time, due to people not willing to go on record before the investigations were completed. Regarding newspaper coverage of the disaster and according to Athens News, Luce said,

If you read any of the newspapers from that period of time, they’re so inaccurate and they’re wild — sometimes just claiming things that never happened, claiming people attached to other people who aren’t.

This resulted in often inaccurate and contradictory information from journalists. There was only one formal statement given to the press from the Bureau of Mines, according to Ron Luce’s book “The Millfield Mine Disaster.” It included statements on what aspects the mine failed in relating to safety. One specific point in the brief, however, stated how there was “nothing is said as to negligence by anyone.” Even still, this brief decidedly put the blame for the explosion on the miners and their open flame lights, which could be dangerous (Ron Luce, 109). The company and its executives, being the dominant power structure, set the narrative, which the press used and perpetrated.

When news of the Millfield Mine Disaster reached the public, media outlets often relied on sensationalism, portraying the incident in ways that reinforced preconceived notions about the region and its people. National news sources, especially those with no ties to Appalachia, frequently leaned on stereotypes to heighten the drama. One example, from the Zanesville Signal, described a woman waiting on her sons and husband to be found as a “brave little wife.” Gender played a significant role in this portrayal, as society viewed women as helpless during such disasters. At the time, only men worked in the mines. Women weren’t allowed underground, so none died in the tragedy. The media cast women as nursemaids and homesteaders, reinforcing the patriarchal ideal of the male head of household that dominated Appalachian mining communities in the 1930s.

Priming and framing played significant roles in how the disaster was presented to the public. Journalists focused on the spectacle of the disaster, rather than examining the deeper causes, such as corporate negligence, the lack of regulatory oversight, or the exploitation of labor. Even Elmer Dingeldey’s widely circulated personal account, while deeply emotional and graphic, ultimately reinforced this focus on tragedy and trauma rather than systemic accountability.

As editor of The Green Goat, Dingeldey joined the rescue efforts and later documented his harrowing experience in a piece titled “Graphic Description of Scene Following Ohio’s Worst Mine Disaster at Millfield, November 5,” which was prominently featured as the opening story in 1930 issue of The Ohio Alumnus as well as in The Green and White.

Priming, the process by which media coverage sets the stage for how people think about an issue, played a key role in shaping how the Millfield Mine Disaster was perceived. Dingeldey’s account, like many other reports, primed readers to focus on the emotional devastation of the event. His vivid descriptions set the tone for how the public understood the disaster.

His writing is visceral: “As I assisted in raising the lifeless forms of 75 miners… as I climbed through the narrow, smelly underground lanes to help in the rescue work, I realized that all that I had ever known about death was trifling” (Dingeldey 1930, para. 1).

Rather than framing the mine explosion as part of a larger pattern of unsafe working conditions or corporate negligence, the media primed audiences to react emotionally, emphasizing the immediate human tragedy. By focusing on the physical horrors and the personal experiences of rescuers, Dingeldey’s narrative reinforced the idea of the disaster as a tragic, isolated event rather than part of a larger, systemic issue within the mining industry.

Framing (OHIO login required), the way a story is structured and the angle it takes, further amplified this focus on spectacle. Dingeldey’s graphic and personal descriptions of the aftermath, such as the image of “one young chap…found huddled with an overall strap clenched viciously in his right hand” or “an old, grizzled veteran…found dead on bended knees, reclining against the wall of coal, with his hands folded in attempted prayer” (Dingeldey 1930, para. 5). These lines aim to elicit a strong emotional response from the reader.

While powerful, these descriptions center on the physical aftermath and personal suffering, rather than on the systemic issues that contributed to the disaster. This framing effectively turned the story into a spectacle, drawing attention to individual tragedy and transformation rather than exploring the negligence of the coal company or the dangerous working conditions that miners faced on a daily basis. In this way, the framing of Dingeldey’s piece aligned with broader media patterns that sensationalized human suffering without challenging the status quo or questioning the institutional failures that led to the disaster.

Shifting Narrative

In other press coverages, such as from The Post from years later, this way of writing about the event continues to abound. However, the narrative is slowly changing. The efforts of the miners, who honored the day of the event yearly, helped erect the plaque that still stands at the site. There is some press coverage, from The Post, about the commemorations, which includes interviews from the remaining miners. Other efforts to speak to Appalachian culture and history include interviews from the play “The Other Half Speaks,” produced in part by Ohio University professor Helen Horn. Many of the women interviewed were wives or daughters of miners who died that day. Their personal accounts show another side to the stories of living in a coal town. Joanne Prisley, director of the Athens County Historical Society, said,

When men went into the mines, women did everything they could to make life livable on the surface.

Amidst the Millfield Mine Disaster aftermath, there was little mention of mine safety conditions, labor practices, or the responsibilities of the Sunday Creek Coal Company. Instead, the emphasis remained on the emotional and dramatic aspects of the scene, images of soot-covered bodies, overwhelmed rescuers, and the haunting quiet of the mine. In this way, even seemingly authentic, eyewitness reporting contributed to a depoliticized understanding of the event, aligning with broader patterns of media framing that prioritized human interest over critical analysis.

Present-day Implications

Today, the only remaining evidence of the mine disaster is the smokestack which stands on the site. The environmental damage of the disaster is immense, as much of the rubble is still there, and the mine is closed off to visitors, presumably due to safety reasons. Mines, while operating, affect the surrounding environment negatively, and even closed mines still leak unsafe gases. Even after more than eighty years since the disaster, its ramifications are still great and are still present.

Overall, what we can learn from this disaster is to recognize our own preconceived biases. The press coverage for the disaster was sensationalized and, again, included many stereotypes. It is important to critique these stereotypes and avoid using them when covering an event such as this. The Millfield Mine Disaster continues to be one of the worst mine disasters, but the way the public can perceive it and remember it, ninety-five years later, doesn’t have to be the same.

References

Crowell, D. L. (1995). History of the Coal-mining Industry in Ohio.

Branscome, J. G. (1970). ANNIHILATING THE HILLBILLY: The Appalachian’s struggle with American institutions. In Annihilating The Hillbilly. Collection of Appalachian Movement Press Publications. https://media.library.ohio.edu/digital/collection/speccoll/id/2050/rec/103 (Original work published 1970)

Collection on “The Other Half Speaks,” MSS180, Ohio University Libraries, Athens, Ohio. https://archivesspace.ohio.edu/repositories/2/resources/775

Executives of East Fultonham and Philo Plants on Inspection Tour as Disaster Occurred. (1930, November 6). Zanesville Signal. https://usminedisasters.miningquiz.com/saxsewell/1930_Millfield_No_6_Mine_explosion_NEWS6.pdf

Green Goat | Ohio University. (n.d.). https://www.ohio.edu/library/collections/archives-special-collections/university-archives/green-goat

Luce, Ron. The Millfield Mine Disaster. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2024.

Media Culture and the Triumph of the Spectacle by Douglas Kellner. (n.d.). https://pages.gseis.ucla.edu/faculty/kellner/papers/medculturespectacle.html

Miles Layton. (2024, February 13). Local historian searches for the truth about Millfield Mine tragedy. The Athens NEWS. https://www.athensnews.com/news/local-historian-searches-for-the-truth-about-millfield-mine-tragedy/article_9b3412ec-ca76-11ee-b57d-3721b8483f4b.html

Millfield, Ohio. (n.d.). https://www.ohgen.net/ohathens/millfield

Millfield Tragedy Revisited. (1995, August). Ohio Geology. https://web.archive.org/web/20100203180432/https://www.dnr.state.oh.us/Portals/10/pdf/newsletter/Fall95.pdf

Millfield Mine Disaster Recalled. (1976, November 8). The Post. https://media.library.ohio.edu/digital/collection/studentnewspapers/id/47422/rec/7

Millfield: Memories of a Mine. (1975, February 12). The Post. https://media.library.ohio.edu/digital/collection/studentnewspapers/id/52134/rec/5

Scheufele, D. A. (n.d.). Framing as a theory of media effects. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ583536

Two Residents Relive Mining Days. (1990, October 26). The Post. https://media.library.ohio.edu/digital/collection/studentnewspapers/id/61112/rec/2

Zamith, R. (n.d.). Priming Theory :: The International Journalism Handbook. https://ijh.rodrigozamith.com/media-effects/priming-theory/

18 are saved in explosion at Millfield. (1930, November 6). The Salem News. https://usminedisasters.miningquiz.com/saxsewell/1930_Millfield_No_6_Mine_explosion_NEWS2.pdf