Claudia Fuller ’27, English (Creative Writing), spring 2025 Mahn Center Intern

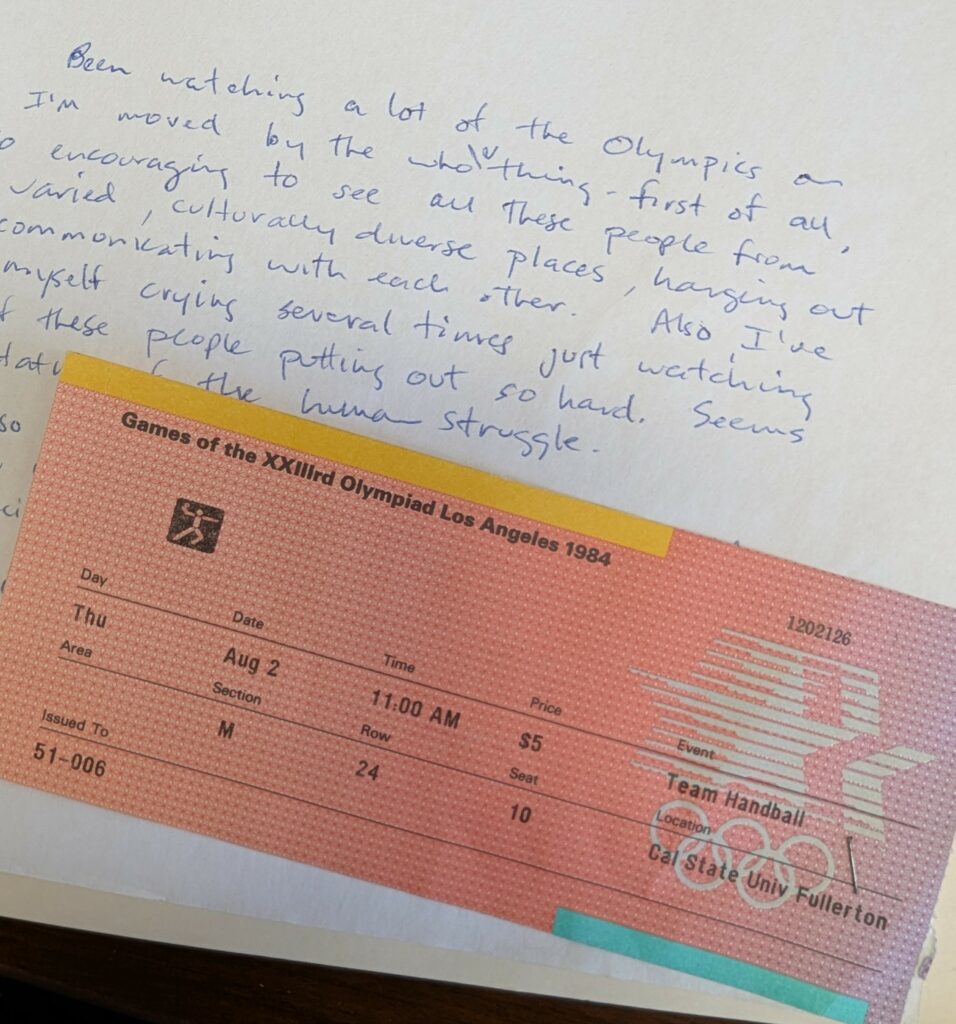

When I began my internship at the Mahn Center, I was nervous. With any new role, this is to be expected, but as spring semester inched closer, I became convinced I wasn’t ready. I applied for the internship because I have an interest in personal narratives; in the stories of those around us, tucked into attic chests and hidden between pages. My interest grew semi-organically, cultivated in my father’s antique shop in rural Ohio. Though my father’s specialty is signs, glassware, and oddities, I was often exposed to ephemera—that is, things not made to last or be preserved. These items—fliers, ticket stubs, menus, bingo cards, programs, newspapers and paper dolls—were usually discarded and left to disintegrate. For this reason, they are of value to collectors, and to antiquers like my father.

Despite this exposure, however, I understood that my knowledge of archiving was limited. In my father’s shop, we were always careful with the objects and materials we were handling, but there was no need to think critically about what I was looking at. I knew how to work with spreadsheets, but I was used to jotting what we needed in various notebooks and legal pads (often leading to disorganization.) I knew how to assess the age of a document, but not its content. Outside of the processing room, these materials were just that—objects, removed from their personal histories.

It is not unheard of for writers to demand the destruction of their work upon death; Kafka famously asked his friend Max Brod to burn his unpublished manuscripts. However, some writers have an interest in preservation; some simply wish to leave a legacy behind. Whatever the reason, it occasionally happens that a writer might contribute a lifetime of written work to an academic institution. At Ohio University, the Mahn Center is home to the collections of multiple poets, whose personal papers and written legacies are stored there. Upon beginning my internship this spring, I was assigned the James Bertolino poetry collection.

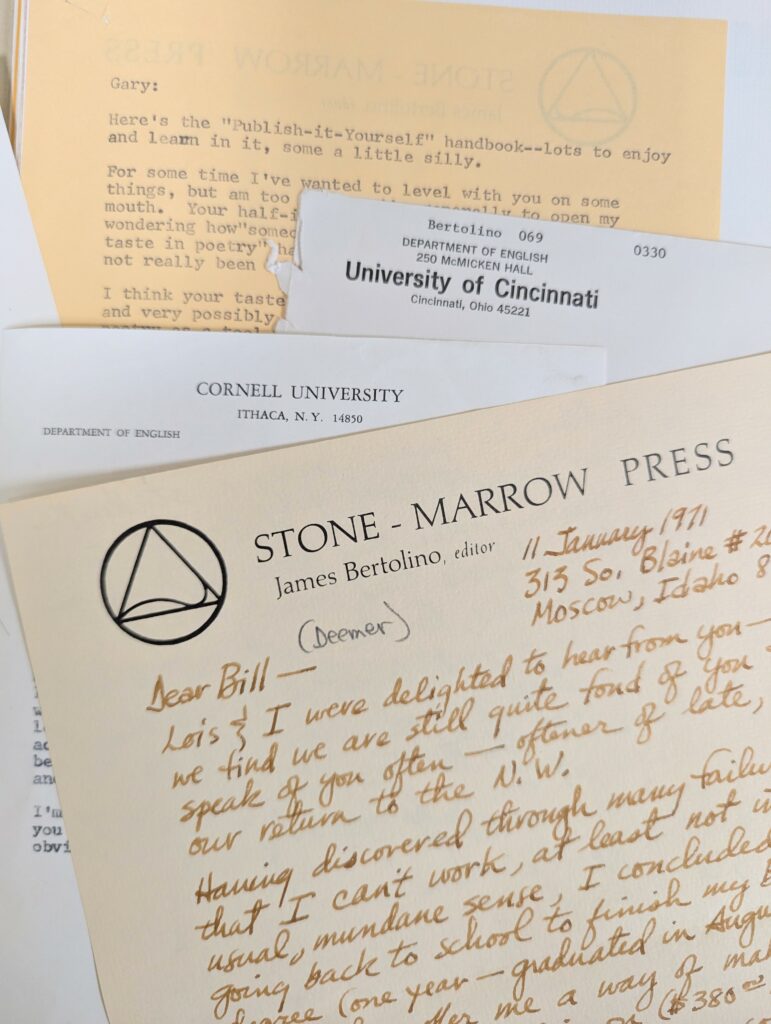

James Bertolino was born in Pence, Wisconsin in 1942. Bertolino taught at several universities, including the University of Cincinnati and the University of Washington. Having lived in Ohio for several years, Bertolino felt that his work should be housed here. His collection contains over two thousand letters and a thousand poems, written between the early 1960s and the late 2010s.

During the beginning of my internship, I pored over Bertolino’s letters (ie: correspondence.) These were from other writers, most of them writers from the Midwest. As a Creative Writing major, I was (and to some extent, still am) a little embarrassed that I didn’t recognize a large majority of them. Prior to starting the internship, I’d never read Douglas Blazek, Lyn Lifshin, Robert Bly, Anne Waldman, or Clayton Eshleman; now I can say I’ve read their work and their letters. (As a side note, I am proud to admit I recognized Gwendolyn Brooks and Ursula K. Le Guin. And, as a plus, I got to brag to my best friend that I handled a signed note from the author of the Earthsea books.)

As I leafed through Bertolino’s letters, I realized something: these writers were not isolated from one another. What I mean by this is that Bertolino was one part of a large coast-to-coast community of writers. Many of these artists—most of them poets—who were writing to Bertolino were also writing to each other. I find this particularly fascinating as these letters date back to the early sixties, when “snail mail” was simply mail. Though Bertolino corresponded with several writers over a number of years, letters were often few and far between. Without social media, the ability to stay in constant contact is lost. This is why I find Bertolino’s circle so remarkable; in an era before social networking sites and forums, a group of writers were able to foster a community.

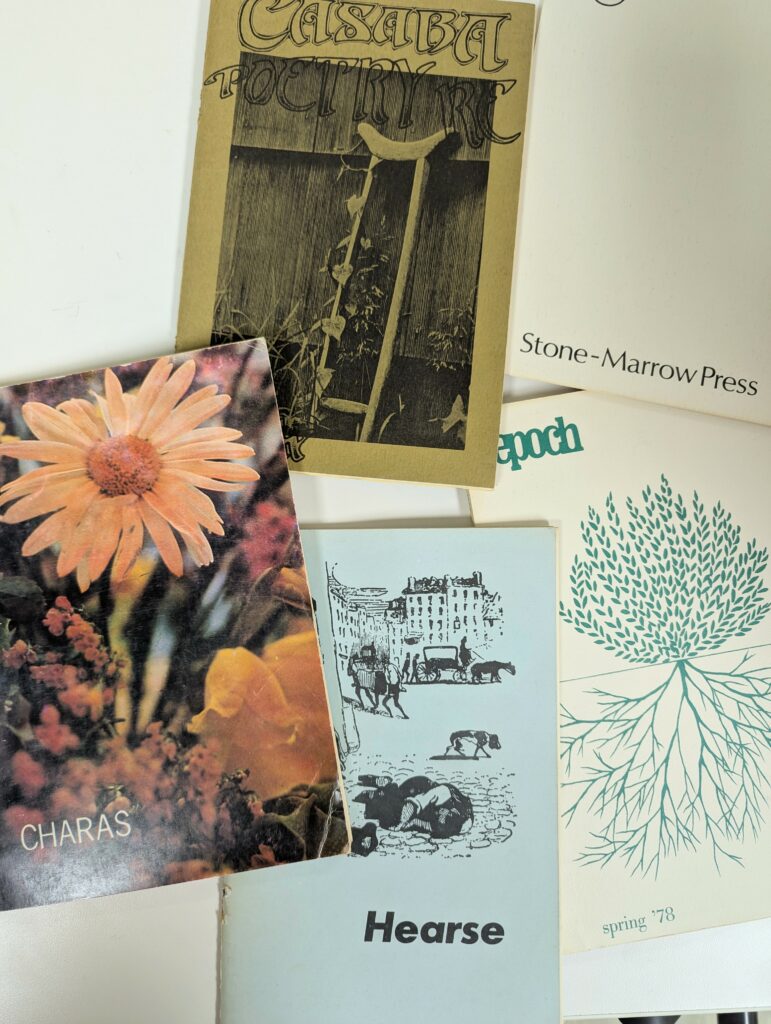

During the 1960s and 70s, small presses experienced a golden age. This period is often referred to as the “Mimeo Revolution.” While not a new invention, the mimeograph’s accessibility gave artists the freedom to distribute their work on a wider scale. Marginalized writers, who struggled to gain attention from traditional avenues, also found success through independent publications. Unlike the mainstream press, small presses were run by fellow poets and writers with a genuine interest in the craft. They were not in it for fame or glamour, but for the love of writing.

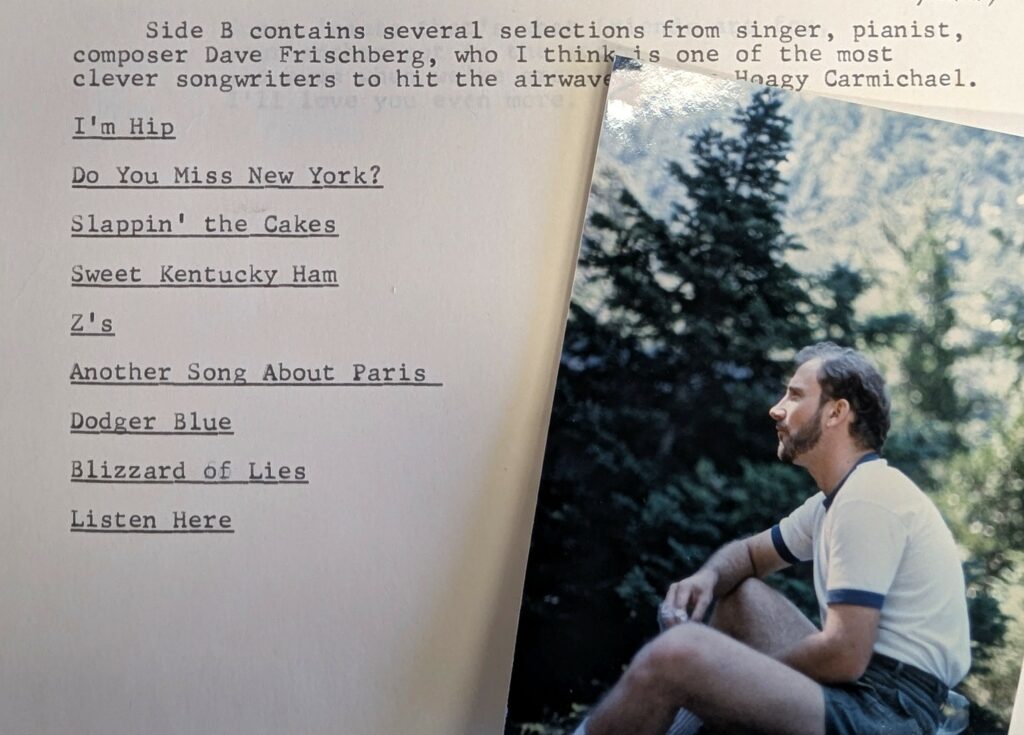

Throughout his career, Bertolino has maintained a deep admiration for small presses, even founding his own in 1972, Stone Marrow. He frequently sent in poems to friends in need of pieces for their own journals, who in return sent him their own. The often reciprocal nature of his correspondence necessitated collaboration. Having dedicated myself to writing for the past seven years, I am aware many people consider it to be a solitary excursion. But the truth is that writing demands collaboration; it demands community.

The work produced during the Mimeo period was not meant to last. Printed materials were produced as quickly and cheaply as possible and weren’t liable to be preserved. Archives, then, are valuable repositories for the ephemeral. They are also home to lifetimes of personal histories—including James Bertolino’s. Without archives like the Mahn Center, these histories could easily be erased. I understand why ephemera is valuable to collectors, but I think the far richer reward lies in learning the narratives they tell.

Further Exploring:

James Bertolino papers collection description

#JamesBertolinopapers on Instagram

The Mahn Center for Archives and Special Collections is open by appointment only, please contact us with questions or to make an appointment.